Listen to this episode for free on Apple, Spotify, YouTube, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Access full essay versions of each installment at timezeropod.com.

Subscribe (or upgrade to a paid subscription):

If you’re reading this on the day it’s being released, August 06, 2025, it is the 80th anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima, the first time that a nuclear weapon was used in warfare. This Saturday, August 9, marks the 80th anniversary of the bombing of Nagasaki, the last time that a nuclear weapon was used in warfare.

Both of these actions were atrocities. Neither was defensible, no matter what the World War II fetishists, the military-industrial fascists, the op-eds freaks, or the broader commentariat will try to spin this week about the necessity of preemptive civilian mass murder to “save lives.”

Let us remember the hundreds of thousands of souls eradicated by these two weapons. And let us condemn, without qualification, not just the decision to use such weapons, but their very existence.

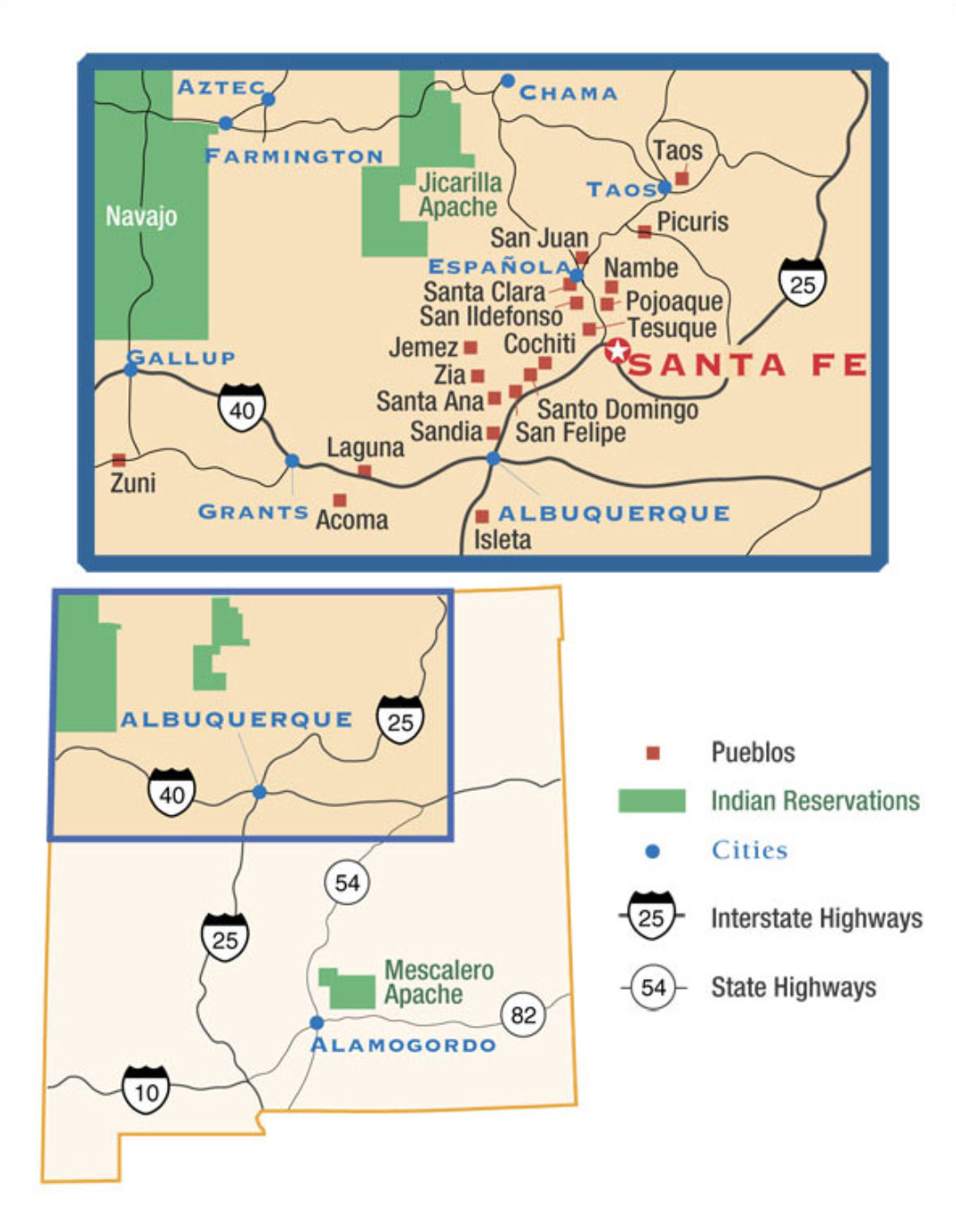

At the end of The Lab (Part 01), it was late morning on the Fourth of July, 2024, and I was up near Los Alamos National Laboratory with longtime anti-nuclear activist Joni Arends, who co-founded Concerned Citizens for Nuclear Safety in Santa Fe in the 1980s.

We were driving around White Rock, New Mexico, a bedroom community just below the Los Alamos lab. Less than a mile from an expanding White Rock suburban housing development sits Area G, a 63-acre site that is packed with radioactive and hazardous waste from the Manhattan Project and Cold War.

Joni pointed out roadside rock art depicting an avanyu, a water deity in Tewa culture, represented as a serpent1. Pueblo women, Joni says, who have tried to come up to the site to pray, have been stopped by armed guards from Los Alamos. From the car, we watched as White Rock families in White Rock went about their days casually and hikers parked at trailheads, as if Area G simply didn’t exist.

After such a spectacle, we needed a break. So Joni drove us down the hill to Pojoaque, where we hit the drive-through at Blake’s Lotaburger.

We found some shaded picnic tables at the nearby Poeh Cultural Center and ate lunch. The Poeh’s adobe tower structure is the studio and gallery of renowned Santa Clara ceramic artist Roxanne Swentzell, whose incredible figurative works in clay I used to go see again and again at the Heard Museum at Arizona State. I wrote two different papers on her in college. But the Poeh was closed for the holiday.

After lunch, we hopped back in the car to go see the Buckman Direct Division, a water intake on the Rio Grande, downstream from Los Alamos National Laboratory, where Santa Fe gets a sizable portion of its drinking water.

