01: Put on the Whole Armor of God

This is a spiritual battle. I do not mean that metaphorically.

01: Put on the Whole Armor of God

NOTE: you can listen to this episode using the embedded player above, or for free on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts. You can also access the full copy of the essay version below, as well as all future texts, at timezeropod.com.

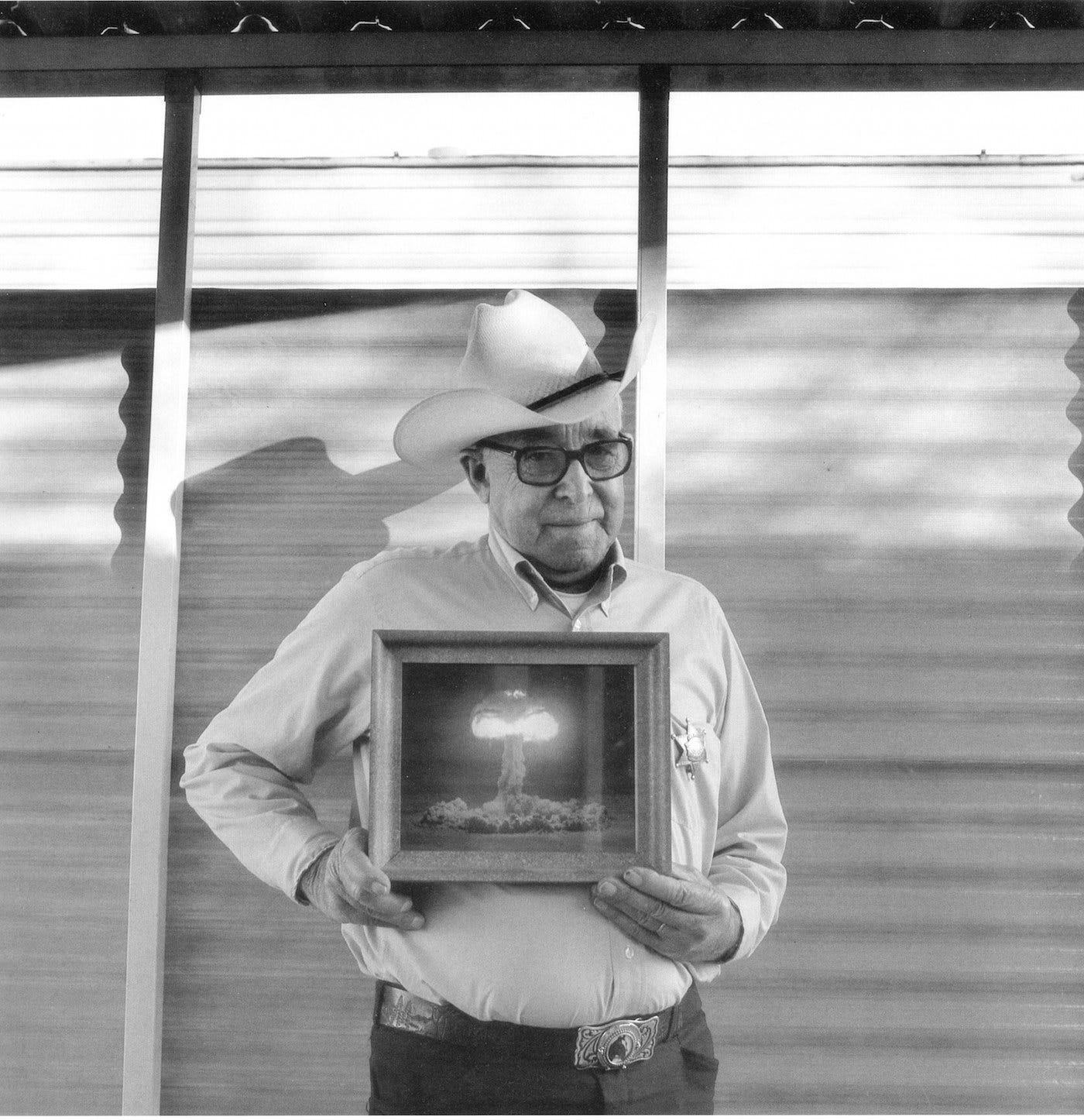

Robert Del Tredici, Yellow Brick Road, 1979.

In the black-and-white photograph, a middle-aged woman and two children walk a small dog down a quiet, tree-lined street. It’s a suburban neighborhood: split-level homes with grass-covered yards. Asphalt driveways. No sidewalks.

This could be almost anywhere in Middle America, so the name suits: Middletown, a borough of less than 10,000 inhabitants along the Susquehanna River in Pennsylvania, right south of Harrisburg, and a couple hours west of Philly.

Just beyond the neighborhood, towering above the tree line, are two massive concrete hyperboloid cooling towers, like the ones that loom ominously over the town of Springfield on The Simpsons.

Canadian photographer Robert Del Tredici captured this image, which he titled Yellow Brick Road, on July 20, 1979, technically just outside of Middletown.

Less than three months earlier, reactor unit two at the Three Mile Island Nuclear Generating Station—the site of those colossal cement cylinders—partially melted down. Three Mile Island sits just 2,000 feet, not even half a mile, from the neighborhood in Del Tredici’s photograph.

On a CBS broadcast on the evening of March 28, 1979, Gary Shepard reported:

At about four o’clock this morning, two water pumps that help cool reactor number two shut down. Officials say some 50,000 to 60,000 gallons of radioactive water escaped into the reactor building and that the radioactivity penetrated the plants walls. Steam escaped into the atmosphere and radiation was detected as far as a mile away.1

Thirty-four years and four days before Del Tredici shot his Yellow Brick Road photograph, the United States detonated the world’s first nuclear weapon, a highly secretive plutonium implosion device, codenamed Trinity, in the stunning Tularosa Basin of central-southern New Mexico.

Three weeks later in Japan, in the waning hours of World War II, they detonated nuclear weapons over Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The blasts, fires, and radiation from those weapons would ultimately kill at least a quarter million people2, mostly civilians. These remain the only two uses of nuclear weapons in warfare.

