03: A Low-Use Segment of the Population

Look what we'll do to our own land and people. Imagine what we'll do to yours.

03: A Low-Use Segment of the Population

NOTE: you can listen to this episode using the player linked above, or for free on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

You can also access full essay versions of each installment at timezeropod.com.

Subscribe (or upgrade to a paid subscription).

In early August 2024, I was on a video call with Joy Lehuanani Enomoto, a visual artist, activist, and director of Hawai’i Peace and Justice. After brief introductions, Joy dived right in.

“I’m not sure if we want to go into what happened in the Marshalls?”

“We do,” I replied.

“So, following World War II, 67 nuclear tests were carried out in the Marshall Islands.”

Between 1946 and 1958, the United States staged 67 nuclear detonations at what the military called the Pacific Proving Grounds in the Marshall Islands, a former territory of Japan seized by the US after the war. The Marshalls are located about halfway between Hawai’i, where Joy lives, and Australia.

Part of the broader Micronesia region, the Marshalls have been home to Indigenous inhabitants for thousands of years and include five major land masses, a thousand smaller islands, and dozens of atolls, which are ring-shaped, coral-rimmed islands that encircle a central lagoon.

During the Pacific weapons program, the US exploded 44 nuclear weapons at the Enewetak Atoll, and another 23 at Bikini Atoll (after which, cruelly, the swimsuit got its name1).

“They literally removed people from Bikini Atoll,” Joy said.

At the time, the population of the Marshall Islands was close to 30,000. There were over 90,000 people in total living across the Micronesia subregion of Oceania2.

“And Henry Kissinger said something like, ‘93,000 people. Who cares, right?’ They moved them, saying that they were doing this great thing for humanity, in this nuclear testing. The impact was so severe that… there's a there's a famous thing called Project 4.1. They were actually using the Marshallese people as guinea pigs to see the fallout effects of nuclear testing.”

Project 4.1, formally titled “The Study of Response of Human Beings Exposed to Significant Beta and Gamma Radiation Due to Fallout from High Yield Weapons”3, was an experimental, nonconsensual medical study that the United States conducted on Marshallese people after the Castle Bravo detonation at Bikini Atoll in March 1954 4.

Nine years earlier, in August 1945, the US dropped nuclear bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, instantly killing at least 150,000. The toll soon exceeded 250,000, as fires spread and radiation sickness took hold, with countless more deaths in the following years5.

The bombings ended World War II but sparked the Cold War between the US and the USSR, which had fought together in Europe as allies. Despite American mythologies, many historians argue that it was the Soviets, not the United States, who defeated the Nazis.

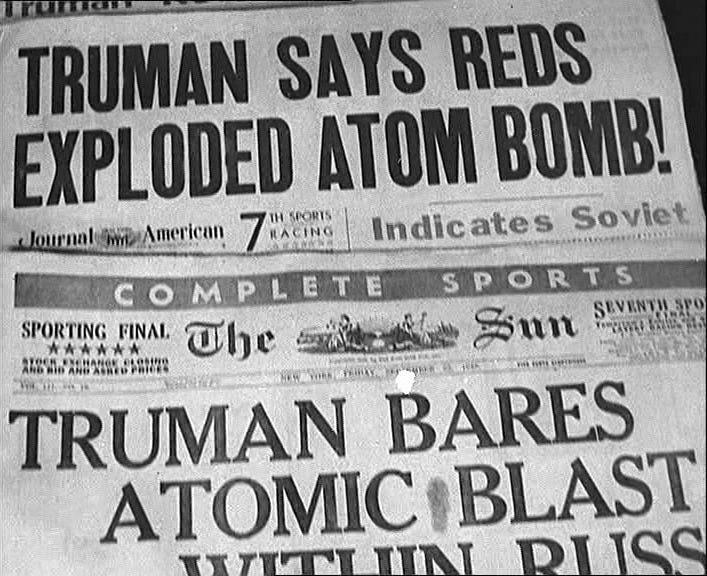

After the war, ideological tensions between Soviet communism and US capitalism deepened, shaping American life for decades. But another, more existential rift came from the US having secretly developed the bomb, excluding the Soviets. Some Manhattan Project scientists, including Oppenheimer, urged transparency to prevent an arms race. Military leaders refused. But Soviet spy Klaus Fuchs, a Los Alamos employee, had already given Stalin nuclear designs6. Even so, the USSR didn’t detonate its first bomb until August 1949, in Semipalatinsk, Kazakhstan.

Weeks after the first nuclear weapons detonation, a news reel titled “Russian Atom Blast Shakes UN Assembly” circulated, showing reporters rushing to Flushing Meadow as Russian Foreign Minister Andrey Vyshinsky arrives to address the United Nations. The narrator says:

The Russian Foreign Minister maintains his silence about Russia's atomic progress in his address. He accuses the West of planning atomic war and urges the outlawing of atomic weapons but he makes no reference to Russian agreement on international inspection, keystone to control.

US Secretary of State Dean Acheson appears, saying:

“In connection with the President's statement that there has been an atomic explosion in the Soviet Union, I wish to emphasize that from the very beginning of the development of atomic energy this nation has been determined to do everything in its power to proceed toward a truly effective international system of control”7.

The United States, however, hadn’t waited for the Soviets to demonstrate nuclear capacity before escalating, despite Acheson’s nods to international control.

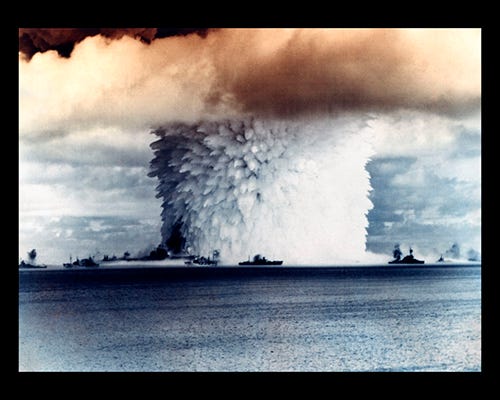

By the time the USSR detonated its first atomic bomb, the US had already detonated multiple nuclear weapons in the Marshall Islands. It began in 1946 with Operation Crossroads, during which the military displaced the residents of Bikini Atoll so they could nuke it.

For Crossroads, nearly 100 target vessels—battleships, aircraft carriers, submarines—were parked in the Bikini lagoon, stocked with live pigs, goats, rats, and guinea pigs to measure radiation exposure.

The first delivery, Able, was a plane-dropped bomb that missed its target. To the press corps’ disappointment, it sank only five ships.

The second bomb, Baker, an underwater blast, unleashed radioactive seaspray and fallout. It sank multiple ships, while those that remained were too contaminated to salvage—so the military simply sunk them. Atomic Energy Commission chairman Glenn Seaborg called it “the world’s first nuclear disaster”8.

Survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, or the Trinity Downwinders, might have taken issue with Seaborg’s qualifier “first.”

As Russia continued to expand its nuclear weapons program, the United States ramped up activity in the Pacific, eventually pursuing physicist Edward Teller’s hydrogen bomb, a weapon whose scale is categorically horrific.

On November 1, 1952, the U.S. detonated Ivy Mike, the first full-scale thermonuclear bomb. Weighing 74 metric tons, Mike was not a deployable weapon, but rather a literal building. Its 10.4-megaton blast—that’s 10.4 million tons of TNT—vaporized an island, left a mile-wide crater, and spread massive radioactive fallout.

Edward Teller, 5,000 miles away in Berkeley, didn’t need a phone call. His seismometer picked up the explosion before the military could report it9. Teller immediately sent an unclassified telegram to a physicist at Los Alamos that read:

It’s a boy10.

“Let's detonate a bomb underwater and see what happens,” said photographer Michael Light, over a video call in July 2024. “Well, you know, they sink. Big surprise.”

Michael, who is based in the San Francisco Bay Area, is also a pilot and a diver, two skill sets that have resulted in some pretty unconventional photography projects.

“And so, at the bottom of Bikini Lagoon, at 180 feet of water, are all these ships moldering away like Alka-Seltzer in a glass… fully fueled and fully armed.”

In 2003, Light dived those 180 feet to the bottom of Bikini Lagoon and photographed the dissolving warships that had been sunk during the Crossroads series.

This incredibly demanding and dangerous school of SCUBA diving is called “wreck diving.” Spoken out loud, it sounds like recreational diving. But it’s much more intense: it’s hunting for sunken ships.

“Wreck diving is like cave diving, and is a very particular branch of scuba diving that is generally populated by really intense Navy SEAL-type dudes who have a ‘lust for rust.’”

Breathing compressed air at 180 feet of depth causes nitrogen narcosis. Michael describes feeling high as a kite down there. At that depth, you’re also going into compression diving.