First, though, we were headed to pick up Joni’s friend, who met us at a highway pullout at the bottom of the Pajarito Plateau.

“I have a lot of different names. People know me as Sherry, Sheri, Serit. I get called a lot of different names. But my official name is Serit Inez Kotowski de Lopaz. I live in Taos, New Mexico and I'm a longtime artist. I’m 67, so I have probably spent at least 50 years of my life now as a practicing artist and dancer.”

I had seen Serit’s work before, in a 2023 exhibition in Las Cruces that we’ve covered previously: Trinity: Legacies of Nuclear Testing - A People’s Perspective, which was organized by the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium.

Serit showed a raku clay work called The Other Trinity Test Tower of 500 Souls, which paid tribute to the 500 people from the Tularosa Basin who had, by 2020, the year she created the work, died from cancers that locals attribute to radiation poisoning in the wake of the Trinity detonation.

As we ambled down the gravel road to the Buckman intake, Serit and I talked about another piece that she had in the show in Las Cruces, a three-part installation work called Sacred Trust: BROKEN, from 2019.

The installation included a cartographical drawing called the Sacred Trust Map which, Serit explained, was produced through a collective effort.

“The design was actually done by Deborah Reed Design, and Concerned Citizens for Nuclear Safety worked on it, as did Partnership for Earth Spirituality. There was a scientist from the New Mexico Environment Department, Carlos Bustos. We collected data. It showed all the toxic sites—how much toxicity is in New Mexico.

It covered nuclear sites. It covered gas and oil. It had all the mining, the delivery routes. It showed, basically, the extent of abuse of the land.

I think that most religions, or peoples that believe that there’s something greater than us, have a concept of the sacred trust, which is that the land we live on, it doesn’t belong to us. But we are responsible for taking care of it.”

For the installation, Serit had enlarged the map in black-and-white. She highlighted the Trinity detonation site by overlaying a green cloud, then superimposed a yellow cloud over bands of uranium mines. On the reverse side of the map, using silver point, she etched the words “Environmental Justice.”

Flanking the map were hand-built wooden shelves, holding two sets of ceramic dinnerware. The left set was colored green, a reference to Trinitite, the glass-like material produced out of sand during the Trinity explosion in southern New Mexico2. The other set was yellow, a reference to the uranium pulled from those mines in northwestern New Mexico.

“Being a potter, potters are associated with dinnerware. We make plates and cups. That’s kind of like the commonality. The message I wanted to put across was the pathway. How did these people get sick? We eat, we drink. These are all sustainable communities. They grew their own food, they had cisterns, they gathered water. They washed in the river. They live very close to the land. These people still live close to the land.”

Much of Serit’s other work has been a response to the environmental devastation that Los Alamos National Laboratory has produced, an ambient violence that’s always in the background for the people of New Mexico.

“You go for a hike, up in a canyon, a beautiful canyon, and it's contaminated from the nuclear weapons industry.”

After half an hour on dirt roads, we arrived at the Rio Grande. Joni parked the car and we walked over to the Buckman water intake. There were a group of people partying along the bank for the Fourth of July.

We surveyed the river, and Joni explained that both the city and county of Santa Fe get 40-50% of their water from this intake. Studies produced by the Department of Energy—not by activists—indicate that all surface water drainage and groundwater discharge from the Pajarito Plateau ultimately flows into the Rio Grande3. Meaning, whatever gets washed down from Los Alamos National Laboratory finds its way to the Rio Grande. Some of it discharges into the flow upriver from the Buckman intake, meaning that it’s potentially sucked up into the water that the people in Santa Fe are drinking. Radiation exposure, as we’ve covered before, is cumulative.

According to Joni, sometimes they stop the water diversion.

“If there are flows in the canyon, you know, at the bottom of where we drove up? If they sense that there’s flow in Pueblo Canyon, there’s a message that gets sent to turn this off or close these gates.”

Pueblo Canyon is the deep cut that splits the mesa into two. Serit offered that there are no such warnings for major water discharges coming down the other canyons. Joni agreed: there is no warning system for Water Canyon, or for the people living in Cochiti Pueblo, other other communities whose water comes from the Rio Grande, or who are otherwise in the path of water runoff from the Hill.

I asked if it made them nervous to drink the water in town. Serit nodded.

“It should. It should make people really nervous—and pissed off. Because the lab is doing this. And they don’t tell you. Or they go, “Oh, you know, it’s okay. It’s a little bit. Don’t worry.’”

When I spoke with anthropologist Joseph Masco in July 2024, he described the ways that people living and working in northern New Mexico are required to manage multiple strata of worries simultaneously.

“From a narrative point of view, it is super interesting when you are talking to people about what concerns them. I would have the experience, many times, of asking a question, let's say, about weapons work at Los Alamos. And I would get a story back that seemingly had nothing to do with weapons work at Los Alamos, but might have everything to do with worries about water, worries about air, worries about livestock, worries about animals, worries about food, worries about futurity, worries about citizenship, worries about who national security is protecting and who is it exposing.”

From this research, in his 2006 book The Nuclear Borderlands: The Manhattan Project in Post-Cold War New Mexico, Masco worked to articulate how people respond to the nuclearized world by borrowing from Freud’s notion of the uncanny—the idea of unhomeliness.

“The nuclear uncanny is offered as an invitation, actually, for conversation, to say that those things are really crucial to understand. And they're very much a part of the long term multigenerational effects of nuclear nationalism in the US. People lose track of their senses, they lose track of their temporal ordering.”

Since 1945—especially if you live near a nuclear site—you can never be sure what level of radiation you’re being exposed to. And everyone is always, potentially, just minutes away from nuclear annihilation.

“Danger itself becomes something that is both ever present and very ephemeral ,in terms of its qualities. And that's something that, of course, politically, is easy to manipulate as well. We’ve seen that, and are seeing that today.”

