04: Wastelanding / Part 02

If you give the monster a form, it is subject to entropy. It can die.

You can listen to this episode for free on Apple, Spotify, YouTube, or wherever you get your podcasts.

You can also access (free) full essay versions at timezeropod.com.

Subscribe (or upgrade to a paid subscription):

04: Wastelanding / Part 02

In part one of 04: Wastelanding, we looked at how centuries of uranium mining in Europe had made abundantly clear the dangers that this extractive industry posed to miner health1. By the 1930s, cancer from uranium dust was officially recognized as an occupational hazard in Germany and Czechoslovakia2.

But when uranium extraction began on Native lands in the 1940s, none of that knowledge was shared. Navajo and Laguna Pueblo miners were given no protective gear, ventilation was minimal (to nonexistent) and their families were left exposed to radioactive dust and contaminated water. Even washing work clothes by hand became a source of toxic exposure34.

In July 2024, I spoke over video chat with Dr. Chip Thomas, who had recently retired and moved to Flagstaff, AZ.

“For 36 years, I was based 2 hours and 15 minutes northeast of Flagstaff out on Diné Bikéyah, or the Navajo Nation, working as a primary care physician.”

By the time that Chip arrived on the Navajo Nation in 1987, the longterm effects of uranium work had become apparent.

“A lot of these men had chronic upper respiratory illnesses that reduced their lung capacity. And they were on chronic O2. There were some people who came in with respiratory and renal cancers, from their work in the mines. They needed to get checked every six months, to continue receiving benefits from the Department of Labor.

And hearing their stories sensitized me to the lack of instruction, and the lack of empathy, that the government, as well as the private mining corporations, demonstrated while extracting this material, uranium, from the Four Corners area.”

For twenty-plus years, in fact, rates of lung cancer and respiratory diseases had been surging. And this was particularly noteworthy for this specific population.

“When US public health officials went to the Navajo Nation in the 1950s, it may have been in the 1940s, it was thought, because cancer rates were so low, that Native people, especially the Diné, or Navajo, had a gene that prevented them from getting cancer. However, within 12 or 20 years from that time—so, by the mid-1960s or late 1960s—rates for some cancers were twice the national average.”

The government and extractive industries don’t simply have a history of lacking empathy. To this day, they continue to violently exploit natural resources on Diné land.

“At the end of August 2023, when I left the Navajo Nation, 25% of my patients still didn't have running water or electricity, despite having, on their land, an abundance of natural resources including coal, oil, natural gas, uranium, water, and aquifers. This should be the richest place in the country, right? With, if they wanted it, streets paved with gold—or at least every home having running water and electricity. But that’s not the case.

The Navajo Nation is roughly 27,000 square miles in size. It’s home to roughly 180,000 people. It’s not necessarily densely populated, but it’s larger in landmass than 10 individual states. It’s larger than the state of West Virginia.

Sadly, Diné Bikéyah, or the Navajo Nation, can also be used as a case study for neocolonialism, in that the wealth of the nation is not necessarily coming back to the people, but it's going to multinational corporations.”

The Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA) was signed into law by President George HW Bush on October 15, 1990. The act provided partial financial compensation to select populations of people impacted by nuclear industries during the Cold War. It also formally apologized to said populations.

Uranium miners who developed lung cancer, or other specific respiratory diseases, were eligible for a one-time payment of $100,000 through RECA. This only applied to miners who worked in the industry up until 1971, when the government quit buying uranium. Very recently, it bears mentioning, the Trump administration’s One Big Beautiful Bill was passed with an expansion of RECA included among its many provisions. Miners, millers, and transporters who worked up to 1990 can now apply for benefits, if they got certain types of cancers.

Since the 1990s, though, the byzantine application processes have proved difficult to navigate for many cancer-stricken Navajo miners, who were denied from the program. Deceased miners’ families were identified as beneficiaries in the program, but many were also denied, since surviving spouses, married through traditional Navajo ceremonies, didn’t have paper marriage licenses.

And it was difficult for Navajo to trust RECA on a fundamental level. The very agency that had vehemently opposed the establishment of the compensation program, the Department of Justice, became the administrator of the program.

In our third installment, A Low-Use Segment of the Population, folk historian Sarah Fox, author of Downwind: A People’s History of the Nuclear West, spoke with us about who typically spearheads environmental justice movements in the United States.

Wastelanding author Traci Brynne Voyles echoed Fox’s perspective.

“They are disproportionately led by women,” Traci told me, “and particularly women of color and Indigenous women.”

Navajo women were integral to the passing of the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act. Cast off by the United States government and health officials, Diné women documented illnesses and deaths from uranium mining, engaging in popular epidemiology. That’s the same community-based science methodology undertaken by the women near the toxic Love Canal, New York; in the Tularosa Basin where the Trinity bomb was exploded; or in the Mormon communities of southwestern Utah, downwind from the Nevada Test Site.

Traci elaborated.

“One of the things that is certainly true when you look at these cases, on the ground, is that there are all sorts of ways in which gender shapes people's exposure to environmental harm. And that doesn't mean that the women are impacted and men aren't. Because that's certainly not true, especially in cases of workplace hazards in masculinist industries, where, for example, with uranium mining.

The gendering of environmental impact doesn’t mean that only women are impacted, it just means that gender shapes the different ways in which people are impacted.

For example, in the cases that I was studying, some of the early environmental activists in and around uranium mining were women because they were the widows of miners who had had massive health impacts, and often had died prematurely because of their exposures to radioactive harm in the mines. And so, simply by virtue of needing to get some kind of compensation, the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act was one of the first major pieces of legislation that uranium widows really pushed. And all of those very material problems have to do with why women come to step into these roles.”