The nonpartisan Arms Control Association lists 2,056 nuclear weapons detonations since Trinity in 19453. Calling these “tests” feels, at best, intellectually dishonest. None of them were simulations, by any measure. They were literal nuclear bombs, exploded on actual landscapes in Nevada, the Marshall Islands, Kazakhstan, Algeria, South Australia, and French Polynesia, among other places, all of which are populated by plants, animals, and people.

In 2003, Japanese artist Isao Hashimoto produced a hypnotic, simple, and disturbing animated video, 1945-1998, that shows the location of each of these blasts.

The United States is responsible for more than half of those detonations—1,054, by our own official numbers. Between 1946 and 1958, the US military set off 67 nuclear weapons in the Enewetak and Bikini atolls in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, vaporizing land masses and destroying the homes of Marshallese people.

Between 1951 and 1992, just 65 miles north of Las Vegas at the Nevada Test Site, they detonated more than 900 additional nuclear weapons, most of which were several times more powerful than the bombs exploded over Japan. One hundred of those tests were atmospheric, meaning they were set off above the ground with absolutely zero containment strategies for radioactive fallout—except attempting to predict desert wind patterns.

Over a forty-year span, the US military detonated, on average, a nuclear bomb every two weeks at the Nevada Test Site. I was already in the fifth grade by the time they stopped.

Nevada is, in fact, the most nuked place on Planet Earth.

Physicists and military personnel called the precise moment that the weapons detonated zero time, or time zero, as in 3, 2, 1…

You’ve probably already heard about Three Mile Island, or at least heard the name.

The meltdown of unit two reactor on March 28, 1979, released radioactive gases and iodine into the environment and atmosphere, exposing an an estimated two million people to radiation4 (including, presumably, Del Tredici’s posse, and their little dog, too, who saunter so casually towards a still very radioactive Oz).

Cleanup efforts at Three Mile Island would take more than a decade, and end up costing over $1B5 (an amount equivalent to roughly $2B today). The health costs, however, have been less objectively quantifiable. Some epidemiological studies have determined that the rates of cancer in the area are higher to a degree that is statistically significant; other studies have not.

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission, an independent agency created by Congress in 1974 to “ensure the safe use of radioactive materials for beneficial civilian purposes while protecting people and the environment,” maintains that the Three Mile Island meltdown exposed those two million Pennsylvanians to an “average dose” of radiation6.

That causality between nuclear radiation and cancer, among other health impacts, is difficult to prove will become a frustratingly familiar refrain as we unpack nuclear histories.

The accident at Three Mile Island did lead to a major slowdown in the atomic energy sector, though reactor unit one—the one that didn’t melt down—was back online by 1985, and operated into 2019, at which time it was finally closed due to economic losses.

But by late 2024, Three Mile Island had returned to the headlines when Microsoft announced plans to reopen the plant’s unit one reactor to support the computer giant’s power-hungry artificial intelligence data centers. Amazon and Google are also pursuing nuclear power for their own AI systems.

In January, I spoke with Santa Fe-based photographer and activist Shayla Blatchford, who articulated a glaring blind spot in press coverage about the imminent “nuclear renaissance.”

“A lot of articles that are coming up are about nuclear power—how it’s the way forward and how green and clean it is. But they never mention the first half of the process: the mining. They never mention where remediation fits in. So here’s this whole part of it that’s damaging the land, and a culture, and communities, and they mention none of that.”

Blatchford is the founder of the Anti-Uranium Mapping Project, an interactive online archive documenting the impacts of uranium mining on the Navajo Nation. This year, the project was awarded a Creative Capital Grant.

“I would hope that people would be able to just find a way to consider: how do you clean up your mess before you get to play with all of your new toys related to atomic power?”

Beyond the way that these corporations have obfuscated the source of the materials required to power nuclear energy, not a single one of them has articulated any plan whatsoever for what to do with the colossal amount of nuclear waste—what many activists and critics call “forever waste”—that these purportedly green and clean plants are going to produce.

In fall 2021, several works by Yellow Brick Road photographer Robert Del Tredici were included in Devour the Land: War and American Landscape Photography since 1970, an exhibition at Harvard Art Museums.

Curator Makeda Best interviewed Del Tredici in a virtual event streamed that November. The photographer recalled his entry into the world of nuclear image-making.

“My first nuclear… adventure was to document the accident at Three Mile Island in southeastern Pennsylvania which, it turns out, was a very serious accident—an actual meltdown.”

Del Tredici pointed to the way that communities directly impacted by radioactive events are often dismissed by government, military, and industry officials.

“All the people who were saying they had rashes, they had miscarriages, their animals were dying, there were holes in trees, and they tasted metal in their mouths, all these things were simply dismissed. Because they didn’t want to believe that. But, about four years later, at Three Mile Island, they got a probe into the crippled reactor and, sure enough, it was a meltdown. About 45% of the core had melted. When you have a melt like that, you can calculate the gases that will escape. And the calculation was that an enormous amount of gas had escaped, and these things that the people were saying were true. They weren’t what the industry called radiophobia.

‘These people were just spooked.’

No. They were actual results.”

In the early 1980s, Del Tredici visited Hiroshima and Nagasaki, speaking in depth with survivors to explore what he called the “human meaning” of the bomb7. These visits inspired him to photograph US factories producing hydrogen bomb components, which were assembled in Amarillo, Texas. Many of these images appeared in his 1987 book, At Work in the Fields of the Bomb.

That same year, Del Tredici co-founded the Atomic Photographers Guild with Carole Gallagher and Harris Fogel, an international collective “dedicated to making visible all facets of the nuclear age.” Their archive includes Berlyn Brixner’s high-speed images of the Trinity Test, Kenji Higuchi’s documentation of Japanese workers cleaning up nuclear accidents, Nancy Floyd’s intimate portraits of US nuclear workers, and Yoshito Matsushige’s rare photographs of Hiroshima’s immediate aftermath.

Guild co-founder Carole Gallagher’s 1993 book, American Ground Zero: The Secret Nuclear War, documented communities in the Intermountain West affected by radioactive fallout from that decade-plus of atmospheric detonations at the Nevada Test Site. Her portraits and interviews reveal that, for many, the Cold War was actively hot. Radioactive fallout devastated towns, ranches, and water sources across Nevada and Utah, leaving lasting scars and, frequently, cutting lives short.