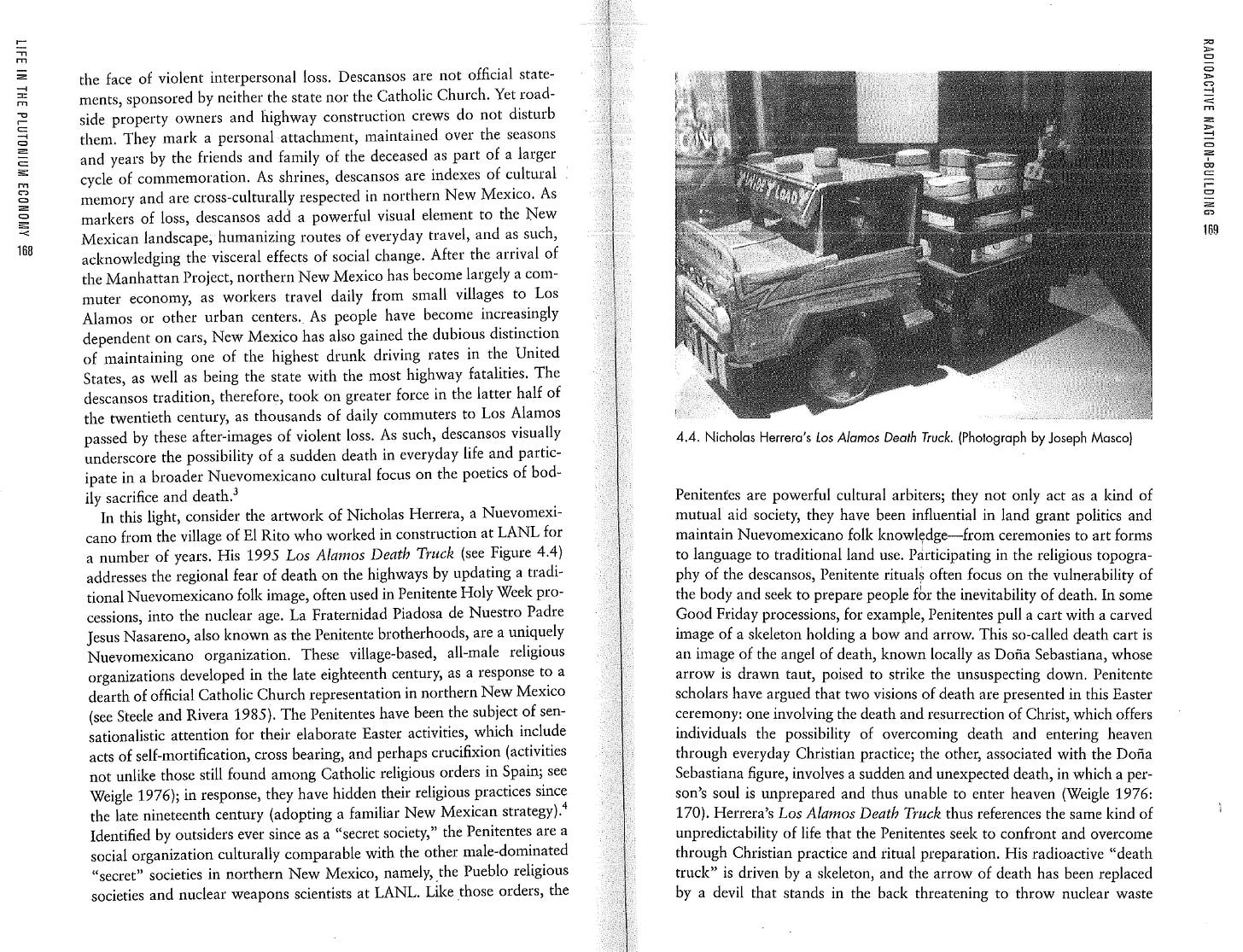

In Masco’s Nuclear Borderlands, in the chapter “Radioactive Nation-Building,” an image of a hand-carved wooden sculpture called Los Alamos Death Truck caught my attention. The artist, Nicholas Herrera, it turned out, lived very close to two friends of mine in northern New Mexico. What’s more: Nicholas’s girlfriend, documentary photographer Beth Wald, had recently shot their wedding. My friends introduced us over text, and a week later, in late May 2024, I was at Nicholas’s ranch. He showed me around the grounds, let me look around his studio and where he builds hot rods, and then we sat down in his comfortable living room to record an interview.

“My name is Nicholas Herrera. I’m here in El Rito, New Mexico. My family’s been here for six generations, on the original homestead. And I’m an artist. Never planned on it. Just happened.”

Nicholas is also frequently referred to as El Rito Santero—the Saint-Maker of El Rito, New Mexico.

“A santero is a saint-maker. Somebody who carves the saints, who paints the saints. I’m still a santero, but I’m like a modern santero.”

Los Alamos Death Truck is a riff on the death-cart, a ritual object pulled by the secretive Catholic brotherhood known as Los Penitentes during Holy Week processions4. This religious order is unique to the hybridized cultural communities of northern New Mexico and southern Colorado5. The brotherhood’s official name is Los Hermanos de la Fraternidad Piadosa de Nuestro Padre Jesus Nazareno.

Nicholas’s translation of the death-cart into sculpture, though, like so much of his work, is a bit of a departure.

“The older people would say, ‘You’re not supposed to have this over here, that’s not traditional!’ But there’s all kinds of people, all around me, they loved the piece. And I said, ‘This is the modern death truck.’”

He’s made a few different versions over the years, and described a Ford model.

“It's a big Ford. It’s got a tilt front end. And it's got the devil in the back smoking a cigar with a briefcase full of money. Because that's what it's all about: money. So he’s kicking back, you know what I mean?”

Surrounding the devil are, depending on the version, 55-gallon drums, filled with nuclear waste, or nuclear bombs. The truck, driven by skeletons, is ready to roll through Santa Fe, en route to the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant, or to Kirtland Air Force Base in Albuquerque.

“And the souls are in the front—the Hispanics are in the front. And they're all smoking cigars. Then there's a graffiti on the inside of the of the truck.”

Every piece of these sculptures is wood, carved by hand, and accented with paints that Nicholas pigments himself from local materials.

I’ve never seen the Ford model in person, but I did see one he made in 1995, the blue Dodge model that appears in Masco’s book (and in the video below) at the Harwood Museum in Taos last fall, during Nicholas’s large-scale solo show there, El Rito Santero. And last summer, at the Albuquerque Museum, I saw the 2003 green Chevrolet version pictured above.

“My great-great-uncle was El Santero de la Muerte. He used to carve angels of death for the Penitente Brothers, all around northern New Mexico. So it was my turn. That’s why I decided: Now I’m going to do mine. I’m going to do my death truck.”