And, to be clear, it took decades and tragic numbers of cancer diagnoses and deaths before the US government acknowledged the epidemiological work that those Navajo women undertook.

In addition to cancer, miners and their families also have much higher rates of tuberculosis, silicosis, and fibrosis, as well as birth defects5. There’s a fatal neurological disease among children called Navajo neuropathy, which is linked to mothers drinking uranium-contaminated water during pregnancy6. Radioactive contamination has no scent, no taste, and cannot be seen by the human eye. And radiation exposure can physically change one’s DNA, leading to intergenerational disease.

Consider the grief, the anxiety, and the fear of living in the place your family has called home for centuries, and constantly having to think about whether it might silently kill all of you. This is what Rob Nixon calls slow violence7, and, simultaneously, yet another example of Joseph Masco’s nuclear uncanny8. In the nuclearized world, one cannot trust one’s own senses anymore.

Central to Traci Brynne Voyles’s Wastelanding, is her argument about the ways that landscapes (and the communities that inhabit them) have come to be perceived by western extractive capitalism.

“Environmental injustices and environmental racism occur, in large part, because of the ways in which certain kinds of places are seen as protectable and certain kinds of places are seen as pollutable. So there’s a naturalization of environmental disaster in places are impoverished, or Brown, or Indigenous, or Black, that is not true in other kinds of places.”

Traci also explained a perceptual paradox of the nuclearized world, which has to do with the material (or mineral) realities of atomic technologies.

“The other thing that I think is a factor, is that when people think about nuclear energy or nuclear bombs, nuclear technology kind of writ large, they tend not to think about the uranium mining, right?

If nuclear bombs and nuclear energy are this futuristic new technology, then mining—a miner, down chipping away at an ore vein, with a hardhat on—is something that does not feel at all futuristic. And so I think that that kind of temporal privileging, of nuclear energy plants, which are all new and shiny at this time, and nuclear bombs, just means that uranium mining is not seen as part of the story at all.”

In May, journalist Jonathan P. Thompson reported that the Bureau of Land Management’s Monticello field office took just eleven days to approve Anfield Energy Inc’s proposal for Velvet Wood, a new uranium mine in southeastern Utah9. This highly unorthodox, truncated timeline precluded public input, tribal consultation, and even cursory reviews of the project’s environmental, cultural, and long-term economic impacts10.

Anfield still faces regulatory hurdles at the state level, and opposition from various communities is mounting, so the outcome remains unclear. As Thompson points out, though, having an extractive project like this on public lands so casually greenlit at the federal level is telling.

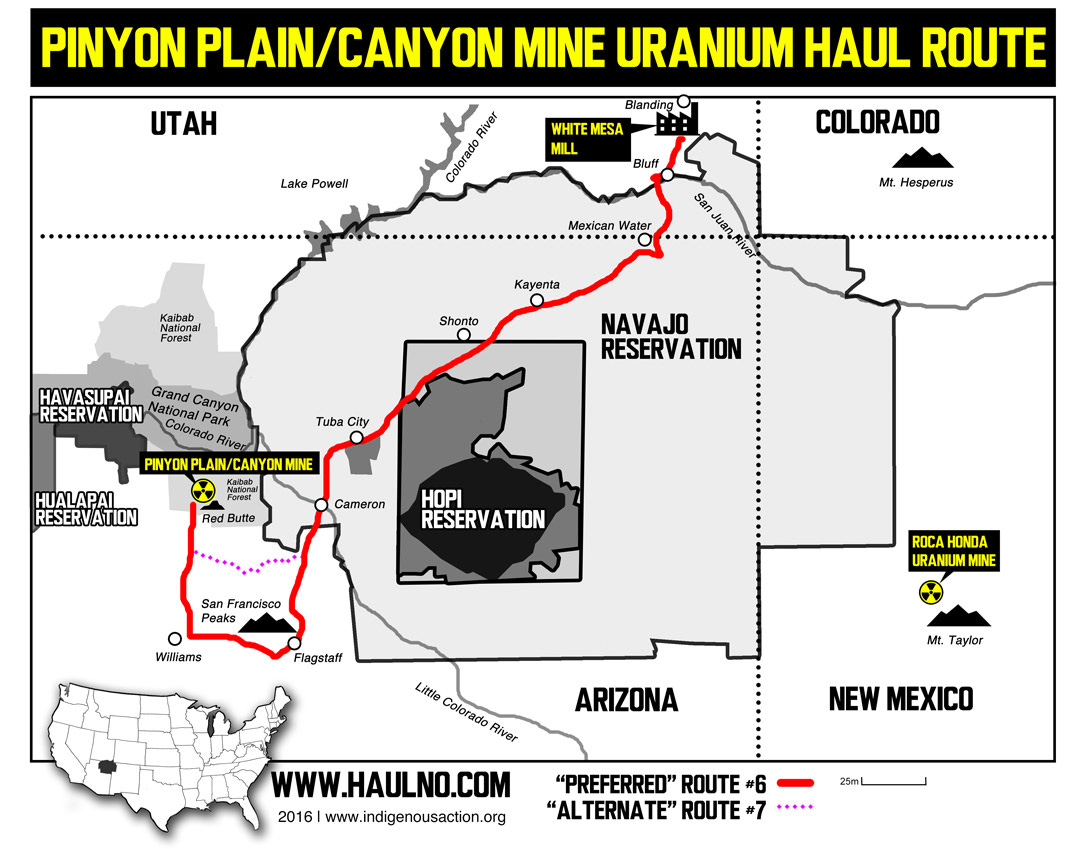

This isn’t unique, however, to the current administration. In December 2023, a company called Energy Fuels Resources, who is registered in Canada, but is headquartered in Lakewood, Colorado, a suburb on the southwest side of Denver, began extracting uranium just six miles from the South Rim of the Grand Canyon. This operation, the Pinyon Plain Mine, is located within the Kaibab National Forest, and inside the boundary of the Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni Ancestral Footprints of the Grand Canyon National Monument.