In the contemporary art world, the phrase “making visible the invisible” is used with eye-roll-inducing frequency. But when it comes to the nuclear—from the imperceptible but lethal qualities of radiation, to the geographically hidden military-industrial infrastructures that produce weapons of mass destruction—making visible the invisible is imperative to the survival of the human species. And the Atomic Photographers Guild knows this.

Carole Gallagher’s revelations come in the form of heartbreaking portraits of Americans dying of exposure-related cancers, courtesy of their own government.

Guild member Abbey Hepner, herself the descendant of Utah downwinders, and somebody that we’ll hear more from on Time Zero, has photographed every unassuming site in the Western United States that ships radioactive waste to the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant, an underground—thus very out-of-sight—nuclear waste storage facility outside of Carlsbad, New Mexico. Hepner prints the photos as uranotypes—a radioactive image-making process involving uranium.

In Del Tredici’s Yellow Brick Road, the visible, suburbia, collides with the invisible, radiation. The result is a truly dissonant American moment, one where domestic dreams and apocalyptic nightmares occupy the same space—physically, but also psychologically.

As locals around Three Mile Island experienced such dissonances in real-time, trying to determine the threat levels from an unfolding and unprecedented event, ABC News sent reporters to Middletown.

“Tonight, many people in Middletown are nervous. More of them moved bedding to this sports arena, eleven miles from the power plant. Civil defense officials said about twelve-hundred people in all have left their homes from around the plant to go to shelters. Earlier, some drove to friends’ houses in a moment of high anxiety when schools were closed and parents arrived to pick up their children.”8

“It’s a lot worse than what they’re telling us,” shouts a local to the ABC camera operator. “Typical lies. They ought to close all those nuclear power plants down.”

Four decades on, we might describe Del Tredici’s image as Lynchian, as in recalling the formal and affective vocabularies of the late American film and television director David Lynch.

In 1996, American author David Foster Wallace neatly defined Lynchian as “a particular kind of irony where the very macabre and the very mundane combine in such a way as to reveal the former's perpetual containment within the latter”9.

That is to say, horror has always lurked beneath both the everyday-blandness of American suburbia and the antiseptic, sugary sheen of Hollywood storytelling about America.

Near the end of that ABC clip, a local woman, Marilyn Shope, speaks to a reporter from the doorway of her home. “I don’t think the radiation is really going to be affecting our health,” she says. “I really don’t—if they’re telling us the truth now.”

It bears mentioning here that just four days before Del Tredici shot his Yellow Brick Road photograph, 2,000 miles to the west, a uranium slurry holding pond, located at Church Rock, New Mexico, on the Navajo Nation, failed. The supposedly state-of-the-art holding pond was filled with toxic waste produced by a nearby uranium mill owned by the United Nuclear Corporation.

Above is a drone photograph of the site by Diné interdisciplinary artist Will Wilson, whose work we’ll explore more deeply in future installments of Time Zero. Note the date: 2019. These toxic ponds remain in use to this day.

What is especially eerie about the Church Rock spill is that the holding walls on the pond burst open at 5:30 a.m. on July 16, 1979, essentially 34 years to the minute of the Trinity Test.

Almost immediately, the spill dumped 94 million gallons of radioactive waste into the Puerco River, contaminating ecosystems across state lines. Contained in those highly acidic and saline 94 million gallons of radioactive water was 1,100 short tons of solid radioactive waste, including heavy metals (like uranium) and sulfates, all of which were byproducts of the United Nuclear Corporations uranium milling10.

The Church Rock spill remains the single largest release of radioactive material in US history, having unleashed more than three times the radiation emitted from the Three Mile Island meltdown a few months earlier11. And yet most people have never heard about it.

“I feel like the Church Rock spill, the first big articles that I remember reading about it came out in the last five years,” said artist Anna Tsouhlarakis. “And that’s insane that it’s just entering some areas of mainstream conversation.”

Tsouhlarakis is an enrolled citizen of the Navajo Nation, also of Greek and Creek descent, who grew up between New Mexico and Kansas. Today, she’s an associate professor at the University of Colorado, Boulder. We spoke over a video call in August 2024.

“You know, we call watch Chernobyl on HBO, but what does that mean when Chernobyl actually happened only, you know, a hundred miles from you? I think about all the people who live in Albuquerque and Santa Fe and how, had they been in a different country, maybe they would have been evacuated because they were actually within a certain zone that should have been deemed a no-go-zone.”

Her family was much closer to the Church Rock spill than the residents of Albuquerque or Santa Fe. They lived adjacent to the holding ponds.

Neither the United Nuclear Corporation nor government officials made any real immediate efforts to warn the Navajo—or Diné—residents who lived along the Puerco to avoid the now-radioactive water. Then-New Mexico Governor Bruce King declined the Navajos’ request to declare a federal disaster, which would have provided considerable real-time aid to residents.

This process of commodifying, exploiting, and actually racializing landscapes is what environmental historian Traci Brynne Voyles calls “wastelanding.” She described this to me when we spoke over a video call in July 2024.

“As I was looking at the process of wastelanding, and how it evolved over time, the way that I came to understand this projection outside of human bodies is that our perceptions of race and racial power were actually extending to places as well.”

In her 2015 book Wastelanding: Legacies of Uranium Mining in Navajo Country, Voyles uses wastelanding as a verb; the active designation of an environmental space as pollutable.

“And so in this case, marking the area around the Navajo homeland as Indigenous or Diné land actually fueled settler, governmental, and business interest in this extractivist mode. And because settler relationships to Native peoples have always been organized around extraction and dispossession, it came to be extended to relationships to the land as well.”

Following World War II, the US government guaranteed the purchase of all uranium mined domestically. The secretive wartime US nuclear program had produced a postwar arms race with the Soviet Union, and guaranteed purchases incentivized private companies to keep digging.

Doing the actual digging were local Navajo.

By 1971, the government decided that it had stockpiled a sufficient amount of uranium for the foreseeable future. So, the purchasing guarantee dissolved.