Nicholas also learned about art from his mother.

“My mom was an artist. She didn't even know she was an artist, but she was. I used to hang with her a lot and we always had little projects going on. We'd go to the river, look for rocks. Go get glitter and glue. She kept me busy.

And she worked for a lot of these artists, too. She used to go clean their houses and I used to go with her and I used to get supplies. So we met a lot of really great artists. She encouraged me.

I mostly learned going to museums and I learned a lot of it on my own—and from other artists, too. I’d go to art shows and Spanish Market in Santa Fe, which opened up my eyes about art. Then I decided that I was going to move on. I started doing contemporary art.

I remember, I wasn’t supposed to do any contemporary art for a show in the Spanish Market, because it was all traditional. I did a truck called Desert Storm with nuclear bombs on it. And they were all freaked out on that.”

Nicholas’s relationship to Los Alamos National Laboratory was more than observational.

“I used to work in Los Alamos. I’d get up at 4:30 in the morning, and head up to Los Alamos. I worked up there as a laborer, I worked up there on the roads. There are places up there where you can’t put in a backhoe, so you’ve got to go in there and dig, and then do the work by hands.

When we worked on the roads, man, that was a trip. People were always calling us names, all kinds of racist shit. And I’d give everybody hell, too, because I didn’t take no shit.

They were gonna have to fire me one day, because some guy pulled up and I’m like, ‘You’re supposed to be 10 feet away from that sign.’ So, he just drove right up to me, and put his bumper right on my knee, and I told him, ‘You’re going to have to kill me today, because I ain’t going to move.’ And he bumped my knee, and I pulled out his wipers.

So, they took me to the red carpet, and I talked to the main guy. I think his name was Reynolds or something. And he goes, ‘Well, what happened yesterday, Nicholas?’

Because somebody called me to the office. ‘A man with an army jacket and a long braid is wanted in the office.’ And everybody looks at me.

So, I went over there and I had a meeting with him. And I told him why I did what I did. ‘Because these people treat us like shit, and I ain’t going to take no shit. You can fire me, if you want.’

And he got up, and he goes, ‘Well, I’m going to shake your hand. Because you told me the truth, and nobody talks to me like that.’

And I go, ‘What are you, Jesus, or what?’

I asked if the people who’d been hassling him up at Los Alamos were lab employees. They were, Nicholas said. Physicists, and the like. They were “in a different world.”

“And I’m an artist. I’d get home from Los Alamos at, like, five, six, seven, eight, nine, and work until 11. I could work for five more hours on my art, because I was disciplined. I was like, I ain't going to work up there. I want to quit that job soon, man. I'm going to work up there and then I want to do my art. I don’t know if I’ll make it or not but the first that I did, man, when I quit that job, I started showing my work everywhere. I started hustling. You’ve got to learn to talk, to talk shit, to get out there and survive.”

The Los Alamos Death Truck sculpture—and Nicholas’s art career more broadly—had a fittingly unorthodox origin. Nicholas’s girlfriend, Beth, nudged him to tell the story of how he got his first art show. He started laughing.

“That was a trip, because I ended up in jail in Los Alamos for a few months for running from the cops and a revoked license. I had been working up there a long time already. And so they locked me up for a while.

I was doing sketches in there, because there’s nothing else to do. I told the jailer, I’ll trade you some sketches for some cigarettes. I was drawing all kinds of stuff that I draw—cars and trucks.

The guard there was like, ‘Wow, I really like your sketches.’ All of a sudden, when I was about to get out of there, he said, ‘Well, my wife is a curator at the Fuller Lodge and she wants you to have a show.’”

Fuller Lodge is the large building in Los Alamos that was a central facility in the Los Alamos Ranch School before World War II, and later served as the dining hall and community center for physicists at Site Y. More recently, it has been a museum and cultural center for the City of Los Alamos.

“So, I was like, I ain’t messing this one up, man. That's a sign. Like, you've got to keep doing what you're doing. So that's when I did the Los Alamos Death Truck, because I wanted people in Los Alamos to see it. It was a big political statement. People loved it.”

I asked Nicholas if anybody else from his family had worked at Los Alamos.

“My dad worked up at the lab for a long time. He used to work in the machine shop. And sometimes he didn’t come home because he got contaminated. Sometimes, and they'd have to stay over there until… I don't know what they did. But he died of beryllium cancer.”