Pinyon Plain Mine is located just off Highway 64, which thousands of tourists travel daily to reach Grand Canyon Village. Just fourth miles south of the mine is Red Butte, a site that is sacred to the Havasupai tribe. Santa Fe-based artist and activist Shayla Blatchford, the force behind the Anti-Uranium Mapping Project, has traveled to the Pinyon Plain Mine to participate in and document protests.

On August 27, 2024, Shayla documented an impassioned speech by Diana Uqualla, a Havasupai Tribal Council Member.

“Everything upon this world depends on this Mother. So, why are we doing this? And on top of that, if that contamination hits our creek, it goes straight into the Colorado [River]. It goes down to the townships in Nevada, and California. All of the people are going to start getting sick. I hope that mining company has a lot of money, because they're going to pay for it, is what I say.

And also, on top of that, they're going to use this mine, or, this uranium, shipping it across the ocean. And what are they doing over there? They're having warfare. They're going to turn this stuff into bombs. So we're going to die that way, too, if we don't stop it. So I hope people that are out there understand how important it is for us to stop this mine.

We still have a chance today, because we are here as a people. We are here with one mind, and one heart, because you understand how beautiful this place is. Grand Canyon will never be, if this comes out. They’re contaminating all this area that these tourists are passing through. It's going to hurt the land. It's going to become dead, and wasted. There is not going to be any greenery. And nobody can go to Grand Canyon, and look at the sacred altar.”

Shayla reflected on Pinyon Plain Mine, when we spoke over video chat in early 2025.

“To have something like a uranium mine right next to [Red Butte] is just really devastating, and just so disrespectful. And not even to mention just the potential dangers and hazards that that brings to their community, that puts the water in danger. There are even studies that have been done so far that are showing that there's already some contamination, and an increase of uranium and other toxins in their water. And that can be found on the Grand Canyon Trust website.”

Back in 2012, the Department of the Interior issued an order that temporarily banned new mines for twenty years within a one-million-acre region surrounding the Grand Canyon11. So, how exactly does a private mining company get to decimate a landscape that is protected explicitly from their industry?

Well, we can thank the 1872 Mining Law, which was written to shield 19th-century private mining outfits from new laws or land protections1213.

Nihilistic legal interpretations of this law—which predates the invention of the typewriter, light bulbs, and toilet paper—argues that even though the mine itself was not a physical mine in 2012, when the mining ban was made law, its theoretical existence, since receiving a Forest Service permitting approval in 1986, meant it should be grandfathered in.

Here, we see a textbook example of the vampiric lens through which industrial-colonizers choose to view landscapes. Indigenous communities, industrialists have historically argued, are not using the land productively. Governments tend to agree. And so, in the interest of short-term profit, lands are seized, parceled out, and pillaged. They are, as Traci Brynne Voyles says, wastelanded.

According to the Havasupai, the Grand Canyon Trust, the Center for Biological Diversity, and other orgs, Pinyon Plain is only scheduled to be open for 28 months. During that time, it will satisfy less than 2% of America’s current uranium demand14. In only about two years, then, Energy Fuels will wreak permanent environmental devastation on the Grand Canyon—just to make a few parasites in Denver and Toronto a little bit richer.

Energy Fuels is also facing opposition from the Navajo, across whose lands the uranium ore is being trucked to reach Energy Fuels’s White Mesa Mill near Blanding, Utah. Indigenous-led activist group Haul No! states that Energy Fuels could transport up to 30 tons of highly radioactive uranium ore per day, with truck beds covered only by tarps, through Flagstaff, through some of the most populous areas of the Navajo Nation, and alarmingly close to Hopi and Ute territories15. The Haul No! website provides a wealth of additional information, including shareable assets, environmental impact facts, and ways to get involved.

Shayla expressed her exasperation at the establishment of a new uranium site in a landscape that is already scarred by more than 500 abandoned mines.

“To be working with radioactive material, just opening it up. What are we doing, as human beings? With all of just the stories, and things that I've come across, and the people that I've met and listened to, it's just a scary… I was going to say ‘element,’ but it's more than that. It is this monster.”

Late last June, just outside of Santa Fe, NM, I visited the studio of interdisciplinary artist Cannupa Hanska Luger. As I made my way up the gravel driveway, Cannupa came out to greet me, then walked me over to his three-story outbuilding studio.

On the ground floor, we weaved through chimerical figures that resembled superheroes, robotic bison, and interdimensional astronauts. Several of these were about to make their way to the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles. We climbed a staircase and made our way into the eagle’s nest, where I set up the mics. Cannupa offered a greeting in the Hidatsa language, then introduce himself in English.

“I’m Cannupa Hanska Luger. I am Awa'xe Dripping Earth Clan from the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara tribes in North Dakota. I’m Missouri River people. I’m also Lakota and European. And I am coming to you presently from Glorieta, New Mexico, which is customarily the lands of the Tewa and Towa people.”

Having grown up on the Plains, Cannupa moved to the Southwest years ago. He refers to himself as a guest. Out of the window below us was Glorieta Pass, a beautiful terrain covered in conifer trees, part of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. The conversation turned to monsters.

“When you break it down to its Latin, it means to warn: moneo. And so the idea of making something monstrous, for me, is kind of entangled in just the language of monster. And, as warning, customarily we had monsters, and we had monster slayers, in our stories.