Overnight, many private companies simply declared bankruptcy and left, abandoning hundreds of radioactive mines across the Four Corners region of New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, and Utah. An enormous number of those—500, by most estimates12, though some have speculated that it may be as many as 1000—sit unremediated on Navajo land, slowly poisoning the Diné people.

Alongside many of those abandoned mines and mills on the Navajo Nation were what are called tailings piles—giant mountains of what appear to be sand and dirt. But those earthy mounds are laced with mining ore residue containing radioactive decay products from uranium, as well as heavy metals. Uninformed of the risks, some Diné gathered contaminated tailings pile sand to build homes, inadvertently endangering themselves and future generations.

Nuclear material perverts, poisons, and kills water bodies, plant life, human and nonhuman animals, and the land itself. Nuclear waste and radioactive fallout are, as far as you and I understand time, essentially forever.

The term half-life refers to the interval of time that’s required for half of the atomic nuclei of a radioactive bit of material to decay.

The half-life of plutonium is 24,000 years, twice as long as it’s been since humans learned to farm in Mesopotamia, and 23,920 years longer than it’s been since the Trinity explosion in New Mexico.

And the half-life of uranium? The element released en masse into waterways during the Church Rock spill just decades ago, and what’s in and around those abandoned mines?

Four-and-a-half billion years. That is the approximate age of Planet Earth.

Over the last several years, as I’ve been devoting the vast majority of my art production, writing, and field research towards better understanding the nuclearized world, I’ve been frequently asked: Why, exactly, am I so interested in all of this?

I’m not Native. I used to live in the Southwest, but I’m not from there. My family doesn’t live there. So, what’s my angle?

It’s a fair question, and one I’ve given a lot of thought to.

Growing up at the tail end of the Cold War, I definitely had an ambient awareness of the potential for nuclear war, and plenty of television shows and movies depicted radiation, nuclear meltdowns, and toxic sludge. But that’s not a unique experience for an American elder-millennial and, although technically foundational, it’s not why I’m doing this.

I also want to be clear that I’m also not “into” World War II.

I grew interested in these histories over the course of several years road tripping and backpacking around the Western United States. Seemingly every desert, mountain range, and town had some connection to the US military infrastructure, if you looked hard enough.

Eventually, before any trip, I’d study the interactive online land use database map hosted by the Center for Land Use Interpretation, locating missile ranges, bombing fields, and Manhattan Project detritus along my routes. I started writing more and more about the so-called West for arts magazines, and the ongoing reality of the nuclear—what felt like part of an almost-science-fictional past—became inescapable.

When I started to interview communities who lived downwind or downstream of nuclear testing sites and production facilities, especially in and around the Four Corners, I heard countless stories of family members dying cruel deaths from cancer, generation after generation, since 1945. At the time, my own dad was dying of prostate cancer. I watched him die slowly, excruciatingly, in immense and increasing pain, over an entire calendar year.

I considered how such a loss would have felt had his death been the result of his having been knowingly—and casually—poisoned by the United States government. Treated like a lab rat.

Can you even fathom the anger that these people must feel?

Months later, my younger sister was diagnosed with triple-negative breast cancer, an obscenely aggressive disease that primarily affects young people. Like all the women in my family, she has what’s called a BRCA2 mutation—an inherited, harmful gene change that radically increases one’s chances of getting cancer. The number of cancer diagnoses, as well as non-elective and preventative bilateral mastectomies, hysterectomies, and salpingo-oophorectomies, that my sisters, mom, aunts, and cousins have had is staggering. Again, I think about how it would feel to know that such genetic mutations were the result of the military-industrial complex, and I’m livid.

Of course, I went searching for explanations for my own family’s cancers. Something beyond genetics.

The following highlights of what I learned are all, technically speaking, geographically coincidental. I can’t prove causal relationships, nor do I mean to imply them. But through this research I’ve certainly gained a more critical and sobering understanding of the everywhere-ness of US nuclear presents, pasts, and futures.

