02: 05:29 a.m. Mountain War Time

In less than one second, everything is going to change. Forever.

02: 05:29 a.m. Mountain War Time

NOTE: you can listen to this episode using the player linked above, or for free on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

You can also access the full copy of the essay version below at timezeropod.com.

It is 5:29 a.m, Mountain War Time, on July 16, 1945.

We are in the Chihuahuan Desert of southern New Mexico, standing at the northern reach of the Tularosa Basin. To the east stand the Sacramento Mountains. To the west, the San Andres.

Fifty miles south are the famous White Sands dunes, a 275-square-mile undulation of blindingly bleached gypsum crystals. The winds down there are as animated as the winds up here, shifting the dunes endlessly. White Sands is a topography in perpetual motion. Sometimes, the wind blows in just such a way that it reveals otherwise-covered layers of sediment from a long-dried lakebed.

Seventy-five years from now, in the 21st century, scientists will locate fossilized footprints in the sediment that they’ll carbon date to 21,000 BCE.

The people that these footprints belonged to wandered around that ancient lake alongside giant sloths and mammoths. It is essentially impossible to appreciate such a length of time: two dozen millennia. Geologic in scale.

In our immediate timeline, however, less than one second from now, everything is going to change. And I mean everything. From the sand in this desert, to plants across this continent, to the glaciers of Antarctica, to the very bones inside of your body and mine.

Everything is going to change. Forever.

“We know that the Trinity atomic bomb was a very problematic bomb,” says Mary Martinez White, “because of the weapons-grade plutonium that is still out there, still as active as it was the day that it was put into the atmosphere—and will be for 24,000 years. Hard to wrap your head around that.”

It was a sunny morning in early June 2024, and I had met up with Mary in a park in Santa Fe for coffee, and to interview her for the podcast.

“I was born and raised in Tularosa, New Mexico,” she said into the recorder. “Forty-five miles from the Trinity atomic bomb.”

Mary and I had originally met in 2023 when she helped to organize Trinity: Legacies of Nuclear Testing - A People’s Perspective, an exhibition at the Branigan Cultural Center in Las Cruces, where she lives today, about an hour southwest of Tularosa. I was covering the show for High Country News and over months of emails, phone calls, and then finally connecting IRL at the opening, got to know Mary pretty well.

For several years, Mary has been on the steering committee of the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium—often referred to as the Trinity Downwinders—a citizen-led group from southern New Mexico who want justice for what they describe as the “unknowing, unwilling, and uncompensated victims” of the world’s first atomic blast, Trinity1.

We were both in Santa Fe to catch screenings of First We Bombed New Mexico, a 2023 documentary by Lois Lipman about the Trinity Downwinders.

Since the Trinity detonation on July 16, 1945, generations of Tularosa Basin residents have been plagued by cancer.

Later that day, in a café adjacent to the cinema hosting the screening, I met up with Tina Cordova, who had also helped to organize the exhibition the previous summer. I set up the mic and Tina quickly introduced herself with a rehearsed rhythm.

“My name is Tina Cordova. I’m a native New Mexican, I’m a downwinder, and I’m a cancer survivor.”

She’s done hundreds of these interviews.

“And I’m a co-founder of the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium.”

In Lipman’s documentary, Tina, is the central character. She started the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium in 2005 with the late Fred Tyler. Today, the group is steered by Tina, Mary, educator and musician Paul Pino, Dr. Alicia Romero, artist Joanna Keane Lopez, Christy Pino, Joaquin Lujan, and and Bernice Gutierrez, who was born in Carrizozo, New Mexico, eight days before the US military set off the world’s first nuclear weapon just thirty-five miles west of her family’s home.

For two decades, the Trinity Downwinders have been fighting for an expansion of the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act, or RECA. Voted into law in 1990, RECA provides partial, one-time restitution to people who got certain forms of cancer while living in a handful of counties in Utah, Nevada, and Arizona, located downwind from the Nevada Test Site, 65 miles north of Las Vegas, where the United States detonated one hundred above ground nuclear bombs between 1951 and 1962.

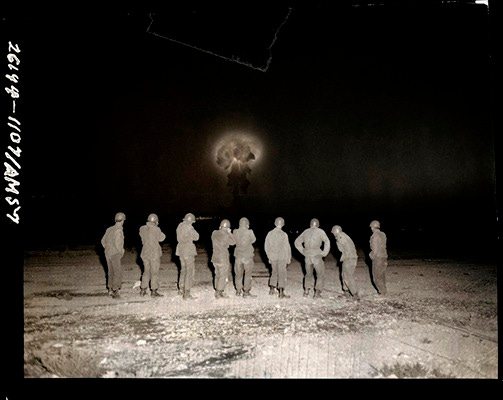

RECA also provides partial financial compensation for Nevada Test Site workers who contracted cancer, as well as military veterans who took part in live exercises like the Desert Rock “Atomic Maneuver Battalion” series at the Nevada Test Site, where platoons were marched toward smoldering mushroom clouds “to test military equipment”2.

You might also be eligible for RECA if you contracted certain types of cancer after working in domestic uranium mining, milling, and transport industries—but only if you did so up until 1971. That year, the US government stopped its guaranteed defense program purchasing of privately mined uranium3, so, even though the US military was the singular reason that uranium mining exploded in the first place, if you started working for a mining company after that date, you’re out of luck.

RECA has never included the people who live near the Trinity site in New Mexico.

A note about RECA and Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill…

As mentioned in the previous installment of Time Zero, after this episode had already been recorded, there was surprise motion when, in mid-June, outlets reported that an extension and expansion of RECA had been added onto the One Big Beautiful Bill (the Trump administration’s domestic spending proposal).

This would extend benefits to the Trinity Downwinders and others, including post-1971 uranium mining workers, and radiation-affected populations in Alaska, Kentucky, Tennessee, Guam, and Hawley’s own Missouri constituencies. The measure would also “increase benefit levels for atmospheric testing survivors to track inflation”4.

This last-minute adjustment was seemingly designed to appeal to Senator Josh Hawley (R - Missouri)5, who had expressed who expressed concerns about the legislation’s massive cuts to Medicaid6. Because Missouri has a handful of sites that have been contaminated for decades with nuclear waste leftover from the Manhattan Project7, Senator Hawley has been vocally pro-RECA expansion.

On Tuesday, July 1, the One Big Beautiful Bill, which had narrowly cleared the House in May, was approved 51-50 by the Senate , courtesy of a tie-breaking vote by Vice President JD Vance. Three Republicans voted against the bill, which included $1 trillion in cuts to federal health care spending8. Hawley wasn’t one of them.

The bill now returns to the House, who will review changes proposed by the Senate—including the RECA expansion and extension. If the House approves it, the bill will head to President Trump’s desk. Legislators have a self-imposed deadline of July 4, though it’s unclear if they will formally have ironed things out by then.

An email from the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium went out on Monday, June 30, with a message from Tina that included the following context:

While this is good news for those of us in New Mexico who’ve been waiting 80 years for acknowledgement and assistance, our fight is not over. We are dedicated to a more permanent fix that includes all of our sisters and brothers from across the American west and Guam that have been affected. It is likely the two-year extension will not be adequate time to enroll all the people from New Mexico that have been affected9.

As I was following along, I was struck by how familiar the White House’s legislation status meter looked to something that I’d seen many times before…

Please keep these late-breaking changes in mind as you read the rest of this text, though they do little to alter the reality of what Trinity-affected people have been dealing with for eight decades.

For Mary Martinez White, Tina Cordova, and the rest of the Trinity Downwinders, the compensation that RECA provides is far less important than the accountability—the acknowledgment of harm and wrongdoing—that would come with the expansion of the program.

And when I say the compensation is partial, I mean partial: a one-time $50,000 payment if you got specific cancers from living in a landscape poisoned by nuclear blasts10.

How far does $50,000 go towards cancer care? To put it into perspective, while my sister was undergoing cancer treatment, the bill the hospital submitted to her insurer for just one of her procedures was a quarter of a million dollars.

Despite Senate approval in spring 2024 to add Tularosa Basin downwinders and other groups to RECA’s scope, the program expired last June after stalling in the House of Representatives when House Speaker Mike Johnson (R - Louisiana) refused to allow a vote. The Department of Justice has since stopped processing claims.

First We Bombed New Mexico screened in Santa Fe to sold out crowds on June 7 and 8, 2024, just as RECA expired. What so many of us had hoped would be a victory lap—the bill had cleared the Senate with bipartisan support—became a more solemn affair.

The first night, after the screening, there was a very charged discussion between Tina and director Lois Lipman moderated by Dr. Myrriah Gómez, author of Nuclear Nuevo Mexico, whom we met in episode one.

On the second night, Tina and Lois Lipman were joined by Trinity downwinder Paul Pino, as well as New Mexico Congressperson Teresa Leger Fernández. At one point, Tina looked out at the packed audience, many of whom were likely recent transplants to New Mexico, and articulated Trinity’s slow violences—the physical, yes, but also the mental and financial.

Many of you are not native like we are. Many of you have chosen to live in this beautiful place. But we have blemishes, and this is one of those blemishes. And let me just tell you, you may not identify as a downwinder, but you’ve been affected. New Mexico is one the states carrying the highest medical debt in the country. We have a little over two-million people living here. We’re carrying $881M in medical debt. That’s not a sustainable equation. That’s why we’re fighting for this, because this has taken our lives. It’s affected us emotionally and psychologically and it’s taken our finances. It’s taken what we have available to us, to pass on, to contribute.

It is still dark here in New Mexico’s vast Tularosa Basin.

It’ll be another 37 minutes before the sun climbs over the Sacramentos, and so this landscape’s patterns of succulents, patches of wiry grass, and occasional yucca are all but invisible, discernible only as shadows of shadows.