“If you spend 20 minutes at a depth, you actually have to spend like an hour-and-a-half slowly going up and letting the nitrogen escape from your bloodstream or else it's like popping the cap on a Coke bottle and, you know, like… fizz.”

The same year that Light dived into Bikini lagoon, he released the book 100 Suns, an alarming collection of one hundred images that the artist culled from the National Archives and Los Alamos documenting atmospheric nuclear detonations by the United States.

As a sort of haunting complement, in 2006, he put out a large-format book of his underwater and aerial photos from Bikini Atoll. A year later, he returned to the Marshall Islands, this time shooting digital images of those dissolving Crossroads vessels.

The Crossroads series, however, paled in comparison to the Castle Bravo detonation at Bikini Atoll in 1954.

“And this was a hydrogen bomb that was also Edward Teller’s doing. And they were playing with isotopes of helium, which you could, sort of, dial up or dial down. This one turned out to be three-and-a-half times larger than expected, for a total megatonnage of 15 megatons—which is, indeed, a thousand times greater than the bomb we dropped on Hiroshima

How is one supposed to even consider violence at that volume?

“Unfortunately, the disaster part—aside from just the scale of this thing—the winds blew back over Bikini Atoll, irradiating service people, irradiating the entire north of the Marshall Islands, severely impacting all the native inhabitants, the Marshallese in all the northern atolls.

Bikini had been evacuated in 1946, and hasn't been really settled since. But now it's actually uninhabitable. You can be in Bikini, but you can't drink the water. You can't eat anything that's grown there. You cannot eat the coconut crabs. You can't tell a child not to eat a coconut, or coconut crabs.

The Bikinians can’t go back to their homeland. It’s creepy. And it’s heavy. And it’s sad. You’ve got four particular colonial empires, starting with the Spanish, then the Germans, then the Japanese, and now the Americans in the Marshalls. It’s a heavy place. And the Marshallese, consistently, have gotten the wrong end of the stick—through no fault of their own.

They have lived in the Marshalls for 3,000 years.”

If you’re wondering what the United States did, in terms of environmental remediation in the ensuing years, here again is Hawai’i-based artist and activist Joy Lehuanani Enomoto.

“What happened after years of the Marshallese people, and people in the Pacific, demanding that these tests end? There was a cleanup, right?

So, the tests were ‘successful’ and there was a cleanup that involved young Army personnel who went to this island called Enewetak.

Enewetak was hit by an explosion that broke the island and created a crater so big that they were able to take nuclear waste and pack it into this. And cap it. The capping is just a cement dome.

The explosion that produced that crater at Enewetak was the Cactus blast in 1958, part of the Hardtack series. And the cap Joy mentioned is the Runit Dome, a 400-foot-diameter, 18-inch-thick concrete dome meant to contain radioactive debris from US nuclear weapons, that is cracking and leaking. The surrounding area is now more contaminated than the dome itself11, which contains plutonium-239, a cancer-causing element with a half-life of 24,000 years.

Military veterans and contractors who worked on the cleanup effort were given no protective gear and, following orders, also dumped significant amounts of waste directly into the lagoon12.

“Nearly every one of those men who loaded that waste died of cancer… and the Army, they're not taking any responsibility for how they died or why they died.”

Meanwhile, in addition to their own elevated rates of cancer, the Marshallese were facing what can only be described as abject horrors.

“Women were producing things that we called jelly babies, with no spines. They're unrecognizable. And this continued for years.

The US said to the Marshallese people, you can come to the US, and you will have health care in perpetuity for these crimes against humanity that they committed.”

On October 21, 1986, the United States officially recognized the independence of the Republic of the Marshall Islands through the Compact of Free Association. The US promised to provide economic, technical, and healthcare assistance to the Marshallese, as well as US military defense support. It also allowed the Marshallese unrestricted travel to and from the US.

In exchange, the Marshallese had to give the US total and exclusive access to their airspace, land, and waterways for strategic purposes13.

Naturally, many Marshallese traveled to Hawai’i for medical care. It’s 2,000 miles closer than California. But medical care in Hawai’i was already, Joy says, underfunded, which created obvious tensions.

And so, of course, then the Marshall Islanders are then pitted as a welfare burden. They're a burden to us, on our health care system.—they're getting something for free. And literally their whole island system was devastated by the United States.

In 1996, President Bill Clinton’s welfare reform bill cut the Marshallese off from federal aid, including Medicaid14. They remained excluded from U.S. healthcare for nearly 25 years until the Covid-19 pandemic forced change15.

The Nuclear Claims Tribunal, established in 1988, provided limited compensation to some Marshallese downwinders16—but only those from select islands, despite widespread fallout from detonations like Baker, Ivy Mike, and Castle Bravo. That fund was depleted in 200917.

Now, the Marshallese face another crisis: rising seas fueled by climate change. Yet, like many Indigenous peoples, they refuse to abandon their home, which they have occupied for millennia.

And their story is gaining attention.

Marshallese poet and activist Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner gained international recognition at the 2014 UN Climate Summit and has been featured on CNN and NBC News, and in National Geographic and Vogue.

In 2020, Vice produced a documentary on the Runit Dome, which has been viewed millions of times.

Meanwhile, surviving veterans of that disastrous nuclear cleanup on Enewetak continue to share their stories.

And photographer Michael Light found himself back in the Marshall Islands in August 2023, as part of a 12-day expedition called Our Life is Here. Led by Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner and British artist David Buckland, the project involved a team of 30 international, Oceanian, and Marshallese artists, writers, scientists, and filmmakers, who traveled 450 nautical miles together.

Along the way, they were introduced to island cultural knowledge, learned traditional maritime navigational skills, and spent time honoring the atolls irradiated by US nuclear weapons. Importantly, the expedition brought along six Marshallese youth artists, many of whom were making their first journeys to significant ancestral sites.

As the Our Life is Here expedition prepared to set sail in the Pacific, I was in El Paso, Texas. It had been two weeks since I attended the Trinity Downwinders’ luminaria vigil in Las Cruces, and just one week since Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer proved summer blockbusters were still possible post-pandemic.

It was at the El Paso Museum of Art that I was introduced to the work of Joy Lehuanani Enomoto and Kathy Jetn̄il-Kijiner.

Exposure: Native Art and Political Ecology was a groundbreaking traveling exhibition that had started at the Institute of American Indian Arts Museum of Contemporary Native Arts in Santa Fe in 2021. Exposure gathered Indigenous artists’ responses to atomic weapons industries, nuclear accidents, and uranium mining. Representing artists from Australia, Canada, Greenland, Japan, the Pacific Islands, and the US, it was the first show of its kind.

Joy’s piece, Nuclear Hemorrhage (2017), directly confronted U.S. nuclear legacies in the Marshall Islands. She described its technical and thematic elements to me during our video call last summer.

“Nuclear Hemorrhage is actually a combination of watercolor and stitching on paper.It's a red coral fan that leads into the Enewetak cap placed by the army to hide all of the nuclear waste. At the bottom is a Nautilus shell.

And everything in that fan is stitched—I really like stitching directly into paper. The colors go from sort of nuclear colors—yellow and orange and red—into the blues, leaching. That cap is starting to leak into the blue of the ocean.”

The nautilus shell has been on earth for almost 500 million years18, and is, Joy says, one of the oldest Oceanic cultural symbols. Coral is also important.

“In our origin story, coral is one of the first things ever created, out of the depths of the sea. We actually come from the bottom of the sea, which we call Pō. So the the way that we're going to regenerate is coming out of the sea. The sea is our whole life. There is no there is no life without the sea. It begins in the ocean."

As Joy mentioned earlier, she directs Hawai’i Peace and Justice, a multigenerational, multi-ethnic group advocating for peace, social equity, and environmental justice in Hawaiʻi. In July 2024, she co-authored a sharp critique in the Sri Lankan Guardian of the US military’s biannual Rim of the Pacific exercises, which devastate Pacific ecologies with ship sinking, live weapons, and staged assaults19. This kind of environmental and cultural violence echoes the U.S. military’s midcentury nuclear assault on the Marshall Islands.

“The ocean is is being expected to absorb all of our sins, so to speak. And I think it will do that. But we will no longer be a part of it. Like, I think the ocean is going to do a lot of things. I'm not worried about the Earth at all. I'm worried about humans on the Earth, and animals on the Earth. For the Earth, we're just afterthought. It's got a way to actually, in its own time, absorb, deal with, produce new things.

Eventually, the U.S. government and military decided the Marshall Islands were too remote to serve as the primary nuclear detonations site. Transporting materials and personnel was expensive, and concerns grew over potential espionage.

Within a year of Russia’s first nuclear bomb, President Truman established the Nevada Proving Grounds, just 70 miles north of Las Vegas. The Western Shoshone maintain to this day that this land was taken in direct violation of the 1863 Treaty of Ruby Valley20.