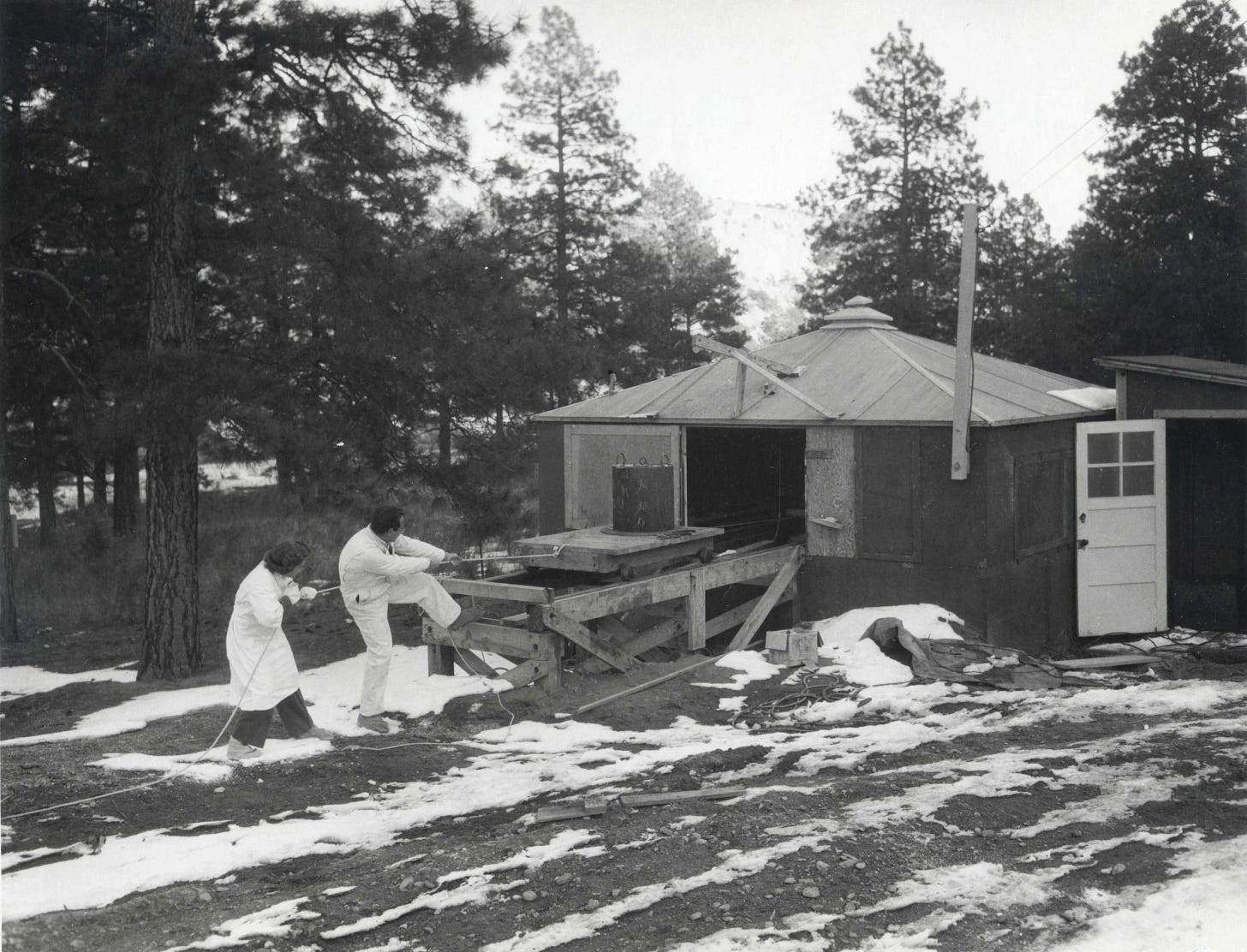

For good reason, the Trinity detonation on July 16, 1945, is seen as the birth of the atomic era. But Dr. Myrriah Gómez’s research complicates that seemingly straightforward account.

“I spent my sabbatical doing research on the radioactive lanthanum (RaLa) tests that happened in Los Alamos. There were 253 tests between September 1944 and 1962. So, over an 18-year period, 253 tests—or 254, depending on the source. There were almost two dozen tests that were conducted in Bayo Canyon in Los Alamos before the actual Trinity test.

Essentially, what happened is that the scientists working on the Manhattan Project realized that they couldn't use plutonium to build the same kind of bomb that they were using uranium in.”

The gun-type uranium weapon was, relatively speaking, a simple design: smash a hollow bullet of enriched uranium into a target made of the same material, and they’ll go critical, causing a chain reaction and subsequent explosion that’ll burn hotter than the surface of the sun.

But, as Dr. Gómez said, they couldn’t use plutonium in the same way. When you make plutonium in a nuclear reactor—as they were doing in Hanford, Washington—it ends up containing the isotope plutonium-240, which has a higher rate of spontaneous fission than plutonium-239. What that means is, if you shoot a bullet of plutonium at a plutonium target, the plutonium-240 contained in the material will fission prematurely, creating a fizzle, not a nuclear explosion6.

“Oppenheimer and Groves basically said, ‘We need to pivot. We already have all this plutonium. We've paid all this money to convert this plutonium, so figure out a way to use it.’”

Manhattan Project physicists soon came up with an implosion model, where explosive lenses would detonate a plutonium core or pit in on itself, creating the proper chain reaction. Plutonium was in short supply, but they were determined to test the implosion design, and chose to do so with lanthanum-140, a radioactive isotope of the earth metal lanthanum7, whose parent nuclide, barium-140, was a convenient byproduct of uranium enrichment. The half-life of lanthanum-140 is incredibly short, which made it optimal for such experiments. However, it still contains radioactive isotopes like caesium-140 and strontium-908.

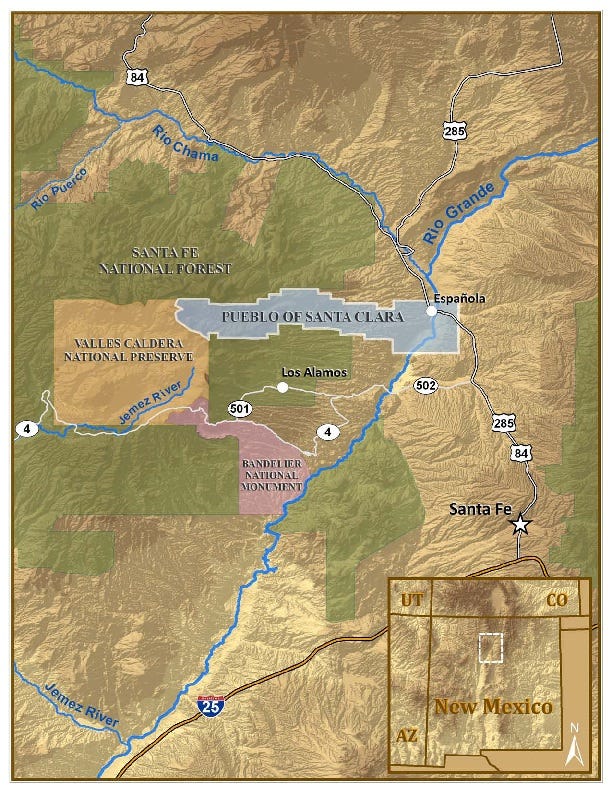

“They started doing all of these tests in Bayo Canyon, which is 8 miles away from San Ildefonso Pueblo, 11 miles away from Santa Clara Pueblo, 15 miles away from Española, and about ten miles away from my community in El Rancho.”

El Rancho is also home to much of choreographer Yvonne Montoya’s family. When Yvonne and I spoke in July 2024, she recounted the way that the Bayo Canyon detonations exist in whispers in El Rancho.

“No one talks about it—except for the elders that are no longer with us. I remember hearing stories from my dad, when I was a child, talking about how he would be driving at night through the area and all of a sudden the canyons would light up as bright as day.”

Dr. Myrriah Gómez elaborated.