The dark that surrounds us swallows us whole. It is enormous and dislocating, an atmospheric blackness that you’ll certainly understand if you’ve ever spent a night near Socorro, just north of us, or Carrizozo, New Mexico, thirty-five miles to the east, where downwinder Bernice Gutierrez was born eight days ago. It’s the sort of darkness you’d experience camping on the North Rim of the Grand Canyon, or at Big Bend in West Texas.

Besides the winds, which are said to blow in every direction at once in the Tularosa Basin, it is quiet. It is still. Overnight thunderstorms—with their spectacular stabs of spidery lightning and torrents of Biblical rains—have paused, at least for now.

It is important to understand—in fact, it is imperative to this story that you understand—that July is monsoon season in southern New Mexico. Storms descend almost daily, pummeling the parched earth with much-needed moisture. In especially stormy years, the tree-like cane cholla cacti, identifiable by their cone-shaped yellow fruits, might treat the eye with dazzling flowers of purple and magenta, even now, still, in mid-July.

And every summer, all across this impressive desert, Nuevomexicanos, homesteaders, Mescalero Apache, and other Indigenous peoples eagerly await the rains. They’ll capture and store the concentrated downpours in open air cisterns. And that precious water will be used for drinking, bathing, and gardening. It’ll quench the thirsts of their goats, cattle, and sheep.

In addition to the rains, July also brings the year’s hottest temperatures; average highs in the Tularosa Basin approach 100 degrees Fahrenheit. Early mornings, though, are comparatively pleasant—in the mid-60s, on average. And so, even though it is still very dark, and very quiet, many people in the Tularosa Basin are already awake, preparing coffee, feeding their animals, or hanging their laundry.

On this morning, eleven-year-old Henry Herrera is outside, filling the radiator on his father’s Model A Ford11, and his mother’s laundry is about to be covered in radioactive fallout.

Seventy years from now, in July 2015, Henry will will recall this morning on an episode of PBS NewsHour.

“It was just black, black, real, real fine dust,” he says, “because momma had just hung up her clothes, white sheets and pillowcases and all the white clothes that she washed first”12.

I first learned about Henry in Joshua Wheeler’s 2018 book Acid West, a collection of essays about southern New Mexico, where Wheeler’s family has lived for seven generations. In the book’s second chapter, “Children of the Gadget,” Henry is a sort of main character, a charismatic and very funny guitar virtuoso and Tularosa legend who witnessed the world’s first nuclear bomb. Henry passed away in 2022, at the age of 87. He’d beaten cancer three times.

Mainstream narratives describe the Tularosa Basin as remote and uninhabited. Adding to that perception is the oft-referenced, foreboding name that Spanish conquistadors gave this particular stretch of the Chihuahuan desert: Jornada del Muerto, or journey of the dead. It’s catchy.

But Henry’s family lives just fifty miles southeast of this place we’re standing now, where, rising one hundred feet from the desert floor into the black sky is a steel tower, manufactured by the Blaw-Knox Company of Pittsburgh, who shipped it to New Mexico in parts. Ted Brown's Construction Company, out of Albuquerque, was contracted to put it together here.

They poured four concrete footings, each twenty feet deep and spaced thirty-five feet apart, to secure the massive tower’s legs. Cross struts climb to a platform built from oak, with an access door at the bottom, walled on three sides by sheets of corrugated iron. It looks like an exaggeratedly large guard tower from some futuristic prison.

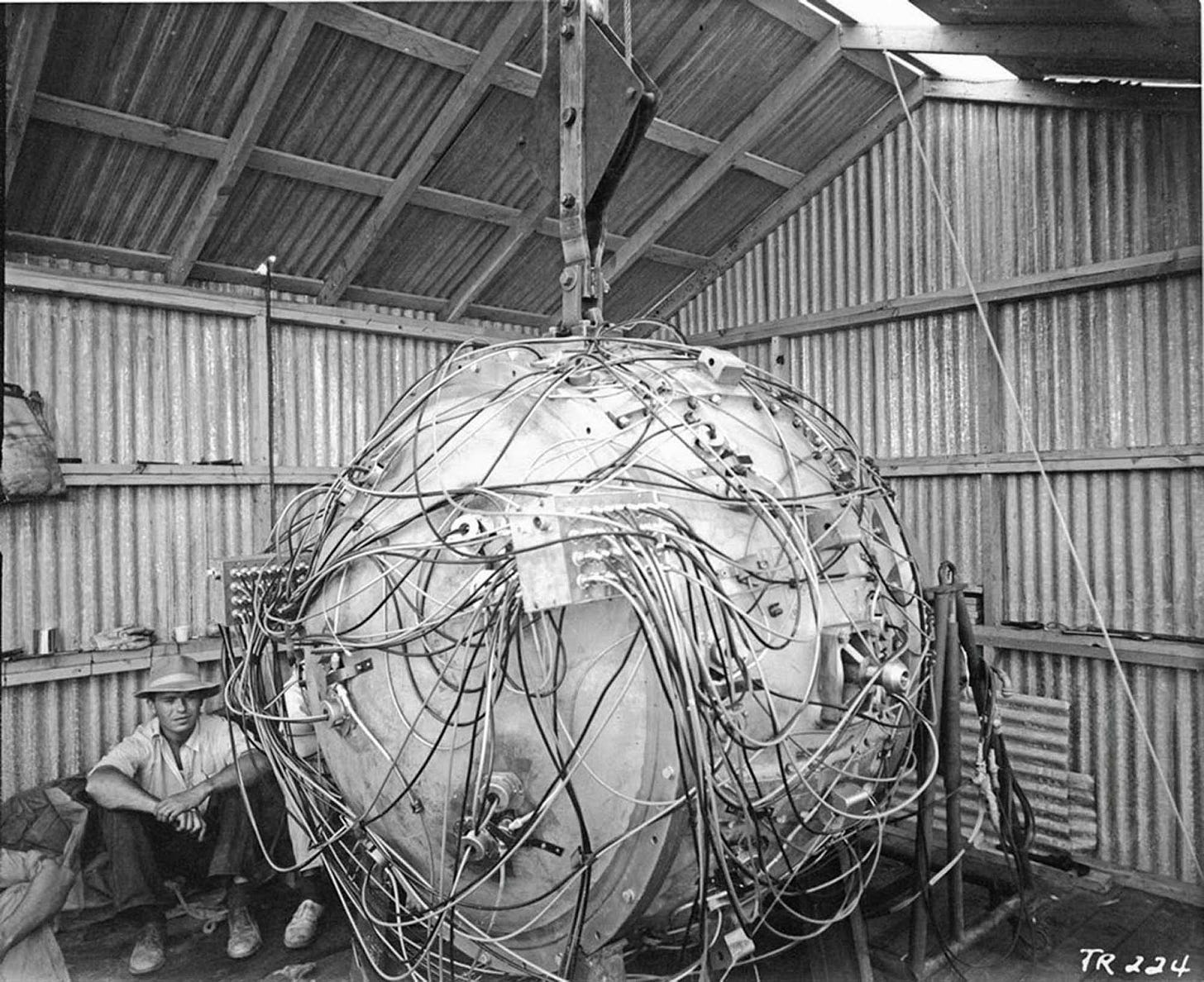

Dangling atop the tower is a 4-ton spherical handmaiden of death. The world’s first nuclear bomb.

The US military, who are about to detonate this weapon, would be happy for you to believe that this desert is empty. And in the eighty years since, that’s been their narrative. But the 1940 US census—taken just 5 years ago—listed some 13,000 residents living within 50 miles of this steel tower.

These are people who are uniquely poised to be poisoned by radioactive fallout. They grow their own food and raise their own livestock. They build their homes using local materials. The landscape is not an abstraction to them.

Henry Herrera and his family. Mary Martinez White’s family. Thousands of families.

At the park in Santa Fe, Mary recounted the first time she truly considered the generational impacts of the Trinity detonation.

“I was working in Socorro, with the courts at the time, and expressing to a colleague that mother was dying of cancer. And she says, ‘Well, you’re a downwinder.’

And I’m like, ‘What’s that?’

And she says, ‘Well, haven’t you heard of the downwinders of Utah and Nevada because of the Cold War? You’re a downwinder from Trinity.’”

Over the last two years, the bomb now suspended above us was designed and engineered in total secrecy about 200 miles north of here at Project Y, atop the Pajarito Plateau, overlooking Santa Fe. In charge of Project Y are physicist J Robert Oppenheimer and General Leslie R Groves.

You probably know Project Y as Los Alamos National Laboratory.

Project Y is the central node of the Manhattan Project, the US military’s yet-undisclosed but geographically, financially, and intellectually massive effort to exploit the nuclear properties of a naturally occurring chemical element called uranium.

In 1938, German physicists discovered that they could split an atom by bombarding it with neutrons. Almost immediately, physicists around the world understood the implications: a nuclear chain reaction of this sort could be used to create a weapon of mass destruction.

One year later, in 1939, after being convinced by Hungarian scientists Leo Szilard, Eugene Wigner, and Edward Teller—all of whom had recently fled Europe—that the Nazis would undoubtedly pursue such a weapon, Albert Einstein penned an appeal to President Roosevelt, urging him to consider an American atomic program.

Within a few short years, an early nuclear reactor was built at the University of Chicago, physicists at UC Berkeley discovered how to enrich and exploit the radioactive qualities of uranium, and the Manhattan Project was born. Since the project’s inception, its goal has been to create a bomb whose explosion will burn hotter than the surface of the sun.

Los Alamos is the name of the officially nonexistent town adjacent to the Project Y laboratory. By 1945, the population of Los Alamos has swelled to over 8,000. This includes scientists, soldiers, officers, engineers, technicians, and their families.

To weaponize uranium, the military had to enrich it, a costly and complex process. This has required two additional massive Manhattan Project sites: Oak Ridge, Tennessee, where uranium-235 was separated out from the more prevalent uranium-238 isotope using calutrons developed at UC Berkeley, and Hanford, Washington, where plutonium was produced using a large-scale nuclear reactor.