Because I like fantasy and folklore, and myth and legend, as well as science fiction, I pay attention to all of these different models. And in paying attention to myths and archetypes across the globe, and in this recognition of monsters and monster slayers, I start to see these patterns that arise. More often than not, the demonic or the monstrous, in cultural contexts, are entities that are out of balance with everything else.”

“And so making that leap to colonialism, extractive and/or settler, to capitalism, to hyper-militarization, all of these things are grossly out of balance. And with that, with that gross out-of-balance-ness, they become monstrous. And if we recognize them as such, and and describe them as monsters, then they become a warning.”

Cannupa’s work is often described as a visual hybridization of Indigenous and science-fictional cosmologies. He inverts tipis, tricks out vans, and fabricates neon regalia. The work is electric, aesthetically, and charged with narrative. He personifies those monstrous entities, makes them into beings.

“For me, if something is an idea, it's ethereal. Entropy doesn't act on it the same way. It takes too long to change. But if you could present it as an organism, then entropy accelerates. And the only organisms that I could imagine these entities becoming, to us, are monsters.

Oftentimes, these monsters were participants in and a part of the society that you're operating in. And in these systems that we navigate, we can slay the monster, but we need to recognize that we've created it, that we've fed it, and that we continue to feed it. There’s something about being accountable to our support of these industries—and our perceived dependence upon them.

Without a name, it consumes all. But if we give it a name and we give it a form, then at some point you could be like, ‘I think you've had enough. You're plentiful.’”

Up above, you heard from Chip Thomas, a doctor who served the Navajo Nation for over thirty years. But when I introduced Chip, I left out an important detail. Chip is also known by the street art name jetsonorama.

Chip’s a unique guy. Not too many doctors have an art alias, or Chip’s origin story.

“In 1968 or 1969, in North Carolina, the public school system was desegregated, which led to bussing. With bussing in the South came a lot of violence. And as a somewhat shy only child with a stammer, my parents didn't really want me in the public school system.”

His parents considered sending Chip to military school, until they found the Arthur Morgan School in the Black Mountains of western North Carolina, a Quaker boarding institution with small class sizes, an emphasis on community-building and a darkroom.

“The first time I got the chance to go into a darkroom was my eighth-grade year. After that, I got my mom to buy me a manual camera, a Topcon. And I started shooting black-and-white film.”

That camera—and that school—changed Chip’s life.

“I would venture to say that we wouldn't be having this conversation now, were it not for the Arthur Morgan School.”

Eventually, Chip went to medical school at Meharry Medical College in Nashville, part of the Historically Black Colleges and Universities network. His dad had gone there. Chip got his school paid for as part of the National Health Service Corp program, which meant that after school, he would need to practice medicine for four years in an underserved area.

A friend from Meharry was working at Inscription House Health Center on the Navajo Nation, and suggested that Chip try it out. He arrived in 1987, and fell in love with the place. For decades, he shot portraits of his patients and their families, whom he came to know intimately.

On Navajo Nation, families often sell handmade jewelry at roadside stands. Plenty of tourists visit Monument Valley and Canyon de Chelly, or pass through on their way to the Grand Canyon, Lake Powell, or Zion. In 2009, Chip started wheat-pasting large-scale prints of his portraits on these roadside stands, which caught motorists attention.

By 2012, Chip was inviting other well-known artists out to the Navajo Nation to meet the communities and to create murals. He called it The Painted Desert Project.

“The Painted Desert Project was me inviting some of the biggest names in street art in the world at the time out to the Navajo Nation to spend at my home. And to spend time with people, getting a sense of their realities. And then we’d create a mural on roadside stands, or whatever walls I could get access to.

I tried to sensitize people to life on the Navajo Nation. I’d send articles and books and movie links for them to check out, prior to their coming. So it was like a mini-residency, a mini-social practice residency, for folks.

It was self-funded. And I ran it from 2012 to 2022. But it was also a residency for me, because, not having gone to art school, it was a wonderful opportunity for me to learn how people approach their art practice.”

Chip reflected on the original motivations behind installing his large-scale portraits of Navajo community members.

“It's been important to me, in putting up material on the roadside, to reflect back to the community the beauty, and the strength, that they shared with me during the 36 years that I was out there.

And what I would say to people, when I talked about my art project, is that when I saw folks in the clinic as a physician, as a primary care doctor, as a family doc, my objective was to create an environment of wellness within the individual so that they can realize their aspirations, their dreams—spend time with grandkids, great grandkids, whatever they want to do. And in reflecting the beauty of the community back to the community, I was trying to create an environment of wellness in the community. That was a complement to my medical practice.

Being African-American, people talk about Black joy, so I was attempting to celebrate Diné joy, Diné happiness.

One of the nicest compliments I ever got was a patient who came in, a young man who came in with his grandma, who was only Navajo-speaking, so he translated for her. But as they were leaving, he said, ‘You know, when we’re driving down the highway and my grandma looks over, and sees a picture of sheep over on one of those buildings, she gets a big smile on her face.’

People would sometimes ask me, ‘So, what effect, what impact, has this art project had on the people there?’ And it’s like, I don’t necessarily know the metrics for that, other than happy grandmas.”

“My name is Mallery Quetawki. I’m from Zuni Pueblo. I’m from the Badger Clan and the child of the Turkey Clan. I’m a Zuni artist. And I work in the intersections of art, science, public health, and medicine.”

I met up with Mallery Quetawki in May 2024 at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, where she is the communications and outreach specialist in the Community Environmental Health Program. At one point in our conversation, we found ourselves on the topic of monsters.

“This is from the Chaco Canyon area, and I’ve heard it from a couple different cultures that are ancestrally related to the Chacoan people—the ancient Pueblo peoples, my people—some of the prophecies that were shared, that could happen in the future. And this one seemed to have come true. I mean, it did.”