“Nobody knew that this was happening. Nobody even knew nuclear. We didn't know nuclear weapons until Japan, right? Unless you were working on the project. Through these radioactive lanthanum tests, one of the one of the worst radionuclides that was released was strontium-90. And in some of the earlier studies, there was not a way to track the releases of that strontium-90.”

You may recall, from earlier installments, that strontium-90 is what the United States was quietly testing for in children’s teeth and cadavers, as they studied radioactive fallout from atmospheric detonations.

“Really, strontium-90 testing didn't start until they were using tracking for the atmospheric testing that was happening in the Pacific. They literally were using [Nuevomexicanos and Puebloans] as guinea pigs. So, my community—and our communities in northern New Mexico—were really the first ones to experience radioactive fallout. But you haven't heard that talked about at all.

The LAHDRA Project was probably the first document that came out, talking about the RaLa experiments.”

LAHDRA is the acronym for the Los Alamos Historical Document Assessment and Retrieval Project, which started in 1999. The Center for Disease Control brought on contractors to attempt a comprehensive inventory of over half a century of radionuclides and chemicals released by Los Alamos National Laboratory. The final report, published in 2010, is 638 pages long. It details a shocking amount of brazen contamination by the lab, and discusses the RaLa experiments, Area G, and plutonium work at Technical Area 559. You can download the full report here.

“And not to say that we can't and shouldn't talk about the Trinity test as the first, because it was the first scale bomb that was used—and used on people. There will never be another test like that in the world, because of the way it was conducted. But let's also talk about: it’s Trinity and the almost two dozen RaLa experiments that happened in northern New Mexico before that.”

Yvonne Montoya explained the legacies of RaLa, which sound eerily familiar to those we’ve heard about from residents in the Tularosa Basin.

“I have friends from high school whose grandparents are dying of the same types of cancers that my great aunts and uncles died of. My great-aunts and great-uncles were eating beans and squash grown in the valley, literally beneath the creation of the atomic bomb, where they were detonating stuff prior to Trinity.

Bayo Canyon is contaminated for thousands of years. And that was one of the canyons, that border where my great-great-great-grandparents had their homestead. And we're seeing stomach cancers. We're seeing liver cancers. They were eating this food that had to be contaminated. But that information is not being shared. There’s a lot of autoimmune stuff that’s coming up, cancer that’s coming up. And it’s not just contained in the Pojoaque Valley. I think it’s spread across the state.”

I first saw Nina Elder’s work in June 2024 in Nuclear Communities of the Southwest, the show organized by Alicia Romero at the Albuquerque Museum that we learned about in our last installment.

A month later, Nina and I met for an interview in Walsenburg, Colorado, just under 30 miles from where Nina had recently moved to, in southern Colorado. Nina grew up about 100 miles to the south, in the Pecos Mountains of New Mexico.

The day before I drove from Santa Fe north to Walsenburg, I was visiting photographer Will Wilson, whom you met in the Wastelanding (Part 01). When Will heard I was headed to see Nina, he quickly packed up a print he’d been meaning to mail out to her and sent it along with me. Small world.

Nina and I caught lunch at a café, and then moved to a dugout at a nearby baseball field, where we could dodge the July sun.

Almost immediately, we started talking about the 2011 Las Conchas wildfire, which had devastated the landscape around Bandelier National Monument, and then made its way towards Los Alamos National Laboratory.

“I was living north of Taos, very close to the land, and building with Adobe, which is local Earth that you mix with water. And because at that point I was drinking rainwater, I became really aware of my natural environment.

During that time period, there was a huge forest fire near Los Alamos, the Las Conchas fire. Everyone was terrified, because it revealed that the trees held this nuclear legacy that was being released through the smoke plumes. It was being released into the rivers. It was being released in every element.

And I thought, it’s always been here, since the uranium started getting disrupted and they started building bombs at Los Alamos, it’s always been here.”

Over the last 25 years, two major wildfires nearly consumed Los Alamos National Laboratory. The Cerro Grande fire, in 2000, caused by a prescribed burn at Bandelier National Monument, burned 43,000 acres, destroyed 400 homes, damaged lab buildings, and spread contaminants across nearby Pueblo communities.

When the Cerro Grande fire went out of control, Serit Inez Kotowski de Lopaz was living in Rio en Medio, in Santa Fe County, directly across from the lab.

“We could see the transformer towers exploding. I was taking care of a woman that had environmental illness, so I was very concerned about working to keep her safe from the smoke. I was also working at the rodeo grounds, taking care of the animals that were evacuated. And just thinking about the smoke and, well, that there was a nuclear weapons lab there, really, it was so frightening.”

Joni Arends talked about the Cerro Grande Fire, as we drove back down Highway 502 from Los Alamos towards Santa Fe. We were passing by Totavi, a very small, unincorporated area, near San Ildefonso Pueblo10.

“Before the Cerro Grande Fire, there were houses down here, next to the gas station, and I’ll show you the road sign.”

Totavi was established in 1948, as a trailer park for manual laborers, during the expansion of Los Alamos National Laboratory11. By summer 2024, besides that gas station Joni mentioned, Tewa Market & Fuel, I didn’t see any other buildings.

“We started asking about whether the maximally exposed individual, from the storm water, would be down here at Totavi. Then, all of a sudden, those homes were gone. The adobe homes were gone.

So they eliminated—as another example—eliminated the controversy. And here's the canyon. It's not very wide here, and it's not very deep, compared to the amount of water that would come down here, unmitigated.”

Massive forest fires destroy all sorts of natural barriers and absorption networks for stormwater. After the Cerro Grande fire, the amount of water rushing down the canyons on the Pajarito Plateau increased significantly, which meant that contaminants from the lab were even more broadly distributed down below.

Joni slowed the car.

“Here’s the sign Totavi Drive. There were four or six homes here. And because the water runs right over there, next to the bottom of it mountain, that's where we were raising that issue. And all of a sudden everything was gone.

I asked what had happened to the people who had been living in the homes, whether they had been moved somewhere after their houses were condemned. Joni frowned.

“I don't know. Before we raise issues publicly, we need to think about the consequences of raising those issues. Is it going to benefit anybody? Is it going to make it worse for somebody, depending on the situation? It's also a lesson, in terms of activism. Be careful what you ask for.”

In 2011, the Las Conchas fire—the one Nina Elder referred to—was sparked when a dead tree fell onto a power line. Nicholas Herrera also remembered the devastation, especially what came in the wake of the fire.