Beneath the Hanford site in 2025, there are 177 storage tanks holding 56 million gallons of highly radioactive and chemically hazardous waste13—the byproduct of decades of plutonium production.

Situated on the Columbia River, which gives life to so much of the Pacific Northwest and provides a significant portion of Portland’s drinking water, Hanford is one of the most radioactive places on Planet Earth14.

This morning, in July of 1945, Oppenheimer and Groves are not planning to drop the bomb from its tower. Impact with the earth, they have correctly surmised, would dampen its destructive power. Atomic bombs are more effective when exploded over their targets—in what’s called an “air burst”—because this maximizes their blast radius by more broadly distributing the energy produced by the explosion.

Oppenheimer’s teams at Project Y have developed two models for the nuclear bomb.

The original design is what’s called a gun-type device, where a 7-inch, 80-pound hollow “bullet” of uranium—enriched at Oak Ridge—is shot down a barrel at target: a solid uranium cylinder. The collision produces a burst of neutrons and a critical chain reaction. Three weeks from today, we will explode one of these, nicknamed “Little Boy,” over the Japanese city of Hiroshima.

The other design is a plutonium-implosion device, which uses two hemispheres of plutonium—produced at Hanford—to create what's called the pit. About the size of a grapefruit, the pit is surrounded by explosive lenses that detonate simultaneously, compressing it to produce a nuclear chain reaction. Three days after Hiroshima, on August 9, 1945, we will explode one of these, called “Fat Man,” over Nagasaki.

Between Nagasaki and Hiroshima, more than 200,000 people will die, a majority of whom are civilians15.

But first, we’re going to detonate this bomb, a plutonium-implosion device nicknamed “the Gadget.”

Developing the Gadget has cost some $2 billion in appropriated taxpayer funds16—the equivalent of $34 billion in 2025, larger than the GDP of Iceland. Yet the device is deceptively DIY and cartoonish-looking: bulbous, covered in patches of tape with wires protruding.

The Trinity explosion is commonly referred to as a test. But calling Trinity a test is, essentially, a lie by omission. The same goes for the thousand-plus weapons the United States military exploded at the Nevada Test Site and in the Marshall Islands throughout the latter half of the 20th century.

Detonating a nuclear weapon is detonating a nuclear weapon.

And the Gadget will be especially dirty. Even though it will be an air burst, it is still only 100 feet off the ground, meaning that the explosion that it is about to produce—the equivalent of detonating 21,000 tons of TNT—is going to suck up and redistribute a jaw-dropping amount of irradiated physical surface material.

Further complicating things: of the 13 pounds of plutonium that make up its pit, only about 15% is going to properly fission. The other 85% will be temporarily vaporized by the detonation’s immediate fireball (which will be so hot that it will turn parts of the Chihuahuan desert into a new type of glass called trinitite17).

Because it is monsoon season, that unfissioned, catastrophically deadly plutonium, as well as all that irradiated ground material, is going to get hurled around by rain and wind, and then deposited back onto the earth everywhere that rain and wind can go.

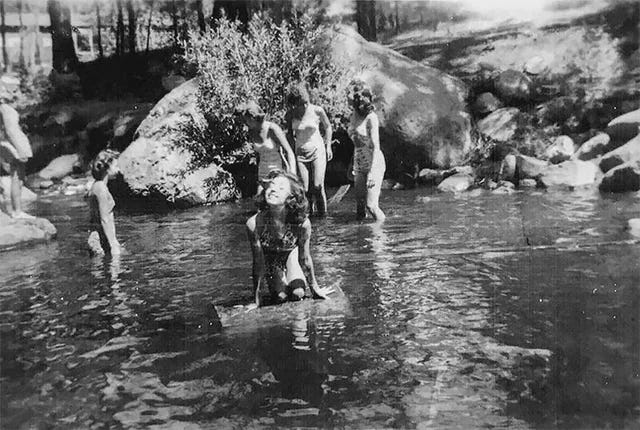

Trinity fallout will blanket a girls summer camp in Ruidoso, New Mexico, with ash that looks like snow. The dozen campers will rush out to see the extraordinary material, catching it on their tongues and rubbing it into their faces18. Ten of the twelve will die before the age of 4019.

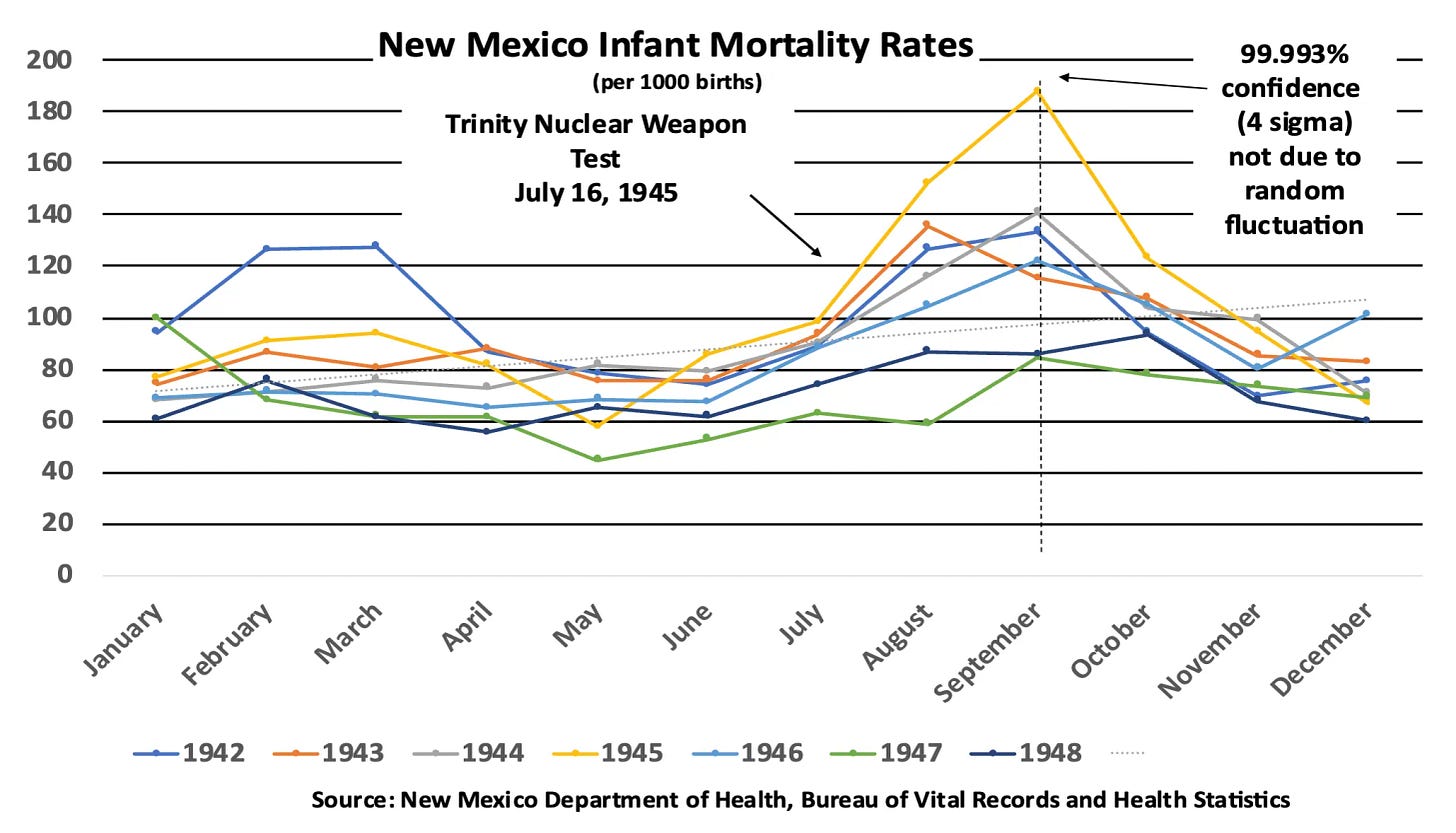

In surrounding counties where Manhattan Project personnel measure fallout, infant mortality rates will increase by an average of 21%, despite trending downwards in prior years. In Roswell, infant mortality rates are about to increase by 52%20.

Statistics can feel like abstractions, so let me be clear: we are talking about people helplessly watching their babies die from exposure to radioactive fallout. But they don’t know that’s why their babies are dying, because you can’t see radiation. And because no one will tell them.

In a couple of years, Kathryn S Benhke, a medical care provider in Roswell, will write to Stafford Warren, the radiation safety chief of the Manhattan project, telling him: “As I recall, in August 1945, the month after the first bomb was tested in New Mexico, there were about 35 infant deaths here”21.

Warren’s medical assistant, Fred A. Bryan, wrote Behnke a couple months later, saying that officials could find “no pertinent data” that would suggest that Trinity contributed to infant deaths22.

As we learned in Time Zero’s first installment, the half-life of plutonium is 24,000 years—about the amount of time that it has been since those ancient humans walked with mammoths, when this corridor of the Chihuahuan desert was a lake.

In fact, because the byproducts of nuclear weapons and energy production are beyond human scales of time by orders of magnitude, our nuclear imprint is about to become global and geologic in scale.

Seventy years from now, an international group of scientists will propose that the objectively measurable, planetwide persistence of radionuclides from atomic blasts be used to mark the dawn of the Anthropocene epoch23, the point at which human beings became “a geophysical force on a planetary scale”24.

All of this is to say that you don’t need to have been right near the Trinity blast, or even alive at the time, for it to give you cancer.

Besides embedding itself into the landscape, waterways, and local architecture, radiation physically mutates DNA, leading to intergenerational effects.

In July 2023, Trinity Downwinder Tina Cordova spoke with Russell Contreras on an episode of New Mexico in Focus on the state’s PBS station.