Mallery was recounting Pueblo and Navajo stories that warn about a yellow monster living beneath the earth in the Four Corners, stories that predate North American uranium mining by, at least, centuries. These stories are given a nod in Leslie Marmon Silko’s celebrated novel Ceremony (1977), about a traumatized World War II veteran returning home to Laguna Pueblo—where Eldon and Curtis Francisco live. Yellow Dirt is also the title of Judy Pasternak’s exhaustively researched and heartbreaking 2010 book about uranium mining in Navajo territory.

“One story I heard was that the reason in why Chaco Canyon would, you know, be abandoned one day is because there's something beneath us, something beneath there that if it came out, they almost describe it almost like a monster of a being, that if it came out, it was going to create a war between the children of the Earth.

It was going to create sickness, upheaval. So we should leave it alone. Leave it in the ground. Do not disturb it. It's part of the reasons why they might have left the region.”

From both biological and spiritual perspectives, the dangerous yellow dirt that is uranium can be understood as a material inversion of the life-giving yellow corn pollen that is sacred to the Diné people. The Diné called the buried yellow dirt leetso, which is said to translate approximately to reptile—or even monster16.

If you’re thinking that leetso sounds strikingly similar to Yé'iitsoh, the giant monster slayed by the Hero Twins that Will Wilson mentioned at the top of this episode, you’re not alone. The abundance of uranium in the vicinity of Mount Taylor, where Yé'iitsoh was felled, makes this rhyme all the more narratively compelling.

As Mallery mentioned, she’s from Zuni Pueblo, 90 miles west of Albuquerque, and adjacent to the Grants Mineral Belt, where so much uranium mining occurred in New Mexico.

Today, Mallery works frequently with other Indigenous groups—Diné, Pueblo, Crow, and Cheyenne River Sioux—whose landscapes and physical bodies have been impacted by the Cold War nuclear weapons chain.

Prior to bringing Mallery on board, the University of New Mexico, like so many American institutions, was struggling to build a trust-based relationship with Native communities. But Mallery’s background, demeanor, and—importantly–her paintings, have been bridging some of those historical gaps.

In bold, colorful acrylic works, Mallery paints Plains medicine wheels, Navajo wedding baskets, and turquoise, as well as bears, war ponies, and buffalo that serve as metaphors for the body’s pathogen-fighting B cells, T cells, and macrophages.

Her paintings have become cross-cultural translation tools, depicting human cellular networks in ways that can be understood culturally and spiritually.

“I want to see what it looks like if we can get all those people in a room together, even if each individual doesn’t hold all the same ideas. They all bring something very beneficial to the table.

I want to bring artists together, traditional home artists, people who are still in their communities, who have that voice, who have that power to record their community, their culture. And I want Indigenous scientists and non-Indigenous scientists to be able to work together, with an artist and with cultural knowledge holders. These people who are still living this experience, and are sharing in our teaching, our youth, and us.”

When it comes to building effective systems of care for Native communities, Mallery insists that western medicine should be seeking the perspectives of Indigenous artists and knowledge holders.

“They have such a deep, deep knowledge of their community and their culture, how important they can be to science, to research, to medicine, so that these services that the hospitals and clinics give us was made for us, by us, to inform these places.

And I want to empower people that way. The work that I'm doing now, I continually see more need in places, in public health, in institutions that need to change before I can even begin providing directly to my people.”

In one of Mallery’s paintings, Placental Transfer (2019), a newborn is connected to the landscape by an umbilical cord that morphs into the traditional hand woven sash belt worn by Pueblo and Navajo peoples. Whenever non-Indigenous people ask: If the landscapes have been poisoned and now pose danger, why don’t Native groups move somewhere else? She cites the painting.

“We are stewards of this land when we're born. That umbilical cord physically might be cut from our mothers, but now it's sewed into the flesh of the earth. We will never part with this land. We're born here. We die here. We return. We know we're a part of the soil. We become a part of nature. We become a part of the movement of the world, the balance, the harmony. Literally, when we die, we become part of the soil.”

Those stories about Chaco Canyon that warned explicitly against the excavation of yellow dirt seem to foretell this ongoing madness of mutually assured nuclear annihilation, social and cultural paranoia, and horrific rates of cancer in the communities near mining and weapons sites.

Art practices can and do make the hyperobject of the nuclear into local objects, by showing us its components with clarity—making them graspable. Will Wilson’s drone photos of leviathan uranium holding cells are unambiguous and direct. So are Carole Gallagher’s photographs of downwinders dying from cancer.

Equipped with this knowledge, though, we must then be able to think on a larger scale, one beyond our individual bodies or human-sized timelines. We have to cast the nuclear as a monster, what J Robert Oppenheimer himself, quoting from the Bhagavad Gita, called a “destroyer of worlds,” what the Diné call leetso.

By holding these two views simultaneously—by considering expanded ideas of time, and entertaining the humbling notion that we are part of a comprehensive, multi-temporal, ecosystemic body that is both flesh and landscape—we are capable of stopping this nuclear insanity.

We have unequivocally demonstrated that we are incapable of living alongside this monster. Uranium mining has to stop.

What do you think is the end game here?

The video embedded above, Breath of Wind (2017), was part of a 2017 exhibition called Hope & Trauma in a Poisoned Land. The group show, curated by Shawn Skabelund for the Coconino Center for the Arts in Flagstaff, AZ, also featured the work of Chip Thomas.

You’ve met the artist behind Breath of Wind in an earlier installment of Time Zero. We spoke by video in August 2024.

“My name is Anna Tsouhlarakis. I’m an enrolled citizen of the Navajo Nation, also of Greek and Creek descent. I was born in Lawrence, Kansas, but grew up between there and New Mexico. And my family is from the New Mexico side of the Navajo Reservation.”