Despite Indigenous opposition—and internal government concerns about detonating nukes on U.S. soil—the military moved forward. In 1951, they dropped their first bomb there: Able, the same name as the first Crossroads weapon in the Pacific.

At the same time, activity continued in the Marshall Islands until 1958, when U.S. nuclear detonations permanently shifted to the Nevada Test Site.

From 1951 to 1962, the U.S. set off 100 earth-shaking, above-ground nuclear blasts in Nevada. Most of these bombs were far more powerful than those dropped on Japan. On several occasions, American soldiers were stationed in close proximity to the blasts, to see how they’d handle—physically and psychologically—nuclear war21.

After the 1963 Limited Test Ban Treaty, blasts moved underground, with another 828 bombs detonated until George HW Bush ended live nuclear weapons demonstrations in 1992.

As early as 1957, groups were showing up at the southern entrance of the Nevada Test Site to protest nuclear weapons detonations.

Demonstrations at Peace Camp, as it came to be known, were loosely organized, but consistent, for the next thirty years.

The decade stretch between 1985 and 1994 is considered the “peak years” of Peace Camp, which saw more than 500 organized demonstrations by an estimated 37,000 people. Almost half of those people were arrested22. Diverse groups participated, including Western Shoshone, Southern Paiute, Quakers, Greenpeace, survivors from Hiroshima and Nagasaki, US veterans subjected to atomic explosions, and downwinders from the Four Corners region, the Marshall Islands, and Kazakhstan.

Protests continue to this day at Peace Camp, as the Nevada Test Site remains active—militarily, but also radioactively.

“I can't remember how I found Peace Camp, but it was basically a campground by the nuclear test site in Nevada. I'm Richard Misrach. I'm a photographic-based artist here in Berkeley, California. I grew up in LA and came to Berkeley in the ‘60s and started photographing the street protests of the Vietnam War. I’m 75 and still photographing and loving it.”

Getting to Zoom with Richard Misrach was a little surreal. You learn about him in art school, early on, as one of the great contemporary American landscape photographers.

Richard is also mentioned several times in Rebecca Solnit’s 1994 book Savage Dreams, which looks at what Solnit calls the “landscape wars” of the American West. Solnit’s brother, the artist and activist David Solnit, was an active participant at Peace Camp in the 1980s and 90s, and Richard frequently showed up, both to document and to protest.

“These were people just camping and doing normal protests. And then there was a group there of women, the Princesses Against Plutonium.

They wore radiation suits and death masks and then would go and hike in and protest and get arrested. And other people got arrested. I actually got arrested and became friends with the Princesses. I loved them. They were amazing women. And I became an honorary Princess. And I got a radiation suit and death maks and I got arrested in that.

I also participated here at my studio, where I'm sitting right now. I had a landline back then—we didn't have cell phones—and on my landline I left a message. Something to this effect—it's been 40 years, so forgive me:

‘You’ve reached the Northern California Headquarters for Nuclear Disarmament. The next organization will be, you know, on May 3rd, protesting, etc.’

It it was just me, the Northern California Headquarters for Nuclear Disarmament, but it made it sound like I'm a giant groundswell of activists. And people would end up showing up there. It worked!

I was I both was bearing witness with the camera—photographing documents of that historical moment which seems to have been erased by all government officials—but I also was, in my own way, participating in the actual protest.”

Another American photographer who has produced some of the most resonant images of the nuclearized West is Emmet Gowin.

Gowin is the only photographer ever permitted to make aerial images of the Nevada Test Site, which he shot from an airplane during three visits from 1996 to 1997. The scale of the devastation on the landscape is horrific, the surface so pockmarked by craters that it looks like an alien planet.

In 2019, Pace Gallery in New York staged an exhibition of this work, The Nevada Test Site, and Princeton University Press published an accompanying book. The book is a haunting object, absolutely worth purchasing. But if you’re not in a position to drop $55, you can see several of the photographs, and read an impactful text by Southwest writer Terry Tempest Williams, a downwinder who lost many family members to cancer, in a 2022 High Country News article.

“Nuclear weapons,” Terry Tempest Williams writes, “are not a safeguard against war, they are the harbingers of a violence ready made and waiting. It is human nature to use the tools we have made, no matter how vile”23.

In total, 928 atomic bombs were exploded in Nevada. That’s a nuclear explosion every two weeks, for forty years, one hour north of Las Vegas.

As I said before, Nevada is the most nuked place on Planet Earth.

Exploding 928 nuclear bombs wasn’t about research. It was about sending a message to the Soviets:

Look what we’ll do to our own land and people. Imagine what we’ll do to yours.

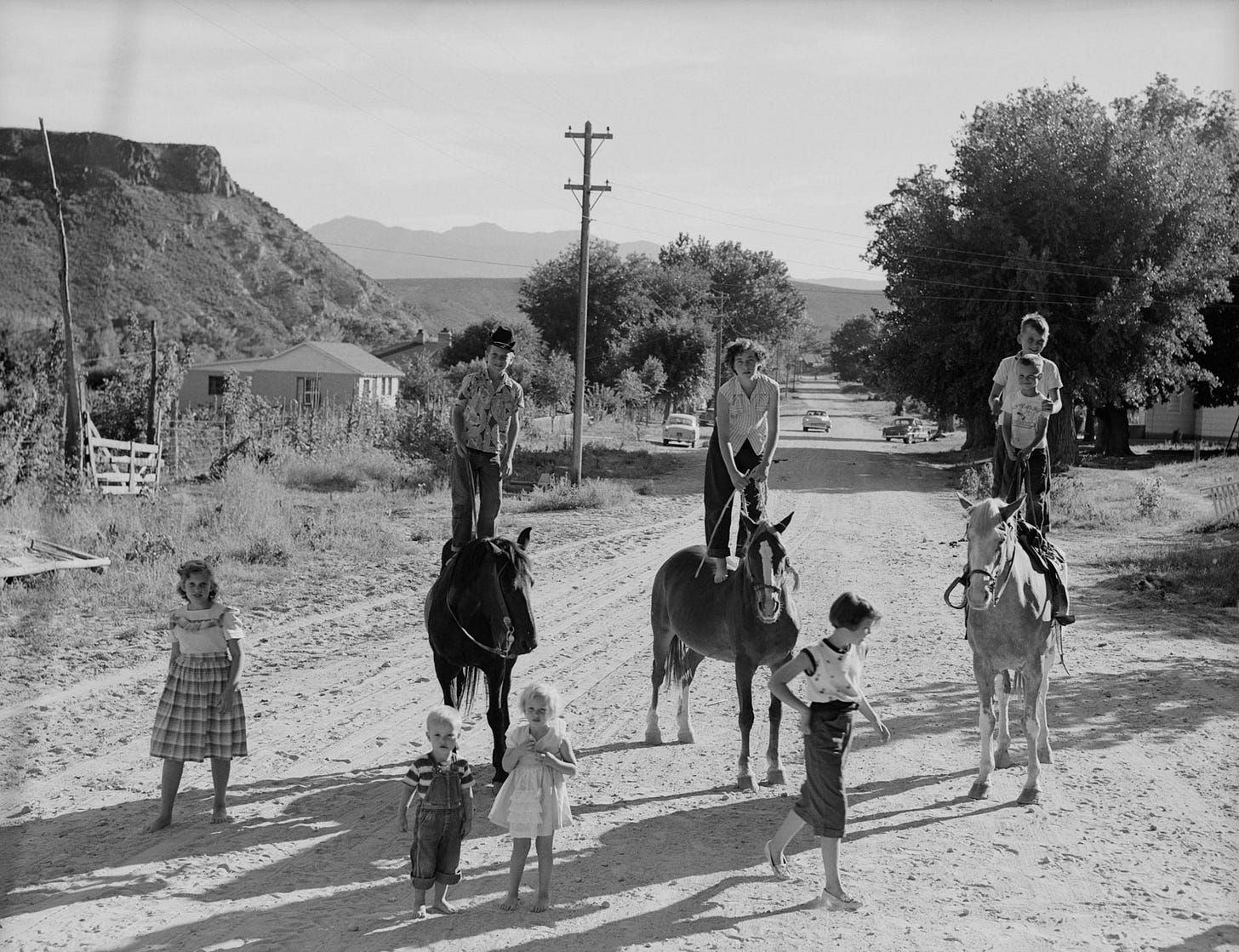

Wholly aware that radioactive fallout was deadly, the government only set off the bombs if the winds were blowing to the north or to the east. This would avoid sending fallout over larger population areas like Las Vegas, Phoenix, Los Angeles, or San Diego.

As for the smaller, rural pockets of people living all over to the north and to the east?

In classified memos, the Atomic Energy Commission dismissed them as a “low-use segment of the population”24.