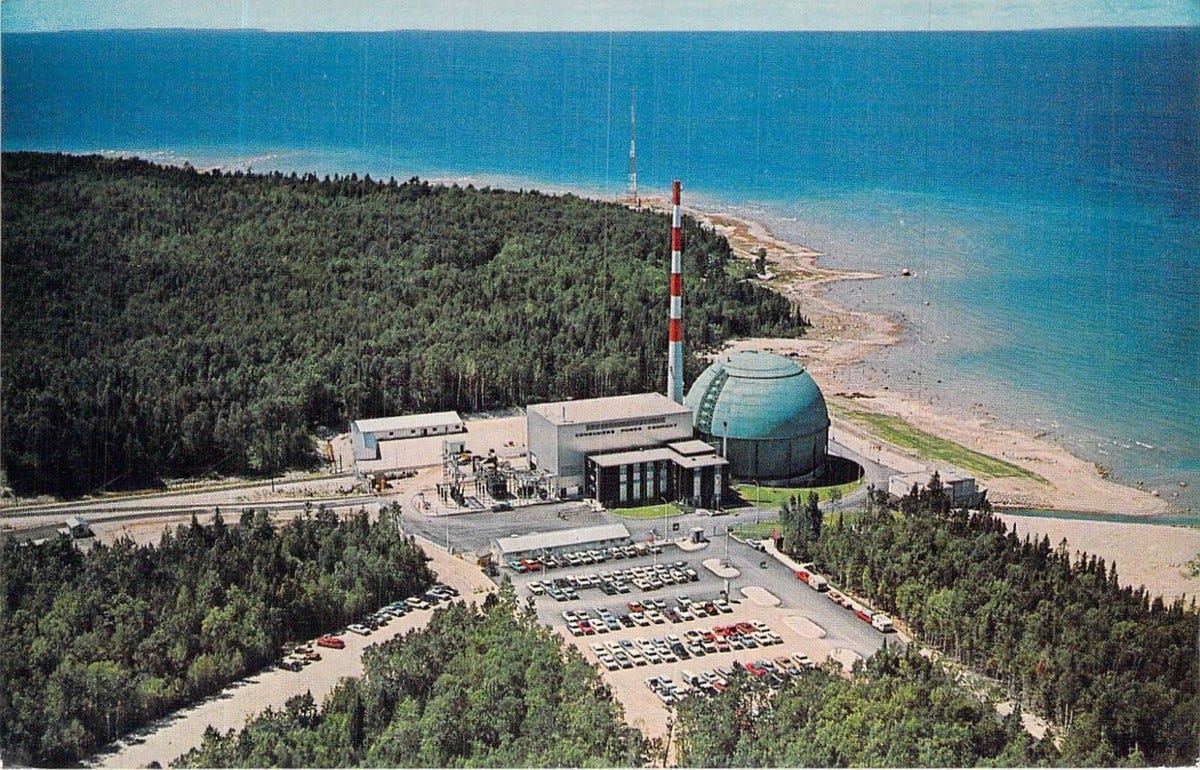

It turns out that where my sisters and I grew up in Northern Michigan is just 50 miles from the Big Rock Point Nuclear Power Plant, the state’s first and the nation’s fifth such atomic facility. It was decommissioned in 1997, but to this day, the site is home to eight massive dry storage casks, each nineteen feet tall, that hold a total of 58.6 metric tons of nuclear waste13.

There’s nowhere to send it, you see.

My mom, who was born in 1950, and her sisters grew up in Buffalo, New York, within 30 miles of two radioactive dump sites, a former commercial nuclear fuel reprocessing facility, a uranium and thorium metals processing mill, and the famously toxic Love Canal, into which the Hooker Chemical company dumped almost 20,000 long tons of chemical waste throughout the 1940s14.

My mom’s mom worked at Hooker Chemical, before dying at 43 of what might have been leukemia, though, because of the way that cancer was minimized or hidden at the time, nobody still alive in my family seems to know for sure.

My dad, who was originally diagnosed with prostate cancer at 55—extremely young, statistically speaking—grew up in Detroit, where municipal water was pulled from the Detroit River, at the time one of the most polluted waterways in the United States15. During the Manhattan Project, a plant on the river fabricated components for atomic weapons using uranium and sundry toxic chemicals. Later, it manufactured uranium fuel rods. The property, where radioactive waste was still being stored, collapsed into the Detroit River in 2019. Two years later, it happened again.

Denver, where my sister who had cancer has lived for over a decade, is next door to Rocky Flats, the site of a Cold War-era plutonium pit processing facility that was so environmentally unhinged that the FBI and EPA raided it in 1989 and shut it down. Plutonium pits are the active, fissionable component that make nuclear bombs nuclear bombs. Rocky Flats, which is listed on the Superfund National Priorities List, is now a wildlife refuge, and is open to hikers.

Again, the half-life of plutonium—which was all over Rocky Flats—is 24,000 years.

All of this, though, is, objectively speaking, circumstantial information. My suspicions are pure speculation. I could never prove a causal relationship between their cancers and these environments, which is something that industrialists, the military, and the US government have understood pretty clearly for 80 years.

What motivates me here to collate and broadcast nuclear histories is that there are thousands of families whose rates of cancer can be easily linked to environmental factors. Take the Trinity Downwinders, for example, who were literally nuked. And yet the federal government refuses to be accountable to, or even acknowledge, their suffering. And the program that does exist to make amends to some victims of the US nuclear infrastructure—the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act, or RECA—is selective and wholly insufficient.

I should note that, following the recording of the first episode of Time Zero, a reauthorization of RECA was surprisingly added onto the Trump administration’s One Big Beautiful Bill Act. This comes after the same proposed legislation stalled in the House last year after passing the Senate. This addendum was included, ostensibly, to convince Senator Josh Hawley (R - Missouri) to vote in favor of the bill’s existing cuts to Medicaid. Whether it makes it through the final stages of negotiations before a vote, remains to be seen.