Notably, Anna Tsouhlarakis’s family land is adjacent to the Church Rock uranium holding ponds that burst open in 1979, sending 94 million gallons of radioactive water into the Puerco River17.

“When I talk about adjacent, I'm not talking like we're a couple of miles away or anything. It's right next to where I have family living.

And when it happened, the spill was not announced to the surrounding communities. It was pretty much covered up. I don’t think that the people understand. And even my own family, I don’t think that they understood how big this spill was.”

Despite the spill, the Church Rock uranium holding ponds weren’t cleaned up or relocated. Will Wilson shot a stunning drone image of them in 2019. I went there last summer. They are enormous, and cartoonish in color.

“In my childhood memory, there were these two perfect football-field-sized areas that were bright green in this very arid landscape. And they always had sprinklers going on them.”

Nobody talked about the spill, so Anna had no idea what these were.

“The devastation… it definitely isn’t explained or understood. I went away to Dartmouth College, and it was in an intro level Native American studies class where we were talking about these environmental disasters across the country.

And I wasn't really paying attention during a lecture, and all of a sudden I heard somebody say, ‘Church Rock, New Mexico.’ And I was like, whoa, wait, that's the tiny little village that's right near where my family's from. Then I listened to the professor and he starts talking about the uranium spill and how big it was compared to Chernobyl and Three Mile Island.

I was like, wait, what? I had no idea that that had happened there. And at that point I was probably 19 or 20, and that's how I learned about it.”

In Anna’s video Breath of Wind, there is footage of Anna’s family land. Parts of it held houses. There are areas where, Anna says, she and her cousins played basketball. Other sections seem more remote. Throughout the video, you can deduce that most of the land is now vacant, what Anna describes as “overrun with tumbleweeds.” One of the most arresting aspects of the video is the sound of the wind.

“The wind was recorded on site. Then there are also recordings of my grandmother, who was the last monolingual Navajo speaker in our family. When I was born, and as I was growing up, there were several monolingual Navajo speakers in our family. But she was the last. And she passed away a few years ago.”

Whenever Anna was home from college, she’d record her grandmother telling stories in Navajo.

“It’s funny because, looking back, my aunts and uncles and parents all thought I was this weird art kid coming back and just bothering her. But in retrospect, I’m so glad that I did all that. Because we have her voice. We have her stories.

One of the stories that she was telling me, she was talking about how her sister went to boarding school in Oklahoma. They took her away, I think probably when she was kind of a 14, 15 year old.”

Her grandmother’s sister would write home about the tornadoes in Oklahoma.

“So my grandmother started talking about… what tornadoes are. And we have dust devils, or dirt devils, in the southwest.”

As Anna thought about making Breath of Wind, those dirt devils, whipping up particulates near Church Rock and other contaminated sites, kept surfacing in her mind.

“This entire time that I was growing up, and all my cousins were growing, and all my members were growing up in this place, that dust was always kicking up these toxic chemicals. It's constantly there. It's not dead. It's not just laying on the ground for nobody to ever be in contact with. It's in people's lungs.

And when we talk about dirt devils, dust devils, people say sometimes that those are evil things, witches that are coming towards us. I started thinking about those in terms of how they also hold this darkness in them.”

Anna layered footage of the landscape atop images of her own body, and scored the piece with the field recordings of the wind and her grandmother’s voice, everything overlaid at once.

“The video is the overlaying of imagery that is of the landscape, and also of my body. And it really is the intertwining of the two that I wanted to show. Because that darkness that is in the dirt—that’s in the sand and dust—it’s separate and it’s out there, but as soon as it gets breathed in, or in your eyes, or ingested, it’s part of you. And so, to me, the body and the land really is one thing.”

For Anna’s family, illness is not an abstraction.

“It's in me, it's in my body, too. I don't know if I'm going to get cancer. This is something that I am dealing with, is that very real possibility.”

Hope & Trauma, where Breath of Wind debuted in 2017, was billed as the first art exhibition to explore the impacts of uranium mining on Navajo land. As part of the exhibition’s structure, Anna, Chip, and other participating artists met with scholars, geologists, and other scientists from Northern Arizona University to discuss uranium mining. They also met community members on site visits around Navajo Nation.

Of course, both Chip and Anna were intimately familiar with the Navajo Nation. But, Anna said, the tours still proved eye-opening.

“One of the places we visited, there was literally a little kid's birthday happening outside of this trailer. And there were tons of people outside, celebrating, and the abandoned uranium mine was about 50 yards away.

That was devastating to see. This is not something that's in the past. This is not a historical issue. This is a very real and present issue that is not being addressed to the point that it needs to be addressed.”

Cold War-era uranium mining in North America wasn’t limited to the Four Corners region in the American Southwest. As mentioned in our first episode, the US government purchased defense program uranium from more than 4,000 since-abandoned mines across the west, scarring additional landscapes in Wyoming, California, Oregon, Nevada, Montana, and Idaho, and elsewhere18.

Anna was also part of that group exhibition that I mentioned in a previous episode, Exposure: Native Art and Political Ecology, which brought together an international roster of Indigenous artists producing work in response to nuclear legacies. She explained why it felt important to be included.

“Being in something like Exposure, that has artists from all over the world, you realize how many Indigenous communities are being neglected, in terms of our health and safety. And that it's not from 200 years ago, in the beginnings of colonial thought or colonization. It’s now it's it's very real. And it's not just us.”

Walking through the Exposure exhibition two summers back, I learned about uranium mining and nuclear weapons detonations on Indigenous lands on multiple continents. Everywhere, the playbook was virtually identical: make an aboriginal population dig out uranium, drop nuclear bombs on the lands of another one.

Copy-paste nuclear colonialism.