“Very central to that history of nuclear weapons and nuclear weapons testing is the imagination of wastelands or uninhabited spaces,” said American geographer and artist Trevor Paglen, during our June 2024 video call.

Known for documenting hidden surveillance infrastructures and military black sites, Paglen has investigated places like Area 51 and Dugway Proving Ground (where the U.S. has tested napalm, anthrax, Botulinum toxin, and bubonic plague).

Paglen developed what he calls limit telephotography, repurposing deep-space camera equipment to capture distant terrestrial sites. Often, this means climbing mountains dozens of miles away to get the right vantage point. His images are hazy, abstract. Unlike photographing Jupiter—where, after a few miles of atmosphere, space is clear—shooting across desert landscapes means battling heat waves, dust, and distortion. Yet from these seemingly empty spaces, Paglen’s creative misuse of photographic technologies reveals parked bombers, secret prisons, and classified military architecture.

“And so the idea is that you create this imaginal space where nothing exists, and that becomes an alibi for doing whatever you want there. For example: blowing up thousands of nuclear bombs. And, of course, they're not uninhabited spaces. They're just inhabited by people, in the case of the Nevada Test Site, called Western Shoshone.”

Photographic technologies and materials actually play significant roles in nuclear histories. The desire to document atmospheric nuclear blasts in millisecond frames led to the development of advanced camera capabilities—and those archives of nuclear explosion images that Michael Light dug through for his book 100 Suns.

In a bizarre bit of Manhattan Project trivia, radioactive fallout from the 1945 Trinity detonation traveled far enough to contaminate packaging being produced for Kodak x-ray film at plants in Iowa and Indiana, fogging the film that went out to customers25.

After detonations started at the Nevada Test Site, the Rochester-based Kodak threatened to sue for damages. But the Atomic Energy Commission brokered a deal26. The AEC would give Kodak a heads up before each bomb, so they could take precautions to protect their product. In return, Kodak, as patriots, would keep quiet27.

The Nevada Test Site created major environmental and health problems for both the Western Shoshone and the Southern Paiute peoples, whose history in the Great Basin predates the arrival of Europeans by, at the very least, multiple centuries.

In 2022, PBS aired the documentary Downwinders and the Radioactive West. Appearing in the film was former Utah Democratic Congressional Representative Jim Matheson, who points out:

“There were Native American populations within the range of fallout that were clearly ignored, just like all other downwinders. I don't think any consideration was given to protect folks from those risks on those reservations. And it's just another chapter in this story of where the government put people's lives at risk in the name of developing nuclear weapons”28.

Matheson’s father, Scott Matheson, who served as governor of Utah from 1977 to 1985, died at age 61 of multiple myeloma, a rare cancer the Matheson family attributes to radioactive fallout from the Nevada Test Site.

Also in the documentary was Ian Zabarte, Principal Man of the Western Shoshone.

“Testing at the Nevada test site historically has been conducted in secret,” says Zabarte. “It is a violation of the treaty of Ruby Valley. We began experiencing adverse health consequences, known to be plausible from exposure to radiation, soon after the weapons testing began”29.

In a video uploaded to YouTube by user S Bell in April 2019 titled “Nuclear Fallout Impacts to the Western Shoshone Nation,” Zabarte describes health consequences his family has experienced living downwind from the Nevada Test Site.

“My uncle died of cancer of the esophagus. My grandfather died of an autoimmune disease, which ravaged his whole body, and he got a heart attack. His whole body, his skin, became hard, and peeled off. So, these are the kinds of strange things—he died of a heart attack—but these are the types of exposures, or health abnormalities, that result from exposure to radiation”30.

Make no mistake: the government knew nuclear fallout caused cancer3132.

But when it came to the Western Shoshone, Southern Paiute, or rural Utahns and Nevadans, the government simply didn’t care.

When I arrived in St. George, Utah, on June 13, 2024, I was immediately struck by the incredible red mesas rising up around the quaint, but quickly growing, town of just over 100,000 people. But the trails would have to wait; I had an interview scheduled at 1:00 p.m., so I headed straight to the Intermountain Cancer Center at St. George Regional Hospital.

“My name is Rebecca Barlow. B-A-R-L-O-W. I’m the Project Manager for the Radiation Exposure Screening and Education Program in St. George, Utah… I grew up in Salt Lake City. But I moved down here in 1987, so red dirt looks better than black dirt now.

When Congress passed the 2000 amendments to RECA…

A note about RECA and Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill…

As I mentioned in last week’s installment of Time Zero, after most of the show had already been recorded, an expansion of the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA) was quietly folded into Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill.

Established in 1990, RECA originally provided one-time payments to certain populations who developed specific forms of cancer after living downwind of the Nevada Test Site, working at a US nuclear site, or working in the uranium industry as a miner, miller, or transporter—though only up through 1971. In 2000, a slight expansion was added, which Rebecca discusses below.

When Rebecca and I met last summer, the June 2024 deadline for Congress to extend and expand RECA before it expired had just passed. That meant that people exposed in the Tularosa Basin by the Trinity detonation, downwinders in many places, post-1971 mine workers, and others would remain uncompensated and unacknowledged.

A few weeks back, RECA was added into the One Big Beautiful Bill to get Missouri Republican Senator Josh Hawley, whose state has multiple nuclear-contaminated sites33, to agree to $1 trillion in Medicaid cuts3435.

On July 4th, Trump signed it into law.

The bill extends RECA claims for two years, raises some compensation to $100,000, and covers uranium workers up until 1990, plus downwinders in parts of Idaho, Missouri, and New Mexico (including the Trinity Downwinders). It continues to exclude people in Montana, Colorado, and Guam.

This represents a bittersweet win: recognition tethered to a violent package that slashes Medicaid, basically triples ICE’s budget, and funnels nearly $200 billion in taxpayer funds to Lockheed Martin to build the so-called “Golden Dome,” a nuclear defense fantasy the CBO says will cost close to $1 trillion36—the exact amount cut from healthcare.

This is what I mean when I say that every major US policy decision is shaped by nuclear weapons.

Please keep this legislative change in mind as you read the rest of this text, though, as was the case with RECA’s previous incarnations, this still leaves thousands of people unrecognized and uncompensated.

“When Congress passed the 2000 amendments to RECA, that added a few more areas, a few more cancers. But it also allowed for grant a grants to be set up to form clinics, to help the people who were exposed, to get into the program.”

St. George is located just 140 miles east of the Nevada Test Site and, along with surrounding towns like Cedar City, experienced some of the most concentrated radioactive fallout in the world.

For twenty years, Rebecca has provided care and guidance to cancer victims from what the AEC called a “low-use segment of the population.”

“We see mostly downwinders, but also uranium workers, to help them understand their risk of cancer because of the radiation, and also to help them with the RECA claim process. So, we do both.

We do cancer screening physicals on them. We give them education on what the risk is from the radiation that they were exposed to. And then we also help them, if they're diagnosed with one of the qualifying cancers, to get the application process and go through it.”

The Radiation Exposure Screening and Education Program (RESEP) has multiple clinics.

“There are eight RESEP clinics right now throughout the areas of of New Mexico, through the [Navajo] reservation, Four Corners, us, Las Vegas, Flagstaff, and Denver, Colorado, has one. And each of us have a different clientele that we work with. Mostly, I'm like 96% downwinders. And I think that Denver is 98% uranium workers. So, we see different people, but we both help with the same idea that these people were exposed to the radiation, either from working in it or living downwind of the atmospheric detonations, and now are experiencing health issues because of it.”

St. George’s hospital is a major hub for regional downwinders. Besides Las Vegas, it’s easily the largest city for hundreds of miles. And while getting $50,000 from RECA as a downwinder doesn’t even come close to covering the costs of cancer care in the United States, Rebecca recognizes what the program can do.

“If we can get them that money, it is so relieving to them to be able to have some money so that the people who help them, they don't feel so much a burden to them, because they have something to give them for the care they're getting. And the family, it’s not even that the family that wants money. It just takes a big burden off their shoulders.”

And like so many of the people that we’ve heard from, Rebecca stresses that so-called testing has left generational legacies.

“I tell I tell the downwinders, when I do my education, you do what you can. So, make sure you're getting your screenings done, make sure you're getting your colonoscopies, your mammograms, everything that you can get done. Don’t be crazy and hyper-focused on it. But do what you can. Because it just makes sense that if your father's DNA was changed, so that he's more sensitive to cancer, and your mother's DNA was changed, so she's more susceptible to cancer, your DNA had to be changed, and you are more sensitive to it.”

The United States stopped atmospheric detonations in 1962. But even though another 828 underground weapons were exploded at the Nevada Test site over the following thirty years, you only qualify for RECA if you were exposed earlier than 1962.