“That fire in Los Alamos, part of my ranch burned, up in the mountains. And then after that, when the monsoon rains comes, after those floods come, it takes all that flow and goes down, down to Santa Fe, down to Santa Clara Pueblo, all those places. That's contaminating a lot.”

The Las Conchas fire burned 150,000 acres. At the time, it was the largest wildfire in New Mexico history. Los Alamos was evacuated, but spared. Santa Clara Pueblo, however, saw 16,000 acres burned, including 45 percent of its watershed1213.

As recently as 2022, the Cerro Pelado fire burned 45,000 acres southwest of the Pajarito Plateau, but didn’t immediately threaten the laboratory. It was the third fire in 2022 caused by a controlled burn gone wrong14.

All of these outcomes are horrific enough as they are. Can you even imagine the outcome if a fire as vicious and uncontrollable as the Eaton Fire—that destroyed Atladena outside Los Angeles in early 2025—swept through a nuclear weapons production facility that also serves as de the facto storage site for more than eight decades of high-level nuclear weapons waste?

We’ve all seen how far wildfire smoke can travel. And fires are getting exponentially worse. Why does a facility like this even exist?

What if Los Alamos National Laboratory’s almost 17,000 employees were actually working on climate change, or properly remediating the Pajarito Plateau? That would be a future worth investing in.

After the Las Conchas fire nearly burned Los Alamos National Laboratory to the ground, Nina Elder made her way up the Pajarito Plateau.

“There was all this standing charcoal. It's not just burnt trees, it's actual charcoal, because it was burning so hot that the oxygen was deprived from the flames. The trees stood in place, incinerated, and turned into pure carbon. I went into those burn areas pretty quickly afterwards and I was collecting that charcoal.”

We were talking about her series of drawings of classified photographs titled, simply, Nuclear, which include painstakingly faithful renderings of, among other things, the Trinity bomb atop its detonation tower; an in-progress intercontinental ballistic missile silo; and the Sedan detonation crater at the Nevada Test Site. Nina draws these using radioactive charcoal harvested from the Los Alamos burn scar.

Nina’s interest in Los Alamos National Laboratory results from a pretty wild personal connection to its history.

“Growing up, part of my childhood was spending summers in the Pecos Mountains. And I knew that my family's property there was handed down through generations, due to a dude ranch being there that was called Mountain View Ranch.

It was started in the late 1800s and continued into the 1960s. My uncles and their dads and their dads were the cowboys associated with that. It was a real cattle ranch, and then it became a dude ranch, as so many of them did.”

There was a cabin up above her family’s that everyone called “Oppenheimer’s Cabin.” In her twenties, Nina started reading book after book about New Mexico’s history.

“I realized that the dude ranch that Oppenheimer went to when he was a child, to deal with his weak lungs and, as some of the texts refer to, his effeminate constitution, he was sent to this dude ranch in New Mexico to toughen up, and that was to hang out with my great-uncle, actually, who was the head of trails and horses at that time.

My great-uncle, who was a very young man, was taking Oppenheimer out on these trail rides all over in between the Pecos Valley, all the way up over the Santa Fe ridges and down to the other side, which is what we now know as Los Alamos. So, when tasked with the Manhattan Project, Oppenheimer remembered these gracious cowboys who could, you know, talk the hooves off a horse, as some people would say. They had the gift of gab.

He remembered this mesa that they had gone to on horseback, where there was just a single ridge of sandstone that went up to it. And then there was this large expansive area on top. He went back and found my great-uncle, who was still his same age, or a little bit older than him, and tasked him to leave the dude ranch and to help build Los Alamos.

And so all of the stories that don't get told about the boys’ school closing, and the Hispanic farmers, as they get labeled in the history books, being pushed off their land, that was a collaboration between my family, Oppenheimer, and the federal government.”

I asked Nina about the process of making those drawings with radioactive charcoal, and how it connected to how she thinks about her family’s history.

“The first of those drawings took me nine months to make. They are meticulous because, I thought, if I am exhausted and annoyed by working on a drawing for nine months, think about the half-life of some of these elements. I can't bemoan nine months of my life.”

You’ll recall that the half-life of plutonium, which is all over the Tularosa Basin as a result of the Trinity detonation in 1945, is 24,000 years.

“Drawing started to take on a kind of, not only reverence but, penance. A lot of people have asked me, ‘Why are the first drawings you ever made ridiculously realistic, and maybe even a little bit overworked, from an artistic point of view?’

I think I felt a very personal responsibility, a very personal connection. I was afraid to not hold myself to the most rigorous standard. But then, at the same time, using this radioactive charcoal, I did not protect myself from it at all, which terrifies people.

There's this sense, I think, when you think about toxic materials, that whoever is using them is wearing these thick rubberized gloves, or a respirator.

But for me, it was a point of entry and interest that so many people in the state of New Mexico were never given the choice to protect themselves—that they are farming, growing food, living in places that they culturally and personally would never leave. They don't have a choice. So, what does it mean for me to be able to flit in and out of that? To expose myself for nine months, or four years, or however long I'm working on something, and then to remove myself from that?

And it's really problematic. It's really challenging. And this was half my lifetime ago, when I was making those drawings. It’s really interesting to think about that decision, as an artist: exposure as a point of protest.”

There are echoes here from our previous installment Wastelanding (Part 02), when First Nation artist Bonnie Devine placed a small piece of uranium into a university exhibition space in Toronto, prompting administrators to panic about exposure.

“In the years since then, what I’ve seen is that they get shown a lot. These are popular drawings. They’ll be hanging in a museum and people will walk up to them–they’re really detailed—they’ll get their nose just inches from the drawing. They’ll be really examining it. That’s part of the joy of really detailed art, is that people come up to it. And then they look at the materials list, and they see that it’s made out of radioactive charcoal. The first thing that happens is that they become afraid for themselves. People back away from the drawings, with their bodies.”

Just to be clear, when exhibited, Nina’s drawings are secured inside of specific frames with special glass that protects viewers from radiation exposure.

“But then I’m hoping for two more things. I know that the next step is that they become afraid for me, as the artist. They think about, wow, a human hand drew this. A human face spent hours very close to this drawing, breathing this in. So their next step is to become concerned for me.