Today, the world’s largest uranium producer is Kazakhstan, which provides almost 40% of the global supply. During the Cold War, the Native Kazakh people were subjected to massive amounts of radioactive fallout from Soviet atmospheric detonations at Semipalatinsk.

And we’ve talked in earlier episodes about nuclear weapons used on Indigenous landscapes in the Pacific, North Africa, and Australia, that latter of which being where around 10% of the world’s current uranium mining occurs. Climate change is exposing massive, previously iced-over mineral deposits in Greenland—including uranium—which might help put a few things into perspective.

And, currently providing 22% of the world’s uranium, is our neighbor to the north.

Canadian uranium mining was originally incentivized by the US military’s ravenous demand during the Cold War. By 1959, there were almost two dozen uranium extraction sites across the Northwest Territories, Saskatchewan, and Ontario. That year, ore from those sites collectively generated $330M, making uranium the country’s most profitable mineral export19.

Last August, I got the opportunity to speak with another artist from the Exposure exhibition, Bonnie Devine.

“My name is Bonnie Devine. I'm a visual artist, a writer, and an educator. I was born in Toronto, and I was raised as an off-reserve member of the Anishinaabe of Serpent River First Nation, which is located on the north shore of Lake Huron.”

Bonnie is from Elliot Lake, Ontario, in Canada, not even 200 miles, as the crow flies, from my hometown in Northern Michigan. The 1950s Canadian uranium boom saw the establishment of a dozen mines near Elliot Lake, financed in part by extractivist and art collector Thomas Hirschhorn20, after whom the D.C. art museum is named.

As was happening simultaneously with the Navajo in the United States, members of the Anishinaabe First Nation of the Serpent River in Canada were intentionally excluded from decisions on how and where to extract uranium on their ancestral homelands. These very histories have influenced Bonnie’s practice.

“My work centers around the storytelling and image making traditions that are at the root of Anishinaabe culture. My practice combines written, sculptural, painted and performative gestures that explore issues of land treaty and history.”

After studying sculpture and installation art at the Ontario College of Art and Design University, Bonnie got her MFA from York University in Toronto.

“Despite that formal education, my most enduring influence and learning came from my maternal grandparents, who were trappers on the Canadian Shield in northern Ontario.”

In Exposure, Bonnie showed a 2015 installation work called Phenomenology. Leaning against the gallery wall were 92 hardwood stakes draped in muslin—a reference to uranium’s 92 protons and 92 electrons.

“A version of this piece has been shown outdoors. And when it's outdoors, these pieces of thin cotton muslin drift in the wind and replicate what I consider to be the wave action of an atom.”

In the gallery version of the piece, Bonnie mounts a small glass shelf to the wall.

“On the shelf, there was a chunk of gneiss, which is a metamorphic rock, a mineral composite rock that I collected at Serpent River First Nation, near the site of the uranium discovery. Metamorphic rocks are formed under intense heat pressure and chemical processes deep within the Earth. Metamorphosis is a process of transformation.”

What was placed next to that chunk of gneiss was particularly attention-grabbing.

“There is also a small tin container of uranium. It's labeled as such. And I just wanted to put together these two substances that are active. We think that minerals are inactive, inert, that they don't change, that they have no they have no capacity for reaction. And the opposite is true. It's just that it's so slow that we can't perceive it.

This phenomenon of metamorphosis is central, actually, because, as you approach the center of what I consider to be this field of activity, there is this notion of exposure. Oh, my God… I'm being exposed.”

The first time that Bonnie installed this work at the University of Toronto Art Gallery, fear of exposure prompted understandable concern from university authorities, who, Bonnie says, brought in Geiger counters and rigorously tested the work.

Bonnie knew that the amount she’d included didn’t pose a threat to visitors, but the immediate mobilization by administrators highlighted cultural inconsistencies about where, and upon whom, exposure seems to matter.

“That reaction, to this notion of exposure, to a dangerously active substance and our proximity to it, and how it activates within us a response, is such an interesting phenomenon. It’s contagious. This notion of radioactivity as a contagious property of matter. And how it can—by its ingestion into our system, our bodies—initiate a series of reactions in our own selves that are deeply, deeply harmful.

There is something more to this as well, which is the fact that when they began to mine the uranium out of the Canadian shield in the 1950s, they had zero regard for this notion of proximity to a dangerously active substance for the Indigenous population of the region.

And yet when you bring it into the city of Toronto and put it in an art gallery at the university, alarm bells go off on so many levels. We were we were in negotiation for several weeks about it.”

As Traci Brynne Voyles mentioned earlier, perspectives on landscapes are not innate. They are manufactured with intention.

“When I wrote Wastelanding, I was thinking about wastelanding as a process by which particular places come to be pollutable, to be seen as wastelands. And a huge part of that process is about mapping. It’s about visual representations of a landscape as empty.

One of my favorite scholarly fields to dabble in is cultural geography. And one of the things that cultural geographers write about is that while maps seem to represent a space empirically, they actually build in all kinds of epistemological worldview biases about what's important to see, or to not see, with a map.

What are the best ways to represent a space visually? Do you look at a space down from above or across a landscape, as though you're standing on it? All of these are different types of decisions that we just take for granted about how a space comes to be represented. I spent a lot of time in the book thinking about how the representation of places as pollutable, or as protectable, as wastelands or as places of value, really comes down to a lot of mapping projects, and ways of rendering a landscape visually.

In the uranium story, mapping was very, very important because what the prospectors and the Atomic Energy Commission were doing was mapping uranium deposits so that the prospectors and uranium companies could get to them, which entailed lots of just actual entry points onto the reservation by outsiders.”

Meaning, the AEC, prospectors, and mining corporations used maps to represent Indigenous lands as empty.