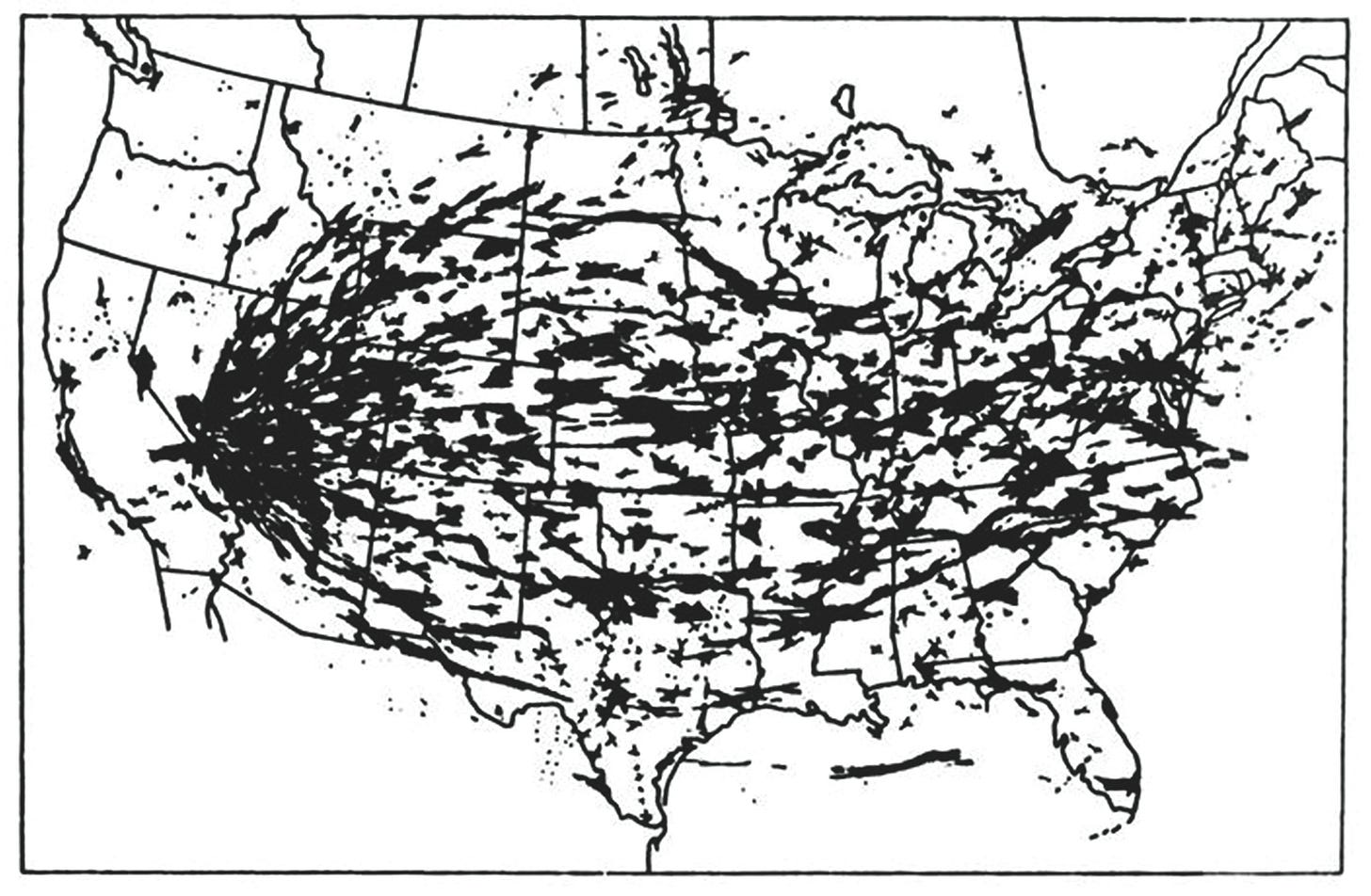

There’s a famous graphic in anti-nuclear activist circles, created by researcher Richard Miller, showing the lower 48 United States, splattered, Jackson Pollock-style, with black blotches emanating from the bottom of Nevada. Each black blob denotes an area crossed by two or more radioactive clouds during the era of atmospheric nuclear testing in the American Southwest, 1951-62, which Miller painstakingly collated through official data from the Atomic Energy Commission.

In the United States, the nuclear is everywhere: from aboveground storage ponds and dry casks of high-level nuclear waste; to “low-power” nuclear reactors inside unassuming buildings on university campuses; to the South Rim of the Grand Canyon, where, last year, the Energy Fuels corporation activated Pinyon Plain, a domestic uranium mine.

It’s true that none of my own family members lives in the American Southwest, the desert-defined landscapes with which most Americans might historically associate nuclear activities. And yet each of them has, more or less, always lived within an hour of a nuclear power plant, a radioactive dump, a uranium processing facility, or a plutonium-tainted Superfund site.

Three years after the Church Rock spill, in 1982, United Nuclear Corporation closed its mill and left the Navajo Nation without undertaking any cleanup efforts. To this day, Red Water Pond Road Community members live with the environmental aftermath of the Church Rock disaster.

The subjecting of marginalized populations—especially Indigenous communities—to the lethal dangers of nuclear industries and testing is not unique to the United States, but we’re certainly the architects behind what’s referred to as “nuclear colonialism” which, like all things nuclear, traces back to 1940s New Mexico.

In June 2024, I connected with Dr. Myrriah Gómez, a Nueovomexicana from the Pojoaque Valley in northern New Mexico. We met up in Albuquerque, on the campus of the University of New Mexico, where she’s an associate professor in the Honors College. Dr. Gómez’s 2022 book Nuclear Nuevo México: Colonialism and the Effects of the Nuclear Industrial Complex on Nuevomexicanos has been instrumental in my own understanding of nuclear legacies, especially in the American Southwest.

“Nuclear colonialism,” said Dr. Gómez, “in thinking about it as the third major period of settler-colonialism in New Mexico, on the one hand, it’s talking about how it—the nuclear era, nuclear colonialism, nuclear everything—started here in the 1940s. Literally, we’re ground zero for everything nuclear, because of Site Y, or Project Y, of the Manhattan Project.”

That’s the original 1940s military codename for what is today Los Alamos National Laboratory, above Santa Fe on the Pajarito Plateau.

“But also it also means considering,” Dr. Gómez continued, “we’re past eighty years now in thinking about colonialism. And the settlers came—these were the scientists, the military personnel, and everybody who came with them—and they never left.”

The Pajarito Plateau in the Jemez Mountains, northwest of Santa Fe, has been home to Indigenous communities for at least 11,000 years. By the mid-19th century, the Plateau was occupied by diverse communities who used the land for hunting, gathering, and livestock grazing. Among these were Pueblo and Athabaskan peoples, alongside Anglo and Hispanic Americans of Mexican and Spanish descent, many of whom had received land grants from the Spanish and later Mexican governments.

In 1917, Detroit businessman Ashley Pond, Jr. established a boy’s ranch school on the plateau. Some of its more famous students include Gore Vidal and William S Burroughs.

During World War II, the US Army seized the plateau to create Site Y, where physicist J Robert Oppenheimer and General Leslie R Groves led the highly secretive Manhattan Project to develop the atomic bomb.

Today, Los Alamos National Laboratory boasts its contributions to fields like Mars exploration, human genome sequencing, and artificial intelligence. However, its priorities remain clear: of its $5.15 billion 2024 Congressional budget request, 78.8%—over $4 billion—was allocated to nuclear weapons development16.

Walking around the town of Los Alamos today feels surreal. The wealthy, guarded military-science village, which is dotted with microbreweries and surrounded by networks of hiking trails, literally looks down upon surrounding communities like Santa Clara and San Ildefonso Pueblos, and Española, an underserved city north of Santa Fe now facing gentrification by the type of pathologically altruistic white liberals satirized in Nathan Fielder and Benny Safdie’s jet black comedy The Curse.

In June of 2024, after participating in the Manhattan Project National Park “Behind the Fence” tour of Los Alamos—more on that in a future installment of Time Zero—I ate my lunch in a downtown Los Alamos park, where a small but lively local Pride parade made laps around Ashley Pond, an artificial waterbody named for the founder of the Los Alamos Ranch School for Boys.