“In my family, I’m the fourth generation to have cancer since 1945. I had two great-grandfathers alive at the time who died in 1955 from what was described as stomach cancer. We’ll never fully know, because there was no treatment. They gave them morphine and sent them home to die. Both my grandmothers had cancer. My dad died from cancer after having two very distinctly different oral cancers that he didn’t have risk factors for. He didn’t drink excessively, he didn’t smoke, he didn’t use chewing tobacco, had no viruses. He developed two primary oral cancers. I had thyroid cancer. The first question they asked me was, When were you exposed to radiation?’”25

Three days ago, before sealing this unwieldy, science-fictional Gadget and hoisting it to the top of this 100-foot tower, a team of Manhattan Project scientists assembled the weapon’s plutonium core two miles south of here at the McDonald Ranch House.

The McDonald family had been vacated by the government—under protest—three years earlier to make way for the Alamogordo Bombing and Gunnery Range26, since renamed White Sands Missile Range. The scientists elected to put the finishing touches on the plutonium pit in the most personal part of the McDonalds’ stolen home: the bedroom27.

In 1962, General Groves wrote a letter to Oppenheimer, asking about the decision to codename their 1945 detonation in the Tularosa Basin “Trinity.” Oppenheimer replied that he’d conjured the name from the metaphysical verses of English poet John Donne, citing two of Donne’s works: “Hymne to God My God, in My Sicknesse” and “Batter my heart, three-person'd God”28.

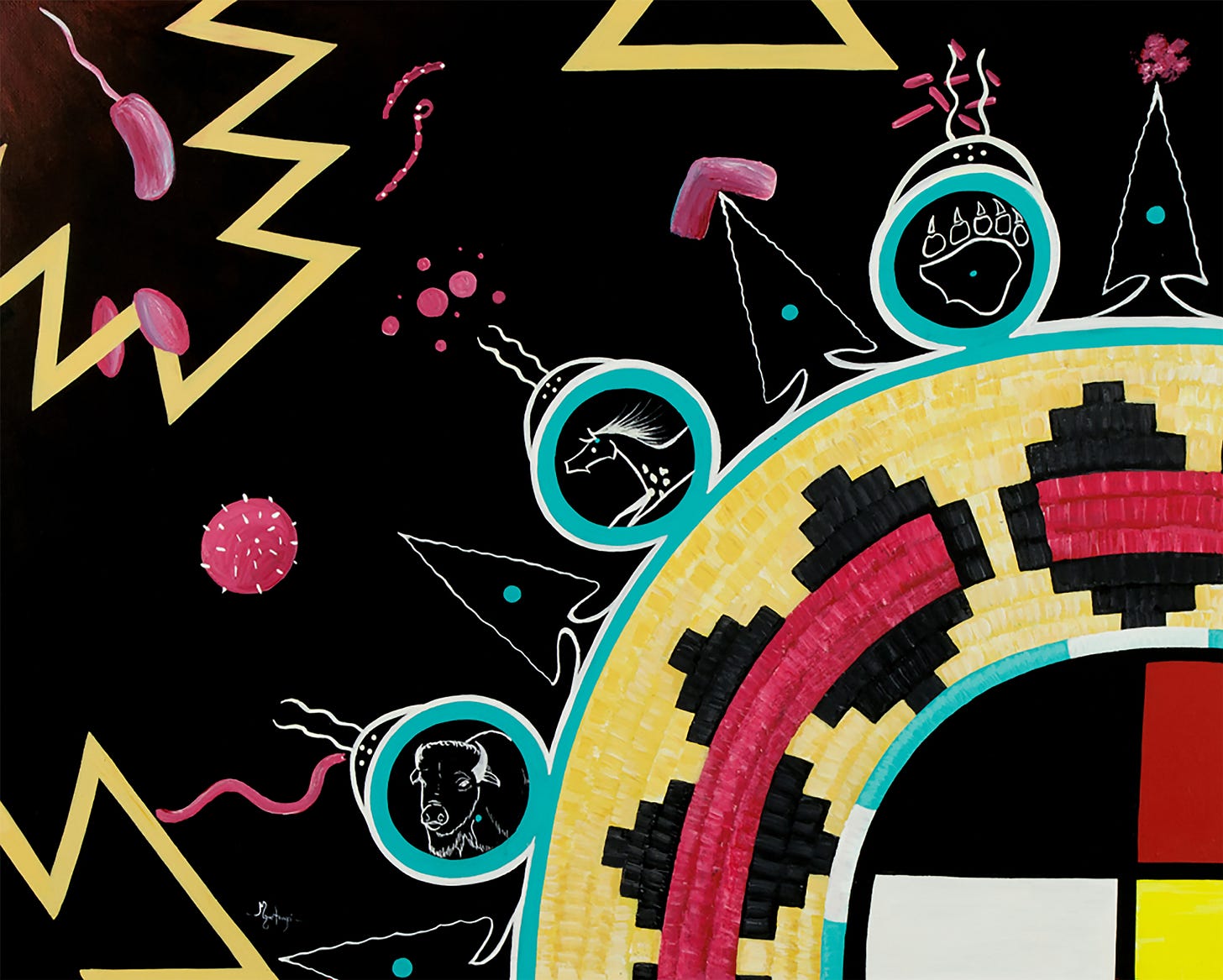

In May of 2024, artist Joanna Keane Lopez, who was born and raised in New Mexico, presented an installation at Stanford University’s Art Gallery, named after Donne’s poem, that considered atomic intrusions into domestic space.

At the center of the installation, titled Batter my heart, three-person’d God, was a twin-sized bed, its simple but elegant frame fabricated from ponderosa pine. The head and footboards featured vertical slats with triangular teeth pointed outward. They looked like stylized mountain peaks, or gamma waves, giving either end of the bed the appearance—from certain angles—of a meat tenderizer.

Behind the bed stood a wall that Keane Lopez constructed from adobe bricks, a craft she learned from generations of artists in her community back home in New Mexico.

Atop the bed sits a quilt, fashioned from churro wool and linen, with naturally dyed Colcha embroidery tracing the fallout patterns from the Trinity detonation. At the bottom stand three figures: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost.

I spoke with the artist by phone in October 2024.

“I was really wanting to approach the history of what happened at Trinity by thinking about this bedroom in the ranch house, where the plutonium core of the bomb had been constructed—thinking about the bedroom as this place of love, and death, and sex, and birth, and intimacy, and domesticity. And how that’s literally where they chose to almost begin the nuclear age. Where is this line between domestic space and the US military complex, and the nuclear industry, when domestic space and civilian life are just invaded?

Joanna Keane Lopez grew up with anti-nuclear activists for parents. Her late mother, journalist and filmmaker Colleen Keane, directed the 1987 documentary The River That Harms, about the 1979 Church Rock uranium spill, and later served for years as a correspondent for The Navajo Times.

The artist’s father, Damacio A Lopez, is director of the International Depleted Uranium Study Team, a non-governmental organization of researchers, activists, and scientists dedicated to stopping the use of depleted uranium in military weapons and in commercial products. In the 1970s, New Mexico Tech started testing depleted uranium weapons next door to the Lopez family’s ancestral land near Socorro, New Mexico29.

By that time, Damacio A Lopez already had a long history with the nuclear industry. He writes as much in this passage from a forthcoming autobiographical account of a life spent fighting nuclear colonialism in New Mexico and beyond.

“I was nearly two-years-old on July 16, 1945, when the world's first atomic bomb was detonated just 35 miles from my ancestral home.

Many people in Socorro, New Mexico, woke up to broken windows and cracked brick and adobe walls, unaware that the cause was a nuclear bomb that had exploded in their backyard, at just 5:30 a.m.

In time, people referred to the event as the Day the Sun Rose Twice.”

The contamination of the Lopez family’s ancestral land has violently darkened Joanna Keane Lopez’s relationship to the local-materials-focused adobe architectural practices she’s been trained in.

Who wants a home built out of irradiated earth?

In less than one second, a trigger will set off 32 explosive lenses to begin the Gadget’s nuclear chain reaction. The converging shock waves will generate pressures inside the bomb that are 500,000 times greater than the earth’s surface air pressure. Within millionths of a second, space and time, as we understand them, will be torn open.

A few physicists have become concerned by Edward Teller’s recent calculations suggesting that there is a non-zero chance that a nuclear explosion could set fire to the atmosphere. What this means is that the chance is not expected, but also cannot be confirmed as zero. After some serious reviews and deliberation, Manhattan Project scientists are now reasonably sure—we’re talking 99.99% sure—that this detonation will not ignite the earth’s atmosphere. Technically speaking, though, they cannot be entirely sure.

Physicist Emilio Segrè, who headed the Manhattan Project Radioactivity Group, will recount this situation in a 1983 interview with American historian and journalist Richard Rhodes, author of The Making of the Atomic Bomb30.

Segrè: I asked and informed myself whether they were absolutely sure that the atmosphere wouldn’t catch fire. They assured me what they had done, so, but you know. I mean, they can always make a slip. That thing was pretty fearful. So, I mean, I can’t say that I started to calm down!

Rhodes: There’s the story about Fermi joking about igniting the atmosphere the night before, upsetting General Groves, or something.

Famously, since last night, physicist Enrico Fermi has also been taking bets on whether this will occur.

Segrè: People had calculated all the mass defects, all the packing fractions, and everything that one knew. And making all of the hypotheses, possible hypotheses, came out, and there was no chance of igniting the atmosphere. But I’m enough of a physicist to know that you calculate everything, and then something happens that you never dreamed of.

This morning’s original blast time of 0400 hours was called off because of the storms. Physicists cautioned that lightning could trigger an early detonation and that high winds and moisture could impede their ability to accurately capture data and footage of the explosion. Further, they speculated—quite correctly—active rain, would more dangerously distribute fallout and radiation31.

You might, understandably, be asking yourself: won’t the detonation of an atomic bomb, even in the most optimal of weather conditions, dangerously distribute fallout and radiation?

Of course it will.