Throughout the fourth installment of Time Zero, we’ve considered numerous artistic, cultural, and community strategies for confronting nuclear industries. There are two that I think are particularly important in the pursuit of denuclearized futures.

The first is counter-mapping.

“Counter-mapping. in its most basic form, is a way for community members, Indigenous peoples, activists, to represent their own spaces, their own homelands, in ways that go against normative ideas of their space. Or try to represent their own kinds of world views of a particular place visually.”

Counter-mapping can include diverse strategies, especially when employed by artists.

These include Will Wilson’s drone photographs and smartphone app; Breath of Wind by Anna Tsouhlarakis; the public exhibitions and online land use database produced by the Center for Land Use Interpretation; Shayla Blatchford’s Anti-Uranium Mapping Project. Such critical art practices ask: If landscapes can be framed differently, why can’t futures?

The other strategy I want to underscore is naming the monster.

Giving the monster form, as Cannupa Hanska Luger points out, means that it is subject to entropy. It can die.

Moreover, monsters aren’t political, they’re demonic. They are a villain, a grotesquerie, an abomination that we can fight together in a spiritual battle instead of a culture war.

In the conclusion to Wastelanding, titled “Zombie Mines,” Tracy Brynn Voyles writes:

“We are indeed haunted by the ghosts, zombies, and monsters inherent to these apocalyptic technologies, and they do not stay put—they radiate out from polluted geographies in ways that insist on drawing new maps of toxicity”21.

Counter-map the terrain.

Name the monster.

I’ll close Time Zero’s fourth installment with what I found to be an especially interesting perspective that Cannupa Hanska Luger shared during our interview at his studio last June.

“Here's the reality of being a Native person in North America: Our apocalypse already came. This is post-apocalyptic.

So anything that I'm imagining, the future is only going to get better. The fire and the brimstone, the four horsemen of the Biblical apocalypse have come. And we survived it, those that are alive presently, by any means necessary.

So what's the big fear? What's what's scaring you so much? And mostly, it's death. And I'm like, dude, I'm not alive in the future world that I'm creating. As long as we maintain this constant fear of the inevitability of our own personal demise, we are going to pathologically harm generations to come.

It's like, dude, find a death doula. Find some way to be comfortable with your inevitable return. Love the fact that you are compost. You get to change. And all of this will, someday, end for you. But what it what did you leave behind?

I want to imagine and celebrate our future and I want to encourage generations because, I mean, I grew up with Mad Max and Terminator and all of these stories of some sort of like singularity that moves towards annihilation and desperate times.

And I'm like, only three generations into an apocalypse, maybe four, for my people. I'm talking like 1850s. By 1890-something is the heart of our apocalypse. My great grandmother was in it. That's not a long ago for me.

So let me imagine post-apocalypse, truly. Because I'm living it. Because this house that I'm in, the car that I drive, and the clothes that I wear, is the Mad Max universe that is sitting in the fear-space of everybody else.”

If you’ve enjoyed Time Zero and want to support my research, you can subscribe below (or upgrade to a paid subscription).

If there’s anyone you think might be interested in Time Zero, please share.

Benally, Timothy and Doug Brugge and Esther Yazzie-Lewis (eds.). The Navajo People and Uranium Mining, 26-27. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. 2006.

Ibid.

Pasternak, Judy. Yellow Dirt: An American Story of a Poisoned Land and a People Betrayed (pg. 208). New York: Free Press. 2010.

Voyles, Traci Brynne. Wastelanding: Legacies of Uranium Mining in Navajo Country (pg. 135). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. 2015.

Voyles (pg. 21; 110-112)

Pasternak (pg. 25; 283-284; 373-374)

Nixon coined this term to describe forms of environmental harm and social injustice that occur gradually and invisibly, and that unfold over time and space in ways that are often ignored by those in political power and mainstream media. See: Nixon, Rob. Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 2011.

As outlined in previous installments where Masco described his concept, the nuclear uncanny attempts to articulate the unsettling sense of disorientation that arises when everyday life becomes entangled with the invisible, radioactive, and potentially world-ending realities of nuclear technologies and infrastructures. See: Masco, Joseph. The Nuclear Borderlands: The Manhattan Project in Post–Cold War New Mexico. Princeton: Princeton University Press. 2006.

Thompson, Jonathan P. “A proposed Utah uranium mine gets the Trump treatment.” High Country News. 29 May 2025.

Thompson, Jonathan P. “Bureau of Livestock and Mining is back!” The Land Desk. 27 May 2025.

Memmott, Mark. “20-Year Ban Put On Mining Claims Near Grand Canyon.” The Two Way. KUNM/NPR. 09 January 2012.

Montgomery, Ellen. “Mining for uranium at the Grand Canyon.” Environment Arizona. 08 September 2024.

“Stop Pinyon Plain Mine: Protect and Defend Mother Earth Against Uranium Mining, Milling, and Transportation.” Indigenous Environment Network.

James, Loretta. “Uranium mining operations begin at Pinyon Plain Mine.” Navajo-Hopi Observer, 23 January 2024.

Voyles (pg. 160).

Wirt, Lauri. "Radioactivity in the Environment: A Case Study of the Puerco and Little Colorado River Basins, Arizona and New Mexico." Tucson, AZ: US Geological Survey Water Investigations Report 94-4192. 1994.

US Department of Energy. “Abandoned Uranium Mines Working Group Addressing Health and Safety Risks of Abandoned Uranium Mines Multiagency Strategic Plan.” PDF. 3 December 2022.

“History of Uranium Mining in Canada.” Canadian Nuclear Association. Archived from the original.

“The Elliot Lake Mining Camp.” Ontario Heritage Trust.

Voyles (pgs. 211-218).