Several of the people marching were lab employees; I recognized them from the bus tour that morning, where they were sporting t-shirts emblazoned with the rainbow logo for Prism, the lab’s LGBTQ+ Employee Resource Group (which has since, it appears, been scrubbed from the LANL website, presumably during the anti-DEI crackdown, but related social media posts remained online as of June 2025). The employees had been talking openly about work at the lab. Some marchers, though not those I’d clocked for sure as lab employees, carried signs expressing solidarity with the people of Palestine.

It was a disquieting, dissonant, and horrifically ironic affair. A march for equality and love and, by extension, one might argue, peace, by the people who are making atomic bombs.

I wondered, did these people, through some lab-designed, byzantine informational compartmentalization, possibly believe that their jobs at Los Alamos had something to do with identifying cool rocks on Mars, or helping to solve climate change, as opposed to, say, permanently poisoning the waterways, flora, fauna, and people in the canyons below the laboratory in service of building civilization-ending weapons of mass destruction?

It is not simply the threat of radiation exposure from the nuclear industry that hangs over every living thing on the planet today. We also each navigate—or avoid, subconsciously or intentionally—a deeply personal psychological relationship with the ever-present reality that, at any moment, we are but minutes from potential nuclear annihilation.

Example: an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) fired from Russia or North Korea would hit the city of Los Angeles in about 30 minutes. A submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) could strike in seven to 12 minutes. There are likely at least five Russian nuclear submarines currently active in the oceans17.

We, the United States, continuously operate about a dozen Ohio-class submarines across the globe, each armed with up to 20 Trident II missiles18. These missiles carry four nuclear warheads apiece. Each warhead delivers 475 kilotons—a figure 3,000% more powerful than the bomb we exploded over Hiroshima. So, right now, US submarines are sitting under the ocean with, potentially, nearly 1,000 nuclear warheads, primed for immediate deployment.

In the 2024 book Nuclear War: A Scenario, journalist Annie Jacobsen presents a chillingly plausible sequence of apocalyptic events. It begins with North Korea launching an ICBM at Washington, DC, followed by an SLBM targeting the Diablo Canyon Nuclear Power Plant in San Luis Obispo, California.

This catastrophic double-strike—a nuclear weapon hitting a nuclear power facility—is known, fittingly, as the Devil’s Scenario, an almost unfathomable manifestation of Hell on Earth.

Technically speaking, the targeting of a nuclear power plant with a nuclear weapon is a violation of the Geneva Convention, which, I mean, thank God, right?

Once a US military satellite detects the ICBM’s launch, the President has six minutes to decide on a retaliation strategy via what amounts to what Jacobsen describes as “a Denny’s menu of death” contained in a satchel you’ve probably heard of: the Nuclear Football.

The most likely scenario involves the launch of 1,770 US readied nuclear weapons—ICBMs, aerial bombs, and submarine missiles, many of which will be carrying multiple warheads—under the “use them or lose them” doctrine. Russian satellites detect US ICBMs but lack the precision to determine the North Korean destination. Perceiving an existential threat, with only minutes to react, Russia retaliates with their own 1,710 deployed nuclear weapons.

There are currently nine nuclear nations: the United States, Russia, North Korea, China, the United Kingdom, France, India, Pakistan, and Israel. Official policy for each dictates no deescalation once a nuclear weapon is used. The outcome is always absolute, total nuclear war.

Public misconceptions about America’s missile defense capabilities abound, says Jacobsen; the Ground-Based Midcourse Defense system has just 44 interceptor missiles. Those 44 missiles have a success rate of 55%. They cannot stop submarine-launched missiles, and ICMBs almost always carry dummy warheads, so even if an interceptor were to actually hit one of the several thousand warheads raining down onto the United States, there is a decent chance that that specific warhead was a decoy.

In short, the system is useless.

In Jacobsen’s scenario, within 72 minutes, 60% of the global population is annihilated. Survivors face horrific radiation, as well as nuclear winter, as ash blocks sunlight for decades, freezing water and killing crops. When temperatures rise years later, billions of decomposing bodies will unleash a second calamity: catastrophic plagues19.

“A war today or tomorrow, if it led to nuclear war, would not be like any war in history. A full-scale nuclear exchange, lasting less than 60 minutes, with the weapons now in existence, could wipe out more than 300 million Americans, Europeans, and Russians, as well as untold numbers elsewhere. And as Chairman Khrushchev warned the Communist Chinese, ‘the survivors would envy the dead.’

John F Kennedy, July 26, 196320

Anthropologist Joseph Masco has written extensively about the psychological paradoxes of living in a nuclearized world. Building off of Freud’s concept of the uncanny—which identified not a feeling of unfamiliarity, per se, but rather, quite specifically, a disconcerting feeling of unhomeliness—Masco introduced the concept of the “nuclear uncanny” in his 2006 book The Nuclear Borderlands: The Manhattan Project in Post-Cold War New Mexico.

“That was a project that involved interviewing people who worked on nuclear weapons for a living, but also multiple and diverse communities that have lived around the laboratory and have very different relationships to both nuclear weapons and US national security.”

Masco and I spoke over video chat in July 2024. He relayed that, in asking these communities about their experiences and feelings about nuclear weapons work at Los Alamos, he often heard what he described as “a very strange kind of narrative answer” that had to do with two different aspects of nuclearity.

“One had to do with the idea of a potential nuclear war that could always have already started, because the US, since the early 1960s, has lived within a 15-minute launch window for full out nuclear war. If you think about that just for a second, it would mean, at any given moment of the day, it might have already started and you just don't know it yet.”

So, Masco explained, that's one kind of strange derangement of the senses.

“The other one has to do with radiation itself, and the fact that so many of the materials involved in producing nuclear weapons—also questions around nuclear power plants and nuclear waste—have to do with things that are invisible, but that are a source of harm. It became very clear to me that one of the things that was most disturbing about living around a nuclear site is the fact that one can’t know what the level of danger is at any given moment. And so, the nuclear uncanny, as a concept, is trying to explain that by saying that one of the effects of nuclear processes—nuclear technologies, nuclear waste, nuclear fallout—is that one can’t trust one’s own senses anymore.

If all of this feels overwhelming, that’s understandable. The nuclear as a concept—the weapons, the mining, the power, the waste, the timelines—is so massive that it might be described as what the philosopher Timothy Morton calls a hyperobject.