Still, rain will indeed make it that much worse, because all those invisible plutonium particles floating through the atmosphere in that radioactive cloud will get slammed back down to earth in higher concentrations. Just days ago, Manhattan Project meteorologist Jack Hubbard, frustrated over the military’s insistence on the July 16 detonation deadline, vented into his diary: “[R]ight in the middle of a period of thunderstorms. What son-of-a-bitch could have done this?”32

Why don’t they just wait a few weeks until the weather is more predictable? Germany surrendered more than three months ago. Japan is on the ropes.

The test has to happen this morning, July 16, 1945, because President Harry S Truman is about to attend a conference at Potsdam with Soviet leader Joseph Stalin and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. They’re going to be discussing how the Allied Powers will be dividing up Germany. It will be extremely productive for the United States if Truman can intimidate Stalin with news that we’ve successfully developed and detonated the world’s first nuclear bomb.

What Truman doesn’t know, however, is that Stalin already knows about the bomb. In fact, thanks to Soviet espionage, Stalin has likely known about the bomb for three full years—far longer than Truman himself, who was only filled in back in April, after Roosevelt died unexpectedly, and Truman, his VP, suddenly found himself President of the United States at the apex of the Second World War33.

Adding to the manufactured urgency is the fact that Truman has been demanding unconditional surrender by the Japanese, which has, according to many historians, been dragging out the conclusion of the Pacific Theater far longer than is necessary.

Truman wants hard confirmation that the bomb works so he can lay waste to the island of Japan.

In early June of 1945, Truman sent a special message to the US Congress34, which he also adapted for a news reel.

“Substantial portions of Japan’s key industrial centers have been leveled to the ground in a series of record incendiary raids…

What has already happened to Tokyo will happen to every Japanese city whose industries feed the Japanese war machine…. We have no desire or intention to destroy or enslave the Japanese people. But only surrender can prevent the kind of ruin which they have seen come to Germany as a result of continued, useless resistance.”

When Truman issued this warning weeks ago, was he hinting at the bomb? Perhaps. But until this exact moment, nobody knew for sure whether the atomic bomb would actually work.

About forty-five minutes ago, physicist Kenneth Bainbridge—who is technically in charge of this detonation, under the direction of Oppenheimer—received word from meteorologist Jack Hubbard that the skies would clear between 5 and 6 a.m.

And they did.

So, here we are. July 16, 1945.

05:29 a.m. Mountain War Time.

The military and science men are in their bunkers or at their appointed stations, wearing protective lenses. Physicist Edward Teller has slathered his face in zinc oxide. New York Times reporter William L. Laurence, who will also ride along on the Nagasaki bombing—and later collaborate for years with the Atomic Energy Commission to publish nuclear propaganda in the paper of record3536—has his notepad at the ready. The detonators are fully charged.

Henry Herrera’s mother has just hung up her laundry. Eight-day-old Bernice Gutierrez is likely fast asleep, as is Joanna Keane Lopez’s two-year-old father, Damacio, and the dozen girls at summer camp in Ruidoso.

Over loudspeakers, the silence is interrupted.

10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1…

When Christopher Nolan’s blockbuster Oppenheimer hit the theaters in summer 2023, the Trinity Downwinders were disappointed, but not surprised, that the film never so much as mentioned the thousands of people living near the blast site.

Even with eighty years of hindsight, and even though Tina Cordova and others have appeared before Congress, the populations who live in and around the Tularosa Basin were an inconvenience to Nolan’s tortured genius narrative.

There are two very brief mentions of the potential aftermath of this so-called “test,” and seemingly one single reference to the actual landscape surrounding the Trinity site.

At 01:45:56 into the film, Benny Safdie’s Edward Teller raises a question that’s quickly brushed aside by Cillian Murphy’s J Robert Oppenheimer.

Teller: What about the radiation cloud?

Oppenheimer: Without high winds it should settle within two to three miles. Evacuation measures will be in place, but we need good weather for visibility so it has to be fine37.

Again: it is July. Monsoon season. Good weather can, under no circumstance, be guaranteed. And nobody was evacuated.

Three minutes later, Oppenheimer off-handedly mentions White Sands by name.

Oppenheimer: If we fire those detonators and they don’t trigger the reaction, two years’ worth of plutonium will be scattered across White Sands38.

The concern expressed here is, without question, for the plutonium, not the people.

And because of such obfuscations, the audiences who flocked to see Oppenheimer could be forgiven for thinking that Trinity was detonated at some mythological empty expanse adjacent to Los Alamos. It’s quite possible that most people involved in the film had little to no understanding of the geography of New Mexico. Take this promotional appearance by members of the cast on Jimmy Kimmel’s late night show.

Kimmel: Where did you shoot the movie? What area did you shoot most of the film?

Murphy: Eh, it was all around. We shot a lot in New Mexico around Los Alamos where the actual Trinity test happened39.

Maybe you’re inclined to give Cillian Murphy the benefit of the doubt here—that “around Los Alamos” could encompass the Tularosa Basin, some two-hundred miles to the south. But if that’s what he meant, it’s unfortunate, because it echoes centuries of colonial flattening of the geographically and culturally diverse Southwest into a generic mono-desert.

It is exactly this type of glossing over of the populations in and around the Trinity explosion that has produced eighty years of righteous anger.

Consider this: the distance between the Trinity Site and Los Alamos is almost as far as the distance between Murphy’s birthplace of Cork, Ireland, and the British colony of Belfast in Northern Ireland. We can imagine that Murphy would draw a pretty firm distinction between those places.

Of all the genres of white people, you’d hope an Irishman would be a little more sensitive to this stuff.

With Oppenheimer, Christopher Nolan had a unique opportunity, on a massive scale, to introduce millions of theatergoers to the Trinity-affected people of central-southern New Mexico. But across all three gluttonous hours of Oppenheimer’s runtime, Nolan couldn’t even bother with a single sentence of dialogue, or a one-second shot of a rancher, outside at 5:29 a.m., turning to look at the brightest burst of light that anyone had ever seen.

I saw Oppenheimer in IMAX, the day it was released, in El Paso, Texas, a downwind city and the closest IMAX to the site of the Trinity detonation. The next morning, 90 minutes north in Alamogordo, New Mexico, the military (and downwinder) town adjacent to White Sands, I got coffee with Joshua Wheeler, the author of the 2018 essay collection Acid West, where I’d first learned about Henry Herrera and the Trinity Downwinders. Wheeler was back home visiting family during summer break from his teaching job in New Orleans. We talked about our impressions of the film, especially our shared conclusion that audiences would likely be misled about the location of Trinity.

When we parted ways, I headed to Roswell to link up with a friend, Alex Boeshenstein, whom you’ll meet later in a later installment of Time Zero (and who kindly lent several photos to this text). Josh headed home to lock into what was going to be an afternoon of interviews about Oppenheimer. His writing on New Mexico—especially its nuclear histories—had made him a go-to commentator for newspapers, magazines, and other media.

A few hours later, in Roswell, my phone alerted me to an email. It was Josh.

“A reporter who watched the film,” he wrote, “just stopped in the middle of an interview and asked, ‘So wait, the bomb was not tested at Los Alamos?’”

For the highly anticipated Trinity scene in Oppenheimer, Christopher Nolan’s massive budget allowed the director to task special effects teams with recreating an actual explosion, only later using computer technology to layer the filmed imagery.

During a press push in early 2024, Nolan appeared in a pre-taped interview on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert.

Nolan: The Trinity test had to be threatening, it had to be incredibly beautiful. But also, you know, primally threatening. And analog imagery is just a lot better at doing that.

Colbert: So, how’d you do it?

Nolan: They did a lot of very large explosions, but with forced perspective, so they would appear bigger than they were, with varying frame rates40.

Upon the film’s release, plenty of ink was spilled praising Nolan’s analog approach, and his choice to leave the scene largely silent, save for characters’ heightened breathing as they stare at the blast through protective lenses until, in voiceover, Oppenheimer recites his famous quote from the Bhagavad Gita, “And now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.”

And then, the sound of an enormous explosion.

That sonic delay was true to life. It is estimated that it took between 30 and 40 seconds for the physical shockwave and accompanying sound to reach Oppenheimer, Groves, and other observers stationed at 10,000-yard distances to the north, west, and south of Ground Zero41.

There was something unique about sitting in near-silence in a sold-out cinema for close to a full minute—a sort of truncated John Cage piece.

The entire time, though, I couldn’t help but feel, to put it kindly, underwhelmed by Nolan’s IMAX spectacle depiction of Trinity.

This has almost nothing to do with how convincing or unconvincing the explosion was. What troubled me was a total absence of the artistic gravitas that representing such a horrific moment demands. After the bomb, the only lingering darkness is Oppenheimer’s emergent guilt, despite the fact that, within hours of the detonation, morning rainstorms dumped airborne plutonium all over the 13,000 residents living within that 50-mile radius.

I realize that the film is called Oppenheimer, but come on. The outcomes of that explosion are so much more complex, and so much more compelling, than Oppenheimer’s Bruce Wayne-ification, getting disillusioned into becoming Batman or whatever.

And seemingly, Nolan got so fixated on showing us both sides of the bomb—its threatening aura and, in his own words, its beauty—that he got lost in the aesthetics.

A far more harrowing—and, I’d argue, spiritual—depiction of Trinity appears in part eight of Twin Peaks: The Return, David Lynch’s 18-hour coda to the original series, released a quarter of a century later.

Lynch’s black-and-white sequence begins with an inky, wide shot of the Tularosa Basin. We are drenched in that darkness. Text appears on the screen, line-by-line, firmly rooting us geographically and chronologically.

The sounds of the desert winds are pierced by the staccato of the countdown, and then, a flash of light. The blinding white dissipates, revealing a digitally animated mushroom cloud rising into the sky. The Tularosa Basin is lit up in eerie grays.