“So, people who come who don't qualify for the program, because it's after July of 1962, I tell them, ‘You are a downwinder’s child. Do your screenings, watch what you can, get your skin checked. Catch it as early as you can, when it's easier to treat.”

RESEP, though heavy, is downright wholesome when compared to other nuclear-related health initiatives.

In 1958, the Greater St. Louis Citizens Committee for Nuclear Information collected 320,000 baby teeth to measure strontium-90, a key fallout component37. Their findings confirmed that atmospheric detonations had indeed spiked radioactivity in air, water, and milk. Children born in 1963 had 50 times more strontium-90 than those born in 195038.

Creepy, but it definitely helped convince Kennedy to halt above-ground explosions.

Less productive, and, arguably, even unholy: in the 1950s, the US secretly collected remains from 1,500 British and Australian cadavers—many of them children—without the consent of their families, for strontium-90 testing.

They called it Project Sunshine39.

The day after meeting Rebecca Barlow at the Intermountain Cancer Center, I visited the St. George Art Museum, an airy, mid-sized gallery downtown. There, I spoke with curatorial assistant Stephanie Wheeler, a lifelong Utahn.

“I don’t remember learning about the testing sites and Dugway and things like that in school as a kid, or even into high school. That’s really interesting to me. It’s the history of our area, but you’re only learning about certain histories, I guess.”

Stephanie grew up near Salt Lake City, nestled below the Wasatch Mountains and adjacent to the Utah Test and Training Range, a military bombing site, and Wendover Air Base, where the crews that nuked Japan trained. South of Salt Lake City is Dugway Proving Ground, the secret military site Trevor Paglen photographed.

For the last 15 years, Stephanie has lived in St. George, 140 miles east of the Nevada Test Site.

“I have always viewed St. George as a retirement community. I think that downwinders—that conversation—could very much be a part of the community, because so much of our community is in that demographic. But there’s almost this underlying feeling of, ‘We don’t want to talk about those things because we’re retired and we’re golfing.’

We’re not thinking about the serious implications of our location and the Nevada Test Site, and how those things still could be affecting us today. it’s interesting how they don’t have those conversations.

Melissa Carter, the the museum’s manager and curator, also joined the conversation.

“In Utah, uniquely,” said Melissa, “I think that people have an extremely selective memory.”

Melissa had been in Utah about six months, having recently relocated from California for the leadership role. Notably, Melissa is no stranger to the impact that environmental contamination has on people.

“I grew up in Lexington, Kentucky, not far from Eastern Kentucky. My ancestors have been in Eastern Kentucky for 150 years.”

We’d been talking about extractive industries in Appalachia.

“I have many relatives who have been coal miners, and then also that have made a lot of money in the coal mining industry, that are engineers. I think there—in Kentucky—it’s my perspective that people are much more political. Everyone knows about mountaintop removal and discusses it all the time and is really disgusted by it. All the mining, and everything that’s happened, all the cancers over the years. It’s not a thing that people can really ignore. They see it on the mountains every single day, and they live with it.

There’s music and quilt making about it. It’s woven in the fabric of what has happened there in Appalachia, forever. It’s much more a part of the politics of the area there. When you see babies being diagnosed with cancer, that stuff pervades. It gets in there. You can’t ignore the deaths and the suffering.”

I asked Melissa if she’d heard any parallel conversations here in Utah, about downwinders and their rates of exposure-related cancers.

“I see that less here, to be sure. This is a very apolitical area. And we can’t really speak critically about the government here.”

Stephanie nodded, adding, “St. George is a very conservative, predominantly Republican area.”

Earlier that spring, the St. George Art Museum hosted Crossroads: Change in Rural America, a traveling Smithsonian exhibition (not a reference to the nuclear detonations series in the Marshall Islands). The show featured regionally significant works, including a 1950s Life magazine series by Dorothea Lange and Ansel Adams, Three Mormon Towns, which documented daily life in Gunlock, Toquerville, and St. George.

Reportedly, creative differences between Lange and Adams caused a major rift. What lingers for me, though, isn’t their feud—it’s the eerie weight these photos carry now, knowing their subjects were unwittingly exposed to massive radioactive fallout from the Nevada Test Site.

Three Mormon Towns feels like a haunting prequel to Carole Gallagher’s American Ground Zero from 1993, which captured the devastation of regional radiation decades later. By the 1980s, when Gallagher was documenting downwinders in Southwestern Utah, the slow violence of atmospheric nuclear fallout had taken its toll.

I asked Stephanie and Melissa whether St. George might want to see an exhibition that centers downwinder stories. Stephanie offered her thoughts first.

“Ideally, I think it’d be really interesting to record voices, people sharing stories about being downwinders. But yeah, we do have to play the political game, as a municipally owned museum. We are run by the City of St. George, so, there definitely is politics in it.”

Stephanie’s referring to what would possibly be perceived as an embedded political agenda in hosting such an exhibition.

“We are trained and coached,” she elaborated, “to remain politically neutral.”

I asked why the city council or others might see a show where locals tell their own stories as explicitly political. I mean, it is political, in the sense that it relates to the government, who poisoned them, but it’s not “political” in the cultural way that Americans tend to use the word.

This isn’t hidden information. There are multiple documentaries on it. Even mainstream sources speculate that fallout from Nevada Test Site blasts caused cancers that afflicted nearly half the cast and crew of The Conqueror40—the widely panned 1956 film, shot in nearby Snow Canyon, where John Wayne played Genghis Khan in yellowface.

St. George had had these conversations before: in 1979, longtime Utah senator Orrin Hatch—a Republican and Mormon—held a town meeting where locals shared testimonies about their illnesses41. And with the 1990 Radiation Exposure Compensation Act, the government has, technically, already admitted fault.

Melissa responded, carefully.

“As Stephanie said, our museum is fully subsidized by the government. And I think facilitating any kind of critical discourse about anything that the government has done, ever, would be problematic, and it could be seen as overly critical. And, yeah, we must be apolitical here.”

Melissa and Stephanie keep a good—and likely necessary—sense of humor about running a small art museum in the middle of a culture war. They certainly humored me, letting me record an interview in the museum’s offices.

Later, at my motel, listening back to my recordings, I noticed something else. Rebecca Barlow, the nurse from the Intermountain Cancer Center, who has spent two decades caring for nuclear victims, also seemed to have absorbed that, in Utah, political neutrality is the path of least resistance.

“I am not going to have a political position. I don't want to do anything with the politics and get caught in the middle of that. But just to help people understand what their deadlines are and, you know, do what you can for them.”

I sympathize with Rebecca, and with Mellisa and Stephanie. I mean, for the last two years, I’ve been teaching art in Florida.

There seems to be a stark contrast between how downwinder communities in Utah, today, articulate their experiences versus those in the Marshall Islands or New Mexico. Race and privilege do play a role. Southwestern Utah is overwhelmingly white, while the Marshall Islands and southern New Mexico are not.

With whiteness often comes recognition. St. George downwinders qualify for the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act. Historically, Trinity downwinders and Marshallese have not. And Utahns seeking care for radiation-related cancers aren’t so quickly vilified as a welfare burden.

Whiteness is a sort of retroactive shield against some of the impacts of living downwind, but that alone doesn’t explain histories of silence in a community where exposed people continue to die.

Critically, the social structures of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints play a role. The U.S. government knew midcentury Mormons sought assimilation. And it exploited that fact.

“After being on the fringes of U.S. political culture for generations in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the LDS Church, by the time of the Cold War, is really pushing for mainstream acceptance and political power.”

I spoke with Sarah Fox in July 2024 over a video call. Several years ago, after having read Joshua Wheeler’s Acid West, I picked up Fox’s book Downwind: A People’s History of the Nuclear West.

“I would describe myself as, sometimes I say an environmental historian, but the term that I guess is closest to my heart is that I'm a folk historian. My scholarship is very much about investigating the way that people have told stories about places over time and, inadvertently, that interest led me into studying the history of nuclear weapons development in the Western United States.

I asked Sarah about the reluctance that Stephanie and Melissa had described in and around St. George, Utah. What was it about Mormonism that seemed to keep them quiet as they were being irradiated by nuclear bombs for four decades?

“You know, they've kind of pushed back a lot of practices—like polygamy—that were seen as an affront to the dominant culture. And they're really making a bid for political and economic power during the Cold War era. And so there’s a tremendous emphasis on patriotism. The LDS Church aligns itself really strongly with the federal government during much of the Cold War years. And culturally, there's this emphasis in the LDS Church on obedience and on particular kinds of hierarchy, church hierarchy, gendered hierarchy.”

There is also, though, Sarah emphasized, a remarkably strong care ethic in the LDS church. People show up for one another. The church tries to make sure everyone has what they need. It’s almost, in some ways, kind of socialist. But there’s a flip side.