A hyperobject is something that simultaneously occupies so much time and space, and is so weird and impossible to fully wrap our heads around, that it makes us feel completely powerless. Humiliated even. Other hyperobjects include climate change, black holes, and, physically and philosophically, plastic.

But the thing is, we unearthed the nuclear. It’s not a black hole. And, just like with fossil fuels, we can stop using it.

Through the arc of Time Zero, we’ll hear from artists who use speculative fiction and other strategies to propose exciting and radical, post-nuclear futures. And we’ll talk with the people on the ground—regular people—who are working to slay this completely unnecessary monster.

The first step is confronting the reality that the Atomic Era never ended, and that it’s everywhere, all the time. As of today, we’ve already taken that step.

The people in charge of America’s nuclear weapons and atomic energy are betting that you and I will indeed be overwhelmed by the hyperobject of the nuclear. They want us to be so afraid of Russia, North Korea, and China that we don’t question the rebuilding of the entire US nuclear arsenal, which is going to cost $1.7 trillion over the next 30 years21, right out of our paychecks.

And on the environmental side of things, they’re banking that you equate the nuclear industry with mythologically remote regions of the American Southwest. Or, they hope you’ll simply shrug and say, “Do any of these environmental issues even concern me? I don’t live anywhere near Los Alamos National Laboratory.”

If you did a quick internet search for maps detailing current radioactive surface storage sites across the US, which hold 90,000 metric tons of nuclear waste in storage ponds and aboveground casks22, you’d find that about 70% of US states have them.

You can easily locate transportation routes that move transuranic waste from those nuclear facilities—the ones that Abbey Hepner photographed—to the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant near Carlsbad. They move it in unmarked trucks, all over the country, on the same Interstates that you and I drive.

Revisit Richard Miller’s overlapping fallout map.

Even Wikipedia is going to show you a map of twenty major Manhattan Project production sites, pretty much all of which are wildly contaminated. Though that doesn’t even begin to scratch the surface of the dizzying number of industrial plants across the US that were subcontracted then, and throughout the Cold War, to produce uranium fuel rods, plutonium pits, and other atomic weapons components.

You can look up locations of 94 currently operational nuclear power reactors in the US, and our 400 underground intercontinental ballistic missile silos.

The DOE’s own website admits that the US government purchased defense program uranium from 4,225 uranium mines spread across New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, Nevada, Colorado, Wyoming, Idaho, Montana, Oregon, and California23. Virtually all 4,225 of those uranium mines have been abandoned.

You could read about Coldwater Creek near St. Louis; or the Savannah River Site in South Carolina; Pantex in Lubbock, Texas; or Mound Laboratory outside of Dayton, Ohio.

Look these up, and consider for a moment:

Where does your family live?

“March 28, 1979: Three Mile Island nuclear power plant accident.” YouTube, uploaded by CBS News, 28 March 2019.

This figure of 250,000 deaths, over time, is what I believe to be a relatively conservative estimate, based on a wide variety of sources, including: The International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons. “Hiroshima and Nagasaki Bombings.”; Wellerstein, Alex. “Counting the dead at Hiroshima and Nagasaki.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 4 August 2020.; National Archives. “The Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.”; and multiple other sources.

Arms Control Association. “The Nuclear Testing Tally: Fact Sheets & Briefs.” January 2024. Accessed 29 September 2024.

US Department of Energy. “5 Facts to Know About Three Mile Island.” 4 May 2022. Accessed 14 October 2024.

The Associated Press. “14-year cleanup at Three Mile Island concludes.” The New York Times, 15 August 1993.

Nuclear Regulatory Commission. “Background on the Three Mile Island Accident.” Last updated 28 March 2024. Accessed 11 October 2024.

“In Conversation with Robert Del Tredici: Photographers of Devour the Land.” YouTube, uploaded by Harvard Art Museum, 07 November 2021.

“Three Mile Island, Safety Fears in 1979.” YouTube, uploaded by ABC News, 12 March 2011.

Wallace, David Foster. “David Lynch Keeps His Head.” Premiere. September 1996. Later reprinted in: Wallace, David Foster. A Supposedly Fun Thing I'll Never Do Again: Essays and Arguments. 1997.

Wirt, Lauri. "Radioactivity in the Environment: A Case Study of the Puerco and Little Colorado River Basins, Arizona and New Mexico." Tucson, AZ: US Geological Survey Water Investigations Report 94-4192. 1994.

Arnold, Carrie. “Once upon a mine: the legacy of uranium on the Navajo Nation.” Environmental Health Perspectives. February 2014.

Environmental Protection Agency. “Abandoned Mines Cleanup.” Accessed 11 October 2024.

US Department of Energy. “Big Rock Point: Operation, decommissioning, and the interim storage of spent nuclear fuel.” PDF. 1 November 2012.

Environmental Protection Agency. “Superfund Site: Love Canal, Niagara Falls, NY: Cleanup Activities.” Accessed 09 August 2024.

Hartig, Jon. “Great Lakes Moment: Lest we forget - A history of Detroit River oil pollution.” Great Lakes Now (Detroit PBS). 05 February 2024.

Nuclear Watch New Mexico. “Los Alamos National Laboratory FY 2024 Congressional Budget Request.” PDF. June 2023.

Nuclear Threat Initiative. “Russia Submarine Capabilities.” 28 August 2024. Accessed 22 November 2024.

Nuclear Threat Initiative. “United States Submarine Capabilities.” 12 August 2024. Accessed 22 November 2024.

Jacobsen, Annie. Nuclear War: A Scenario. 2024.

“Radio and Television Address to the American People on the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, July 26, 1963.” John F Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum.

Hennigan, W.J. “The Price.” The New York Times. 10 October 2024.

US Government Accountability Office. “Nuclear Waste Disposal.” Accessed 14 September 2024.

US Department of Energy. “Abandoned Uranium Mines Working Group Addressing Health and Safety Risks of Abandoned Uranium Mines Multiagency Strategic Plan.” PDF. 3 December 2022.

How I wish I had clocked that 35 years to the minute fact before the final edit of Demon Mineral!