From miles away, hanging in the sky, the camera begins an achingly slow zoom towards the expanding radioactive burst. Punishing the ears is “Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima,” a 1961 string arrangement of skin-peeling cacophony by Polish composer Krzysztof Penderecki. The screeching sonics hauntingly link the local victims of this moment in space and time with those of the near future across the Pacific Ocean in Japan.

The music seeps into your marrow, like the plutonium particles raining down all over homes occupied by Damacio A. Lopez, the families of Tina Cordova and Mary Martinez White, and thousands of others living on ranches or in Alamogordo, Ruidoso, or on the Mescalero Apache Reservation.

Eventually, Lynch completely collapses the distance typically afforded by imagery of nuclear weapons explosions. Through the camera’s dive, we cross into the churning fallout itself. Recognizable imagery gives way to six grueling minutes of experimental, abstract color blocks, glitching static, and seizure-inducing light scribbles.

Watching The Return, part eight, the night the episode premiered in 2017, all I could think was, “I cannot believe that this is on American television.”

In the last episode, we talked about Lynchian aesthetics, where violence and darkness simmer beneath the banality of everyday Americana. And while Trinity was patently American, there is absolutely nothing banal about it. And Lynch knew this.

Thus, his articulation of the event is not Lynchian, in the classic sense. Rather, it portrays the precise moment—time zero—that birthed the cultural conditions for Lynchian aesthetics.

The emergence of the nuclear bomb and subsequent postwar economic boom it helped to produce brought material comfort and tranquility for certain Americans—predominantly white suburbanites. Simultaneously, as the US continued exploding bombs in the Pacific Ocean and in Nevada, untold numbers of Marshallese and Americans were irradiated. The number of deaths that resulted from this radiation is impossible to accurately quantify.

And across the world, every single person was subjected to a new kind of existential terror: nuclear holocaust. That terror, in concert with American petro-colonialism, underpinned the seeming stability of midcentury America that Lynch’s films (and Twin Peaks’s first two seasons) so effectively satirized.

In Nolan’s biopic, we learn that the Trinity bomb engendered ambivalence in J Robert Oppenheimer.

In Twin Peaks: The Return, we learn that Trinity birthed Lynch’s most infamous villain, BOB, a manifestation of pure evil, setting in motion the events of the original television series.

What’s more, Lynch's fiction soberly points to nuclearisms’s insidious, multispatial and multitemporal consequences, which have redefined both the American project and all human life since.

Following Twin Peaks: The Return, there has been internet fan speculation about BOB’s name.

In the original series, the clues that BOB leaves on his victims spell out Robert. The character Leland Palmer, to whom BOB appeared in his youth, knows him as Robertson. The suggestion being that if BOB was birthed by Oppenheimer’s Trinity detonation, he might be J Robert’s son: Robert Jr, the diminutive for which is, of course, BOB.

Other fans have counterpointed that BOB is named after the all-American diner chain where Lynch was known to religiously eat cheeseburgers for lunch: Bob’s Big Boy.

Regardless of BOB’s name, the point is that Lynch’s depiction, which employs abstraction, dissonance, and dislocation, offers a terror that Nolan’s budget, scale, and fidelity does not. This somewhat counterintuitive principle—where you don’t need spectacle to terrorize your audience—is well-documented in horror cinema: Psycho, The Blair Witch Project, Evil Dead. The list goes on.

In our last installment, we met anthropologist Joseph Masco, author of The Nuclear Borderlands (2006) and The Future of Fallout (2020), who coined the term nuclear uncanny. In speaking with communities who lived near nuclear facilities, Masco encountered multiple instances where the invisible presence of radiation and the ongoing threat of nuclear apocalypse produce a feeling of dislocation and paranoia.

Dislocation and paranoia run rampant through Twin Peaks: The Return, and I am particularly interested in Lynch’s depiction of Trinity as far more than a singular, localized event. So, when I spoke with Masco in July 2024, after we’d warmed up a bit, I asked him if he’d seen it. He most certainly had.

“We don’t even have good vocabularies for talking about event structures that last, you know, on the scale of decades and millennia. And to really take responsibility for releasing those kinds of event structures would really change the nature of our politics, and you could not have a concept of national security based in nuclear nationalism. That would just fall away immediately. So there’s all sorts of mechanisms and intentionality in preventing that brain from emerging. So, what Lynch was doing in that episode was quite important, I think, because it offers a new vocabulary and some new ways of thinking about the Trinity test.”

A week before Oppenheimer was released, I was in Las Cruces, New Mexico, for that exhibition I mentioned earlier, about the legacies of Trinity, that was organized by Tina, Mary, and the rest of the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium.

They’d brought on Marisa Sage and Jasmine Herrera of the New Mexico State University Museum of Art to jury the open call. Sage and Herrera ultimately selected seventeen artists, from within and outside New Mexico, working in a variety of disciplines. What tied their diverse practices together were their sharp critiques of the way that nuclear industries have so casually put certain populations—especially, in the American Southwest, Hispanic and Indigenous populations—at existential risk.