“If you question authority, whether it's the authority of your husband, or the authority of your bishop, or the authority of the church, or the authority of the federal government—which, during the Cold War, the church was like, ‘The federal government is acting on behalf of God,’ essentially—you are excluded in really painful ways.”

This kind of blind deference proved… challenging, with nuclear explosions so visibly obvious.

A lot of women in southern Utah communities who could see the mushroom clouds—they could see the dust after the clouds, settling on their gardens and causing changes in the leaves—were hearing stories from their partners, who were ranching, about birth defects. They were helping out on those ranches and seeing these deformed animals being born. They were experiencing miscarriages. They were having children with birth defects.

There are parallels here, clearly, to what we know about birth defects in the Marshall Islands and in the Tularosa Basin following atmospheric nuclear detonations. These testimonies come from communities who were not in touch with one another at the time, in any way, shape, or form.

“So when they start asking, wait, is this really safe? The first person a lot of them asked was their bishop. They went to a person in the church leadership and, overwhelmingly, what these women relate is that they were told, ‘We don't get involved in politics. That's not for you to worry about. You need to trust the government.’”

Put it, as they say, on the shelf.

In late June 2024, I met up with multidisciplinary artist Cara Despain in Salt Lake City. Cara was born in Salt Lake City, and splits her time between there and Miami. The previous summer, in Las Cruces, I’d seen Cara’s massive solo exhibition Specter New Mexico at the New Mexico State University Art Museum.

One of the works, Test of Faith, which had shown previously in Miami and Orlando, was an interdisciplinary affair.

Visitors enter through a viridescent archway—reminiscent of both the Palace of Oz, and Stanley Kubrick’s obsessively symmetrical sets from 2001: A Space Odyssey—embedded with Depression-era uranium glassware glowing under UV lighting.

Inside, a three-channel video bathes the walls with declassified reels of atmospheric nuclear explosions at the Nevada Test Site. Despain mirrored the footage along its vertical center, resulting in these hypnotic but very demonic, Rorschach-like bursts. I found myself thinking about Isaac Asimov’s ultra-short story “Hell-fire,” wherein Satan’s visage emerges from a nuclear cloud.

Piped into the space through surround-sound speakers is a layered recording of “Love One Another,” a Latter-day Saint hymn, nodding to Despain’s familial ties to Cedar City, Utah.

“Cedar City is in southwestern Utah, not far from St. George, which is kind of the last town before you cross into Arizona or Nevada. It's right by Zion National Park. So it's kind of known for that geographic wowie rock formation stuff. It's also where my mom grew up. She actually grew up in a town west of there called Newcastle, but she spent her school-going days in Cedar, and went to high school and college there. And a big contingent of Utah downwinders were in Cedar City.

It’s like your quintessential rural, quaint Utah small city, small town—mostly sheep ranchers, Mormon settlers. That’s the demographic that historically has been there. But it's been growing a lot, so it looks and feels very different than when my mom was there.”

On the morning of May 19, 1953, Cara’s mom was eight years old and living outside Cedar City. At 05:00 a.m., the US military detonated a 32-kiloton hollow-core implosion device codenamed Upshot-Knothole Harry atop a 300-foot tower on Yucca Flat at the Nevada Test Site. Miscalculations and a sudden change in winds created an immediate state of chaos, as an even more enormous than usual radioactive cloud drifted towards St. George, Cedar City, and other southwestern Utah communities42.

Around 10:00 a.m., the military issued a somewhat less than urgent radio bulletin43.

“Ladies and gentlemen, we interrupt this program to bring you important news. Due to a change in wind direction, the residue from this morning’s atomic detonation is drifting in the direction of St. George. To prevent unnecessary exposure to radiation, it is better to take cover during this period. Parents need not be alarmed about children at school. No recesses outdoors will be permitted. There is no danger. This is simply routine safety procedure”44.

Fallout blanketed everything.

Cara talked about the broader impacts of fallout on Utah ranchers, as well as the aftermath of the Upshot-Knothole Harry blast.

“There are a lot of the Utah downwinders from that area. They were affected by the fallout and the radiation. Several of them, including one major family, the Bulloch family, who were sheepers, they were some of the first to raise alarm because they were seeing their sheep get beta burns. And they had sheep being born dead. The worst of it came after the Dirty Harry test.

That's the narrative floating around in that area, kind of like haunting that zone.”

Local ranchers eventually brought a lawsuit against the federal government, alleging that 4,000 sheep died as a result of atmospheric detonations in 1953 alone, spiraling the ranchers into insurmountable debt45. The federal government blamed poor ranch conditions.

In 1956 in Utah, Judge A Sherman Christensen, the first Mormon appointed to a US District judge position, ruled in favor of the federal government. In 1982, after seeing testing data that the sheep’s thyroids had 1,000 times the permitted radiation doses for humans, Judge Christiansen reversed his decision, citing government fraud46. But in January 1988, the Supreme Court struck down the reversal, denying the ranchers compensation.

When the “experts” at governmental institutions abandon the people they’re supposed to protect, communities turn to mutual-aid.

You’ll recall Tina Cordova and Mary Martinez White, and the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium, from our last installment. Nuked, and then ignored, by their own government, they started collecting and publishing their own regional health data. They’ve since documented five generations of illnesses in the wake of the 1945 Trinity detonation. They’ve also testified before Congress, and are the subject of Lois Lipman’s documentary First We Bombed New Mexico, currently making the festival rounds.

These types of community-organized hazard-detection and solution-seeking practices have a name: popular epidemiology.

Downwind author Sarah Fox described these methodologies, and their origins, in our July 2024 video call.

“Popular epidemiology really grows out of this kind of local knowledge, these local geography, local relationships, local people recognizing that something is going on that they can't quite quantify and they can't get people to take seriously.

So the term popular epidemiology, it comes from medical sociologist Phil Brown, who originally coined the term to describe what ordinary women were doing in Love Canal, New York, in the late seventies, to call attention to clusters of health problems in their kids and their families that were so densely concentrated, geographically, in this relatively small community, that these women knew something had to be going on.”

This resonated with me. As I mentioned in the first installment of Time Zero, my mom and her sisters grew up very close to the corporate-contaminated Love Canal, as well as several nuclear industrial facilities and dumps that surround Buffalo, New York.

“And I say women a lot because the work of popular epidemiology is often initially done by women in communities who aren't being taken seriously when they say there's some sort of health problem going on here.

And so Phil Brown came up with this term to describe this work that these women in Love Canal, New York, were doing, where they were building lists of all the kids who had particular health problems. They were drawing maps of neighborhoods and trying to account for particularly dense clusters of health problems. And they were using that data in an effort to get men in their community—scientists, journalists, political leaders, medical professionals—to take them seriously.

Because what often happens when women, who do a disproportionate amount of the caregiving labor in families and communities, identify health problems or bodily signs of disease ahead of some sort of formal diagnosis being made, they tend to be diagnosed as hysterical. This is a strategy that has been used to minimize women's ideas and politics for a really long time, this charge of excess emotionalism. And it was deployed very consistently in communities impacted by radiation exposure during World War II and the Cold War.”

A landmark case was brought in Utah in 1979 that included almost 1,200 downwind plaintiffs from Utah, Arizona, and Nevada: Allen vs the United States.

Judge Bruce S. Jenkins found in favor of the downwinders, holding the government liable for negligence. The federal government challenged the decision and, in 1987, the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals overturned Jenkins’s decision—not because they disagreed with his determination that the plaintiffs were irradiated, but because, they said, the government simply couldn’t be held liable for it47.

A few years later, partial justice was achieved with the establishment of the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act which—though broadly insufficient, financially speaking, and in terms of who it recognizes—did include the government admitting fault.

For decades, Mary Dickson was a news anchor at KUED-Channel 7 in Salt Lake City. And for just about as long, she’s been a downwinder activist.

“The way radiation exposure works, it’s cumulative. So, it wasn't like it just happened once. When you've got a 100 above ground test and 828 underground tests—many of which leaked massively—that means repeated and multiple exposures, which is far worse. And if you’re exposed in utero, your chances of developing cancer? Much higher. If you’re a young child? Chances are much higher. If you’re a girl, and a young child, you’re most at risk.”

Mary is a lifelong resident of Salt Lake City, Utah.

“I am what we call a downwinder. I'm a survivor of radiation exposure from fallout from nuclear weapons testing. I had thyroid cancer, so I survived that. And I have been a longtime advocate for survivors of nuclear weapons—not just in the US, but worldwide—and have spent most of my time doing that since I retired from public television.”

Mary still hosts a show on Utah PBS called Contact, and last summer, I used the show’s general contact form to see if somebody could put me in touch. One of the producers forwarded my request, and the next day, an email popped up on my phone, subject line:

It’s Mary Dickson.