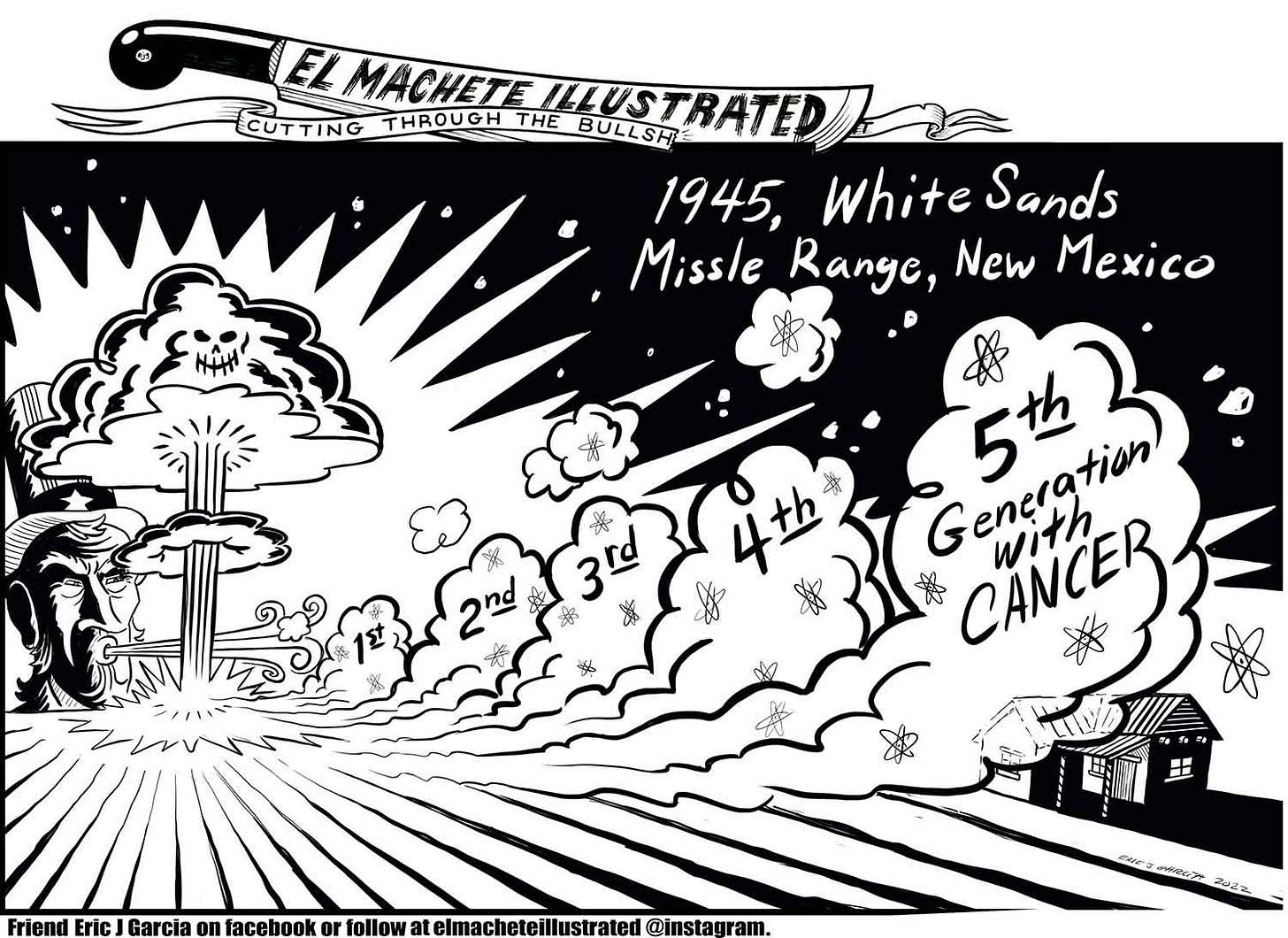

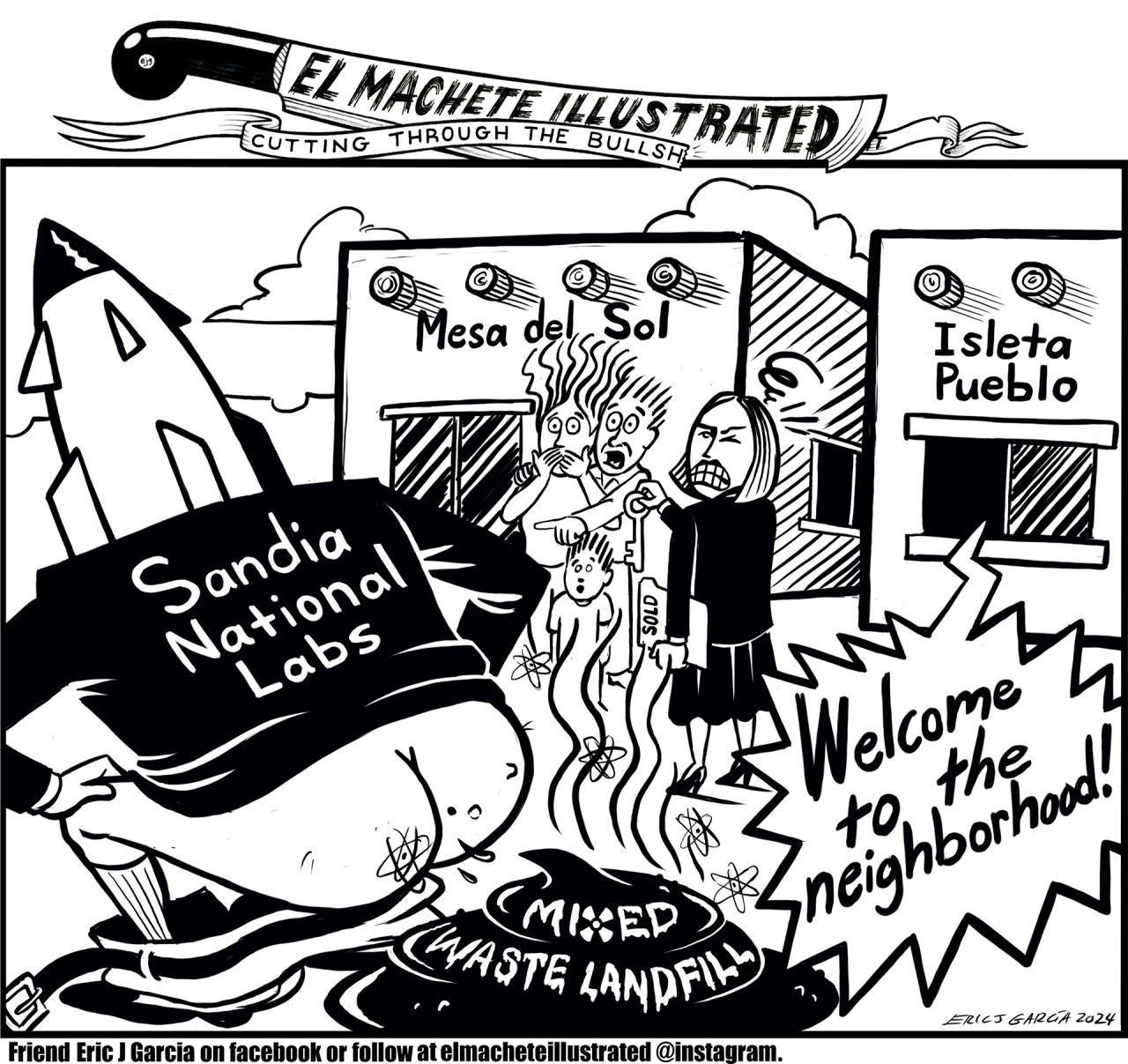

Hung high in the gallery was Albuquerque-based artist and political cartoonist Eric J. Garcia’s black-and-white drawing, Generational Blast from 2022, printed onto a large banner. In the piece, a cartoonish, grinning skull emerges from a churning cloud of plutonium particles, irradiated molten earth, screaming water vapor and shredded detonation tower debris. Thousands of feet below, behind the mushroom cloud’s roiling stem, Uncle Sam is blowing rhythmically, sending five toxic bursts over southern New Mexico’s Tularosa Basin. The farthest plume envelops a small ranch cabin. Above it, haunting text reads: 5th Generation with CANCER.

Other works in the show included Detroit-based Shanna Merola’s time-and-space-bending collages, and Zuni artist Mallery Quetawki’s paintings that use Indigenous iconographies to show the way that the human body interacts with radiation.

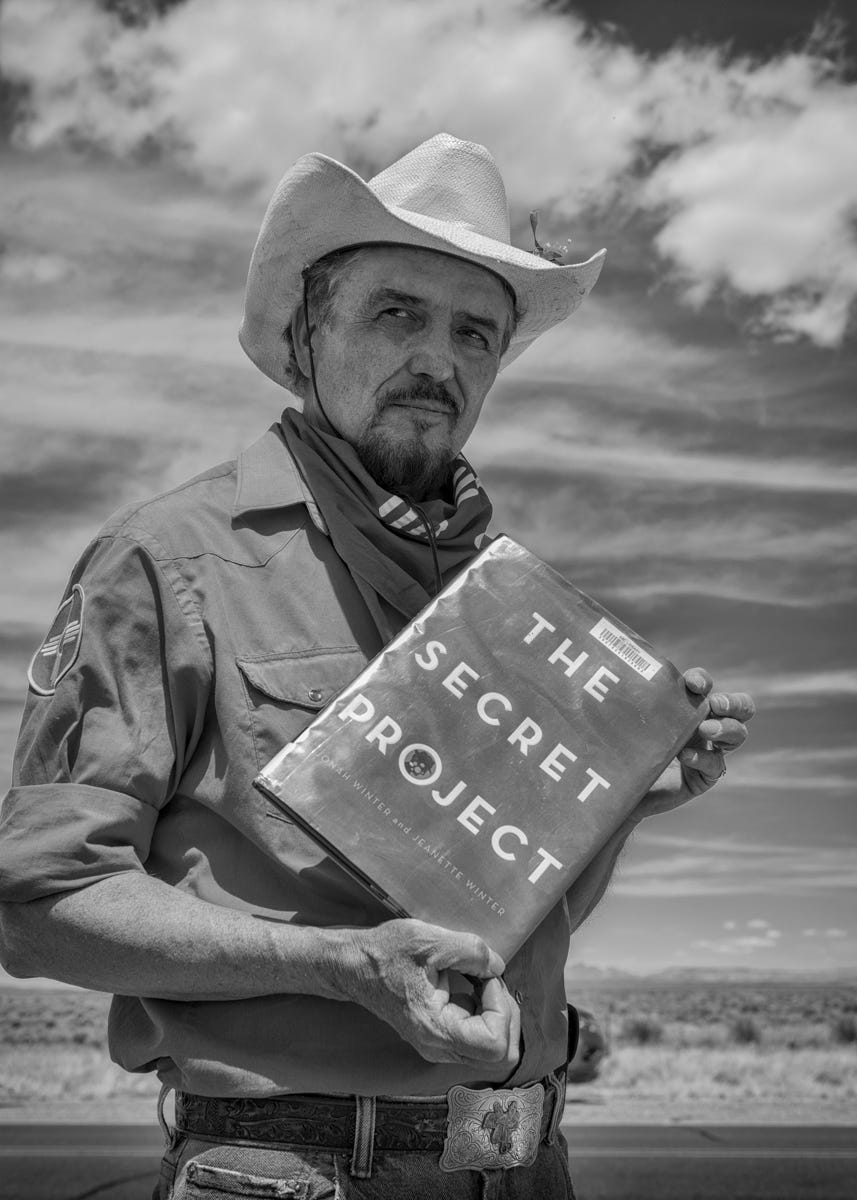

Los Angeles photographer Reto Sterchi, who’d also learned about Trinity’s victims from Joshua Wheeler’s Acid West, contributed arresting portraits of Trinity Downwinders, including Henry Herrera.

Emmitt Booher, a photographer based in New Mexico, showed images of the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium demonstrating outside of gates at the Trinity Site. Every April and October, thousands of atomic tourists from all over the world get the chance to see Ground Zero. Tina, Mary, Paul, and other downwinders are there to offer the unheard story of the world’s first atomic bomb.

Following the exhibition’s opening, people gathered at Albert Johnson Park in Las Cruces for the annual downwinders vigil remembering Tularosa Basin residents who have died from cancer since 1945. The vigil always happens on, or around, the anniversary of Trinity, and usually in Tularosa. They’d moved it to Las Cruces this year, to coincide with the art show.

They opened with the pledge of allegiance. Whenever I’ve spoken with them, the Trinity downwinders have made sure to clarify that they’re not anti-government.

“We love this place and we’re patriots,” said Mary Martinez White, as we sat in the park in Santa Fe the following summer. “And we’ve given our brothers and sisters. My dad, my brothers all served. My nephew, Martin Ray Barreras, was a command sergeant major, killed in Afghanistan. Special Forces. We love America.”

I suggested that, perhaps, they just wanted it to love them back.

“Yes, yes,” said Mary. “We want to trust our government.”

As the sun sank in Las Cruces, a field of 800 luminarias, one for each of the dead, glowed orange. Soon, charged purple thunderheads gathered. Distant lightning flashed. Monsoon season.

For over two hours, downwinders including Mary Martinez White, Bernice Gutierrez, Paul Pino and Tina Cordova read the names of the departed—names that span four generations now: Brusuelas and Montoyas. Camposes and Silvas. Pinos and, of course, Cordovas. It’s an intimate community, after all.

Earlier that day, Tina Cordova’s mother and aunt were at the exhibition’s opening. Her niece, MacKenzie Cordova, who grew up in Tularosa but attended college in California, was also there. She even had a piece in the show titled The Sun from 2020, which riffs on the tarot, featuring Tularosa’s St. Francis de Paula church, hummingbird skulls, and the Zia symbol. A mushroom cloud rises in the background.

MacKenzie’s piece hung across the gallery from Eric J. Garcia’s Generational Blast which, it turned out, was upsettingly prescient. The previous November, MacKenzie, who was 23 years old, had been diagnosed with thyroid cancer.

Eric J Garcia, the artist behind Generational Blast, has a complex history with atomic weapons.

I happen to be a US veteran and served in the United States Air Force. And my last year was here, in Albuquerque. So I have… it was a real… I don’t want to say privilege, but I had a firsthand experience of seeing things that no other Burqueño sees on a daily basis. I protected those damn weapons of mass destruction. And if people only knew what was behind the walls of Kirtland, it would astound you.

Eric’s referring to Kirtland Air Force Base, which sits directly next to Albuquerque’s public airport. Beneath Kirtland is the Underground Munitions Maintenance and Storage Complex, the largest nuclear weapons holding facility in the world. At any given time, there are between 2,000 and 3,000 nuclear warheads sitting underneath the city of Albuquerque42.