I’d first heard Mary’s story in undergrad at Arizona State reading Carole Gallagher’s American Ground Zero, which put the faces and stories of the people living (and dying) downwind of the Nevada Test Site into the public consciousness. Mary and Carole met, coincidentally, when Mary was actually assigned to interview Carole.

She recounted this in a 2017 interview for the Downwinders of Utah Archive at the University of Utah.

“I was writing for an arts magazine called Neo, and they asked me to do a story on a woman who was doing an oral history on downwinders.

She was a photojournalist from New York who had come out to Utah to live and she was going around southern Utah, and then around the state. And then I remember her saying she went to Montana, and Wyoming. And I thought, ‘Well, why is she going there?’

And I had to interview her for an article. So, I’m interviewing her, and she’s talking about the diseases that are related—mostly the cancers that are related—to fallout, and when she said thyroid cancer, I just kind of nonchalantly said, ‘Oh, I had thyroid cancer.’

And she stopped, and that’s when she started interviewing me.

She’s like, ‘Where did you grow up? Did you drink milk?’ And, you know, asking me all these things.

’I grew up in Salt Lake,’ I said. ‘Yes, we drank milk, sometimes from my grandfather’s farm, from the cows.’

And that’s when she stopped and she said, ‘I want to interview you. You’re a downwinder.’

And I’m like, ‘Oh no, I’m not; I grew up in Salt Lake.’

And she goes, ‘Oh, you people are so naive.’

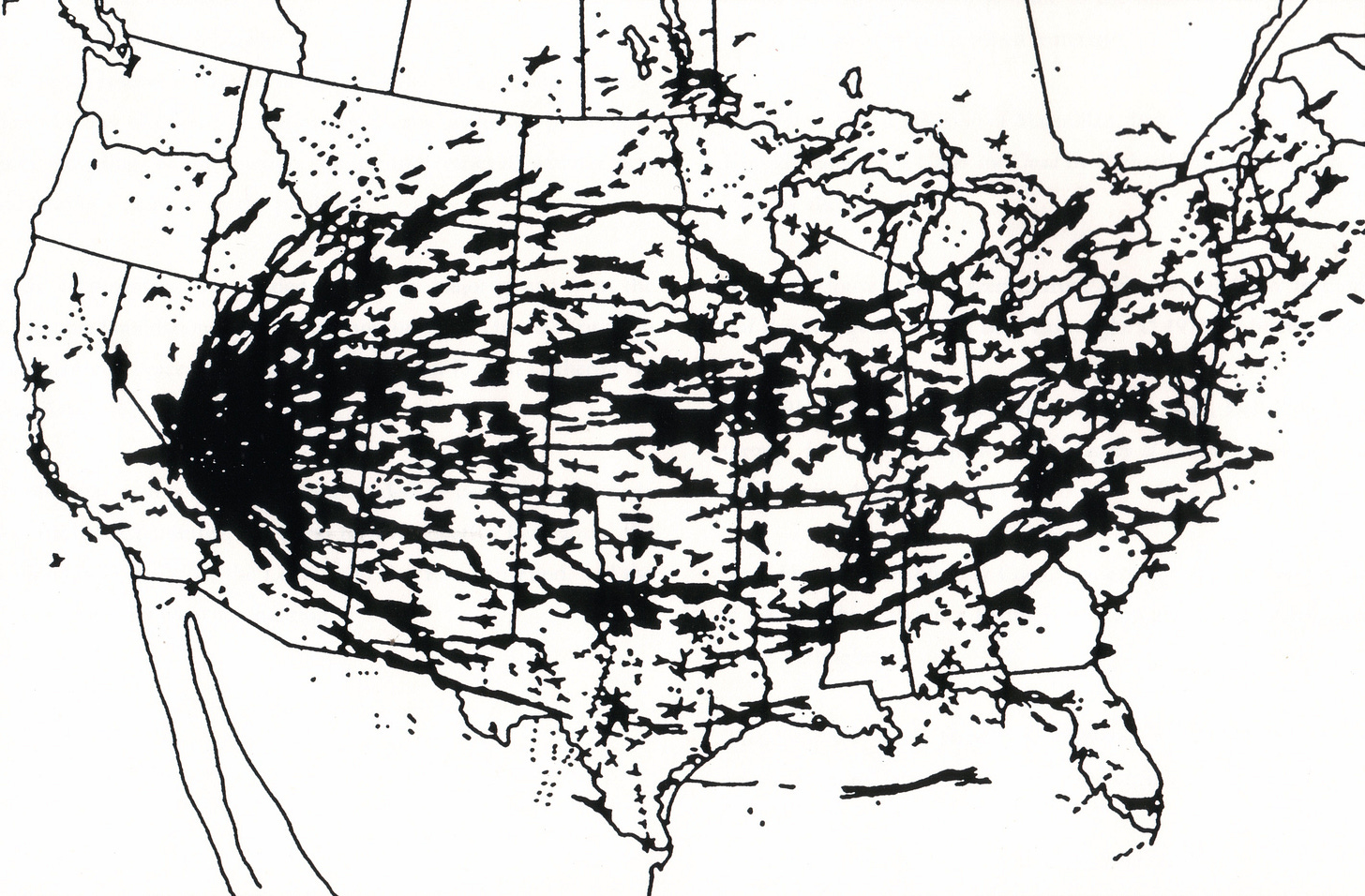

And she showed me Richard Miller’s map of where the fallout went”48.

The Miller map posits, as Mary Dickson often does: we are all downwinders.

Mary also appears several times in Sarah Fox’s Downwind, which had put her back on my radar, and reminded me of Carole Gallagher’s American Ground Zero.

When we spoke, Mary recounted to me the eerie innocence of her childhood.

“I grew up in Salt Lake City at the base of the [Wasatch] mountain range near a canyon. In fact, my neighborhood was called Canyon Rim. And I was a young child during the late fifties and early sixties, when nuclear testing was going on. But I wasn't really very aware of that. So I had this kind of idyllic childhood. We would go outside and we would play in the snow. We'd mix it with sugar and vanilla and eat it, pretending it was ice cream. When it rained, we'd go play in puddles of rain water. We drank fresh milk delivered from a local dairy to our doorstep every day. And we basically thought we had this wonderful childhood.

We had bomb drills in grade school, so the alarm would sound and we'd have to jump, grab a jug filled with water, and run to the basement. That was a bomb shelter in those days. And, you know, we did the duck and cover, where you jumped under your desk and put a newspaper over your head or whatever you had. And we watched this silly little cartoon about Bert the Turtle. And there was a little ditty that went with it. You know, ‘There was a turtle by the name of Bert, and Bert the Turtle was very alert…’

Even as a kid, I thought, if a bomb hits, ducking and covering isn’t going help me.”

Mary tours all over the world, advocating for international downwinder communities. She also wrote and produced a play about her own experiences, called Exposed. In a particularly charged part of the play, the actors playing Mary and her sister, Ann, have just gotten their hands on a copy of Carole Gallagher’s American Ground Zero, and a list of radiation-induced diseases it provides gives them pause.

Ann: Think of our old neighborhood. Remember Tammy Packard?

Mary: Of course, she died of a brain tumor, when we were little.

Ann: And then three weeks late her little brother died of—

Ann and Mary: Testicular cancer!

Mary: He was only four. How does a four-year-old get testicular cancer?

Ann: Mr. Howell, down the street. He died of a brain tumor. Terri Cantrell. She had a brain tumor. And LaDonne Montague, she had bone cancer…

Exposed wasn’t fiction. And the play ends with a reading of a list of the dead.

Mary outlined for me how she and her sister stumbled into popular epidemiology.

“As the years went on, I would discover more and more people from that neighborhood—which is a five block area of people—who had all sorts of things like radiation-related illnesses. There were autoimmune diseases, there was a lot of lupus. Other people have thyroid cancer. And I thought, okay, something happened to us. Something happened to all of us.

My sister and I started keeping a list of all these people. And this was in 2001. That list got up to 54 people. And my sister ended up being diagnosed with lupus, and she had the bad kind that that goes to your kidneys and your brain. And she had three young children and she ended up dying.”

In that interview for the Downwinders of Utah Archive, Mary described the idea that, for many, the Cold War was actively hot.

“We all grew up, in my area, anyway, trusting the government and trusting doctors and trusting authority. It was really hard to believe that they knowingly let that happen to us.

Essentially, there was a nuclear war. It was undeclared, but to me, that whole arms race was a nuclear war, because we killed our own. Russia killed its own. Everywhere they tested, they killed their own. And it’s very, very discouraging to think that your government will sacrifice you in the name of national security. It’s hard to ever trust them again.”

That traveling art show that I mentioned earlier, Exposure: Native Art and Political Ecology, was eye-opening. We’ll be hearing from several more of the artists in that show in upcoming episodes.

What has stuck with me about Exposure is how effectively gathering these artworks together in one space conveyed the devastating scope and scale of the nuclearized world, which otherwise feels so abstract, so much like a hyperobject.

Abandoned uranium mines on the Navajo Nation, the Great Lakes, and elsewhere.

The impacts of atomic energy on the Ainu people of Japan.

The faulty Runit Dome on the Marshall Islands.

The push to mine uranium on Greenland.

British nuclear detonations in Aboriginal Australia.

Communities nuked in Eastern Kazakhstan.

French nuclear detonations in Polynesia and Algeria.

The Hanford site’s contamination of the Columbia River in the Pacific Northwest.

Samoans recruited into the the US army

The psychological impacts of nuclear saber-rattling between the US and North Korea on the people of Micronesia.

The legacies of nuclear detonations, uranium mining, and energy disasters span the planet. Radiation knows no borders or timelines. It remains an ongoing, global threat.

When the Covid-19 pandemic moved events online, there was a silver lining: downwinders worldwide could finally connect. The shift to accessible video conferencing allowed nuclear-affected communities to see and hear one another in a way they never had before.

Tina Cordova explained her own experience with this, when we met up in Santa Fe in June 2024.

“When I met a young woman from Tahiti, I was like, she could be my daughter. She looks like me. We look similar, you know? And I, I remember thinking, why do we all look so much alike?

And I never discovered that, Sean, until COVID and we were doing stuff by Zoom. All of a sudden I can get on Zoom with somebody from Kazakhstan, and the first time I was on one of these Zoom meetings, and they had downwinders from all across the world—Aborigines from Australia, and the Polynesian people, and the Marshallese—and I'm going, they look like my cousins from Tularosa.

And then it was like… it's not accidental.”

If you’ve valued reading Time Zero and want to support my research, you can subscribe below (or upgrade to a paid subscription):

If there’s anyone you think might be interested in Time Zero, please share:

Le Zotte, Jennifer. “How the Summer of Atomic Bomb Testing Turned the Bikini Into a Phenomenon.” Smithsonian Magazine. 21 May 2015.

Kluge, P. F. "Micronesia: America's Troubled Island Ward". Beacon Magazine of Hawaii, via Reader’s Digest (pg. 161). December 1971.

Brown, April L. “No Promised Land: The Shared Legacy of the Castle Bravo Nuclear Test.” Arms Control Association. 2014.

Pohle, Camilla. “‘Ashes of Death’: The Marshall Islands Is Still Seeking Justice for US Nuclear Tests.” The Diplomat. 01 March 2024.

As stated in previous installments of Time Zero, this figure of 250,000 deaths, over time, is what I believe to be a relatively conservative estimate, based on a wide variety of sources, including: The International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons. “Hiroshima and Nagasaki Bombings.”; Wellerstein, Alex. “Counting the dead at Hiroshima and Nagasaki.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 4 August 2020.; National Archives. “The Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.”; and multiple other sources.

Atomic Heritage Foundation. “Klaus Fuchs.” National Nuclear Science & History Museum.

“Russian Atomic Bomb Shakes UN Assembly.” British Pathé. 1949.

Alvarez, Robert. “Operation Crossroads: ‘The World’s First Nuclear Disaster.’ The Washington Spectator. 29 May 2025.

“Edward Teller - Checking the explosions on a seismograph (Part 1) (112/147).” YouTube, uploaded by Web of Stories - Life Stories of Remarkable People, 26 September 2017.

“Edward Teller - Checking the explosions on a seismograph (Part 2) (113/147).” YouTube, uploaded by Web of Stories - Life Stories of Remarkable People, 26 September 2017.

Jose, Collen with Kim Wall and Jan Hendrik Hinzel. “This dome in the Pacific houses tons of radioactive waste – and it's leaking.” The Guardian. 3 July 2015.

Rust, Susanne. “How the U.S. betrayed the Marshall Islands, kindling the next nuclear disaster.” LA Times. 10 November 2019.

Edel, Charles and Kathryn Paik. “The Compacts of Free Association, Congress, and Strategic Competition for the Pacific.” Center for Strategic and International Studies. 31 January 2024.

Gold, Jenny. “House Health Bill Would Help Pacific Island Migrants.” NUNM/NPR. 6 January 2010.

Rust, Susan. “Decades later, Congress restores Medicaid for Marshallese and other Pacific Islanders.” LA Times. 21 December 2020. Last updated: September 2023. Accessed August 2024.

Louka, Elli. “Marshall Islands Nuclear Claims Tribunal.” Oxford Public International Law.

“Nuclear Justice.” The Bikini Project.

“What is a nautilus?” National Ocean Service.

Kapahua, Kawena'ulaokalā and Joy Lehuanani Enomoto. “US Pacific War Games: Enlisting Global Forces for Imperialist Domination.” Sri Lankan Guardian. 17 July 2024.

“Contested Landscapes: Sacred Places.” Nevada Test Site Oral History Project. University of Nevada, Las Vegas. University Libraries Digital Collections.

McKeon, James. “Mushroom Clouds That Never Vanished: The Fight to Secure Compensation for Nuclear Test Victims.” Nuclear Threat Initiative. 9 November 2023.

Schofield, John with Colleen Beck and Harold Drollinger, H. “Archaeologists, activists and a contemporary peace camp,” 2009. In Piccini, Angela and Cornelius Holtorf (Eds.), Contemporary Archaeologies: Excavating Now (pp. 95-112). Switzerland: Peter Lang Group, 2011.

Williams, Terry Tempest. “Witness to the Cold War in the desert.” High Country News. 01 June 2022.

Karabaic, Lillian and Winston Szeto. “Documentary ‘Downwind’ shows deadly consequences of nuclear testing on tribal lands.” Oregon Public Broadcasting. 21 January 2024.

“Kodak film fogged by the Trinity test.” Oak Ridge Associated Universities.

Blitz, Matt. “When Kodak accidentally discovered a-bomb testing.” Popular Mechanics. 20 June 2016.

Focht, Maiya. “A secret bomb and ruined film: Why the US government only told Kodak it was going to test nuclear bombs.” Business Insider. 25 July 2023.

Downwinders and the Radioactive West. PBS. 2022. 25:14-25:35.

Ibid. 25:45-26:05.

“Nuclear Fallout Impacts to the Western Shoshone Nation.” YouTube, uploaded by S Behl. 15 April 2019.

Alexander, Thomas G. “Radiation Death and Deception.” Utah History to Go.

Thorough knowledge of the dangers of radiation were well-known and documented long before atmospheric detonations began at the Marshall Islands or the Nevada Proving Grounds. Among multiple sources, a particularly profound examination is by James L. Nolan, whose grandfather was one of three key medical personnel overseeing the Manhattan Project. See: Nolan, James L. Atomic Doctors: Conscience and Complicity at the Dawn of the Nuclear Age. Cambridge: Harvard University Press (Belknap). 2020.

Kite, Allison. “Records reveal 75 years of government downplaying, ignoring risks of St. Louis radioactive waste.” Missouri Independent. 12 July 2023.

Edmonson, Catie. “Senate G.O.P. Includes Expanded Fund for Radiation Victims in Policy Bill.” New York Times. 12 June 2025.

Benen, Steve. “Senate Republicans’ megabill is even more brutal than the House’s version, CBO says.” MaddowBlog, MSNBC. 30 June 2025.

Stone, Mike and Jeff Mason. “Trump selects $175 billion Golden Dome defense shield design, appoints leader.” Reuters. 20 May 2025.

“Baby teeth left from historic study now part of new study.“ Associated Press. 27 March 2021.

Mangano, Joseph. “What Caused My Cancer? Radioactive Isotope in Baby Teeth May Be a Clue.” The Washington Spectator. 8 September 2021.

“World Wakes Up to Horrific Scientific Survey.” ABC News. 07 June 2001.

“The Conqueror: The story of the most toxic movie in Hollywood history.” Yahoo! Movies UK. 09 November 2016.

Cook, Emily. “Downwinders in Court: Irene Allen v. United States.” Intermountain Histories. 19 May 2018. Accessed 13 April 2024.

Bauman, Joseph. “‘Dirty Harry’ Put Radiation Needle off the Dial.” Desert News. 28 October 1990.

Ibid.

Rafferty, Kevin with Jayne Loader and Pierce Rafferty (Dirs). The Atomic Café. 1982.

Cummings, Judith. “Three Decades After Bomb Tests, Utah Sheep Ranchers Feel Little; Bitterness.” New York Times. 15 August 1982.

Bauman, Joseph. “Justice still eludes sheep ranchers.” Deseret News. 5 November 1990.

Seegmiller, Janet Burton. “Nuclear Testing and the Downwinders.” Utah History to Go.

“Downwinders Interview with Mary Dickson (January 11, 2017).” YouTube, uploaded by GIS Services at the J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah. 03 October 2017.