Albuquerque is also home to Sandia National Laboratories which, along with Los Alamos to the north and the Lawrence Livermore lab in California, is a central hub in US nuclear weapons development.

It was late June 2024, and Eric and I were on the patio of a busy coffee shop in Albuquerque. Before the art show in Las Cruces, where I’d first encountered his work, Eric had originally connected with the downwinders after he and his wife decided to drive down and join them at their protest outside of the biannual Trinity Open House.

“So, as you come in through the gate, to go into the White Sands Missile Range, you’ll see the downwinders there with their signs… and their presence to let people know that this was not just a simple test site, but that there were people actually affected by these tests.”

It’s likely that most of those tourists, arriving in a line of cars that snakes through the desert, are under the impression that the area is, besides the military, uninhabited. Seeing the downwinders demonstrating must be quite a surprise.

After Garcia and his wife got home from demonstrating that first year, he got a surprise of his own.

“And then, when I had told my brother—who is also a historian and an activist—that we were down there, he goes, ‘You know, we’re downwinders as well’. And I said, ‘What does that mean?’ And he said, ‘Take a look at the map, take a look at where that fallout went.’”

“And if you look at that map, right above White Sands Missile Range, and the county of Socorro…”

You’ll remember, that’s where Joanna Keane Lopez’s dad, Damacio, was living during the Trinity detonation.

“… and above that county is Torrance County, the home of both my parents, who are from the small little village of Torreon, New Mexico. So when that blast exploded, that first atomic bomb, all of that fallout contaminated not only the surrounding Tularosa Basin and White Sands, but it went north, right on top of Torrance County, right on top of the little town of Torreon.”

As Eric continued, his story sounded like so many of the stories I’ve heard from people living in New Mexico, Utah, Nevada, and Arizona, as what had always been explained away as just a bad roll of the genetic dice started to look very, very different in light of new information.

“So we were contaminated. That fallout did hit us. And I started thinking, like, my dad had had prostate cancer. My uncle Melton had prostate cancer. My uncle Abe, he died at 30 for some unknown reason. I started naming all these different uncles who had cancer and all these different illnesses, and I started thinking… I think there’s a reason there. I think there’s a connection. I don’t think it’s just a bad coincidence that all my family has had all these different illnesses. I finally put the pieces together. It finally just dawned on me.”

Eric wrote about these experiences in a blog post for Just Seeds in 2022.

And for anyone with relatives who were alive in 1945 virtually anywhere in the United States, this animation below, published in 2023 in the New York Times43, should demonstrate how truly massive of an event structure Trinity truly was.

And let us remember: they set off 67 more of these in the Marshall Islands, and then 100 in Nevada, before moving underground in the early 1960s.

Sitting across from Tina Cordova in Santa Fe in June 2024, the day after RECA expired, I asked her a question that people have been asking her for two decades now, because I needed to know. Because I want to have even a sliver of the courage that she does. So I asked her:

How do you, Tina, keep fighting the most powerful people in the history of the world?

“They talk about it in the film. It was my father and my mother, but my father really drove this with us. It was my father's life goal that we would never feel like we were inferior to anyone for any reason.

You know, this morning I exchanged text messages with somebody who was saying, ‘Stay strong, don't give up. We're counting on you. We believe in you.’

And I told them, ‘I'll be damned if I'm going to let them win.’

I really do believe if you believe in something, you have to believe that it can happen. There is a certain level of believing in things. If I had listened to everybody throughout my life that has said negative things, I wouldn't be here. I was a teenage mom. I'm a divorcee. I filed bankruptcy after the divorce because I had student debt that I couldn't pay. And I was a single mom. I started a business with $5,000 that's 34 years-old. And we're a multimillion dollar company. I started this organization 19 years ago when no one had ever even really heard the word downwinders in New Mexico and have now gotten to the point where I feel like we're playing chess with members of Congress, right?

People told me, ‘Oh, you'll never amount to anything,’ when I was a teenage mom. And I graduated in four years with a bachelor's degree and two years later with a master's degree. And I had a child. I worked part-time and went to school. I was the dorm mother. I mean, I did everything I had to to succeed.

If you don't believe something's going to happen, it's not going to happen for you. I mentioned last night that I have an aunt that I talked to this week and she said, ‘Stop doing this. You're going to kill yourself. It's taken you away from us. It's taking you away from life. You need to get on with your life and forget about this.’

And I told her, ‘I'll be damned if I'm going to lose this one. I'm not going to lose this one. And I know the day is going to come. I know it just as sure as I know the sun's coming up tomorrow.

Last night somebody told me that I reminded them of Dolores Huerta. I like that better than Erin Brockovich.’

I'm not going to ever stop.”

If you’ve enjoyed Time Zero and want to support my research, you can subscribe below (or upgrade to a paid subscription).

If there’s anyone you think might be interested in Time Zero, please share.

Nevada National Security Site. “Camp Desert Rock.” PDF. August 2011.

Alvarez, Robert. “Uranium Mining and the US Nuclear Weapons Program.” Federation of American Scientists. 14 November 2013.

Edmonson, Catie. “Senate G.O.P. Includes Expanded Fund for Radiation Victims in Policy Bill.” New York Times. 12 June 2025.

Hawley, Josh. “Op-Ed: Don’t Cut Medicaid.” New York Times. 12 May 2025.

Kite, Allison. “Records reveal 75 years of government downplaying, ignoring risks of St. Louis radioactive waste.” Missouri Independent. 12 July 2023.

Benen, Steve. “Senate Republicans’ megabill is even more brutal than the House’s version, CBO says.” MaddowBlog, MSNBC. 30 June 2025.

Senator Josh Hawley. “Hawley Secures Historic RECA Expansion in Base Text of ‘Big, Beautiful Bill’.” 12 June 2025.

Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium. Email blast. 30 June 2025.

This figure is accurate as of 30 July 2025.

Wheeler, Joshua. Acid West (pg. 39). New York: MCD x FSG Originals. 2018.

“New Mexicans claim cancer is living legacy of world’s first atomic bomb test.” PBS NewsHour. 28 July 2015.

“Hanford Overview.” Department of Ecology. State of Washington.

Frank, Joshua. Atomic Days: The Untold Story of the Most Toxic Place in America. Haymarket. 2022.

As mentioned in an earlier iteration of Time Zero, an even higher figure—250,000 deaths, over time—is what I believe to be a relatively conservative estimate, based on a reasonable and diligent interpretation of a wide variety of sources, including: The International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons. “Hiroshima and Nagasaki Bombings.”; Wellerstein, Alex. “Counting the dead at Hiroshima and Nagasaki.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 4 August 2020.; National Archives. “The Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.”; and multiple other sources.

National Parks Service. “Manhattan Project National Historical Park: Frequently Asked Questions.” Accessed 17 November 2024.

Oak Ridge Associated Universities. “Trinitite.” Museum of Radiation and Radioactivity.

Blume, Lesley M. “Collateral damage: American civilian survivors of the 1945 Trinity test.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 17 July 2023.

Gilbert, Samuel. “The Forgotten Victims of the First Atomic Bomb Blast.” Vice. 24 July 2016.

Tucker, Kathleen M. and Robert Alvarez. “Trinity: ‘The most significant hazard of the entire Manhattan Project.’” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 15 July 2019.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Monasterky, Richard. “First atomic blast proposed as start of Anthropocene.” Nature, 16 January 2015.

Morton, Timothy. Dark Ecology (pg. 09). New York: Columbia University Press, 2018.

“New Mexico Downwinders Push for National Recognition.” YouTube, uploaded by New Mexico in Focus. 28 July 2023.

New Mexico Farm & Ranch Heritage Museum. "McDonald, David G". Archived from the original on October 19, 2014. Accessed 16 November 2024.

White Sands Missile Range Museum. “Trinity Site: The Schmidt/McDonald Ranch House.”

Rhodes, Richard. The Making of the Atomic Bomb (pgs. 1097-1098). New York: Simon & Schuster. 1986.

Democracy Now! “Scientists Examine Biological Damage From Depleted Uranium.” 21 December 1998.

Voices of the Manhattan Project. “Emilio Segrè’s Interview.” 29 June 1983.

“Countdown.” Los Alamos: Beginning of an Era, 1943-1945. Los Alamos: Bathtub Row Press.

Szasz, Ferenc Morton. The Day the Sun Rose Twice: The Story of the Trinity Site Nuclear Explosion, July 16, 1945 (pg. 142). Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1984.

Office of Scientific and Technical Information. “Potsdam and the Final Decision to Use the Bomb.” The Manhattan Project: An Interactive History.

“Harry S Truman: Special Message to the Congress on Winning the War With Japan. 01 June 1945.” The American Presidency Project. University of California Santa Barbara.

Fox, Sarah Alisabeth. Downwind: A People’s History of the Nuclear West (pg. 51). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. 2014.

Wheeler, Joshua. Acid West (pgs. 84-85). New York: MCD x FSG Originals. 2018.

Oppenheimer. Directed by Christopher Nolan. Universal Pictures. 2023. 01:45:56.

Ibid. 01:48:46.

“Cillian Murphy, Emily Blunt & Robert Downey Jr on Making Oppenheimer, Oscar Nominations & Matt Damon.” YouTube, uploaded by Jimmy Kimmel Live! 23 February 2024. 07:43.

“Oppenheimer Writer And Director Christopher Nolan On The Terrible Beauty Of An Atomic Explosion.” YouTube, uploaded by The Late Show with Stephen Colbert. 8 February 2024. 03:40.

Atomic Heritage Foundation. “Trinity Eye Witnesses.” National Museum of Nuclear Science & History.

Nuclear Watch New Mexico. “Kirtland Air Force Base Nuclear Weapons Complex.”

Blume, Lesley M. “Trinity Nuclear Test’s Fallout Reached 46 States, Canada and Mexico, Study Finds.” New York Times. 20 July 2023.