I want them to take the next step and become concerned for the people who are living in that reality. So, creating momentary experiences of exposure—and maybe little tiny trauma responses in an audience—is something I use incredibly intentionally. Because I think we should be having a very large, long-term response to the exposures that those moments caused.”

These types of recognitions rhyme with those that Joseph Masco attempts to articulate through his concept of the nuclear uncanny.

“The theoretical frame for the uncanny comes from psychoanalysis. And it has to do with a moment where you have a recognition of mis-recognition. There's a moment where, whatever you're perceiving, you understand something is wrong with it.

And then it has, from Freud’s point of view, a kind of circuit of something you already know being made strange, and coming back to you, in a way. I remade that concept, via the nuclear uncanny, to talk about what people are experiencing and understanding when they’re trying to talk about the nuclear age, writ large, and nuclear national security, in particular.

Around a place like Los Alamos, it's super complicated because you have a weapons facility on top of a mountain that is a spiritual home to dozens of Indigenous communities that have been there for thousands of years, in some cases.

But you also have neighboring villages that are the descendants of Spanish and Mexican colonists in the region that go back 400 or 500 years, in some cases. And then you have communities that are built out mostly through Anglo and white immigration, often that are really foundational to a kind of antinuclear movement in the area.

When you have that kind of diversity of perspective, the nuclear uncanny is a really interesting frame for eliciting out people who have experienced in their own lives nuclear fear, nuclear security, nuclear technologies, but also to really foundationally anchor the idea that this is not a single formation. You've got communities that have really different ideas of what nature is, really different ideas about what futurity is, really different ideas about what security might look like.

And really importantly in the case of northern New Mexico, from the Manhattan Project from 1942 onwards to today really different experiences of cities, citizenship and questions of race and gender and class within those frames.”

In 2024, artist Rose B Simpson, who is from Santa Clara Pueblo, was included in the Whitney Biennial. This large-scale survey exhibition is staged every two years with the charge of taking the pulse of contemporary American art.

At the Whitney, Rose showed a collection of four larger-than-life ceramic figures, titled Daughters. Organized in a circle, and each of slightly different earthen colors, they were exemplary of Rose’s signature processes. Here handprints were visible on their surfaces, and each was adorned with glyph-like markings and unique accouterments.

In addition to her ceramics practice, I should also mention that Rose built an incredibly sick car. She named it Maria.

“Maria is a 1985 Chevy El Camino that is built as a street rod. She has a 410 horsepower, 350 drag race transmission, and she is painted like our traditional black on black wear from Tewa Pueblos of northern New Mexico.”

Maria is a nod to renowned San Ildefonso ceramic artist Maria Martinez (1887-1980) who, along with her husband Julian, developed an innovative way to produce matte-black designs over polished-black ceramic surfaces.

One of the main arteries up to Los Alamos was built alongside Santa Clara Pueblo, and lab traffic passes by every morning and every evening. I asked Rose what it was like to grow up in such close proximity to Los Alamos National Laboratory.

“I had people in my family who all sustain themselves through work at the lab. And then also, growing up a Pueblo, bombs would go off all the time. The windows shake, the trees sometimes would bend. You'd be playing in the sandbox, or out riding bikes, and the bomb would go off. You’d kind of turn to that direction and then go on with your day. I remember being a kid and being deeply aware of the existential dread of nuclear bombs.

My thesis show from undergrad was based on the fact that I had cancer at 18 years-old, and I believe that that was directly because of growing up downstream from the lab. The fact that I was told I couldn't have kids was because of being downstream from the lab. And the amount of cancers in the area, deformities in animals, and so on.

It was really, really close to home. I had this freak cancer situation at 18. So, it’s definitely a very core part of that awareness of apocalypse and the tenuousness of our humanity itself.

I had been really interested in post-apocalyptic theory for a really long time, because I'm a Native person who has experienced the postcolonial stress disorder world, where we are living in that experience of apocalypse, in lots of ways.”

Rose’s four-part work in the Whitney Biennial, I wrote at the time, nodded to the four earthly elements, cardinal directions, or seasons. And designated as “daughters,” I think they pointed to multilinear conceptions of time. They look forward into the future, far past the apocalypse, while simultaneously referencing Rose’s own matrilineage:

“My mom is an artist and has a nonprofit organization that studies permaculture.”

Rose’s mom is Roxanne Swentzell, the ceramic artist I wrote those papers about in undergrad, who has that studio and gallery in Pojoaque. And Rose’s grandmother was the late architect, historian, and activist Rina Swentzell.

“A lot of my work is about why we do what we do, what makes us human. How do we become self-aware enough that we make good decisions? How do I become self-aware enough that I can be sensitive enough to understand the implications of what I’m doing to the world so that I don’t actively contribute—or passively contribute—to the demise of what I love about humanity?

When I was young in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, I always believed that the world was going to end the year 2000. I was superbly aware of the environmental catastrophe that we're experiencing, and that there was going to inevitably be some sort of ending. And in that ending there had to be an innovative recreation of reality.

I was really obsessed with this idea that there is a world after. I was always studying movies and books. Cormac McCarthy, and Book of Eli, Mad Max, Waterworld. All these theories of what it looks like right after the apocalypse and how people navigate the post-ending.

In a sense, it's like looking forward to the apocalypse of colonialism.”

Los Alamos National Laboratory puts forward a great deal of effort to brand itself as more than just a nuclear weapons factory. The lab boasts about innovative work in the fields of climate science, space exploration, artificial intelligence, and genetics.

Staff numbers have swelled in recent years, from around 13,000 in 2020, to an almost 17,000-person payroll in 202415 (and more than 18,000, if you count contractors). This year, they’re likely to hit 20,000 employees16.

And I’m actually inclined to give a lot of the people who work there the benefit of the doubt, even if the hiring trends (and radically increased budget17) are directly related to increased plutonium pit production goals.

I don’t think the employees of Los Alamos are evil, necessarily. People make their way up the hill for a variety of reasons. Maybe it’s only the socioeconomic stepladder that’s available near their families. Maybe they think the exploration of Mars is a noble pursuit. Maybe they hope that their interests in robotics could help hospitals perform safer surgeries, or that their research into environmental science might curb a warming planet, or even clean up the canyons around the lab.

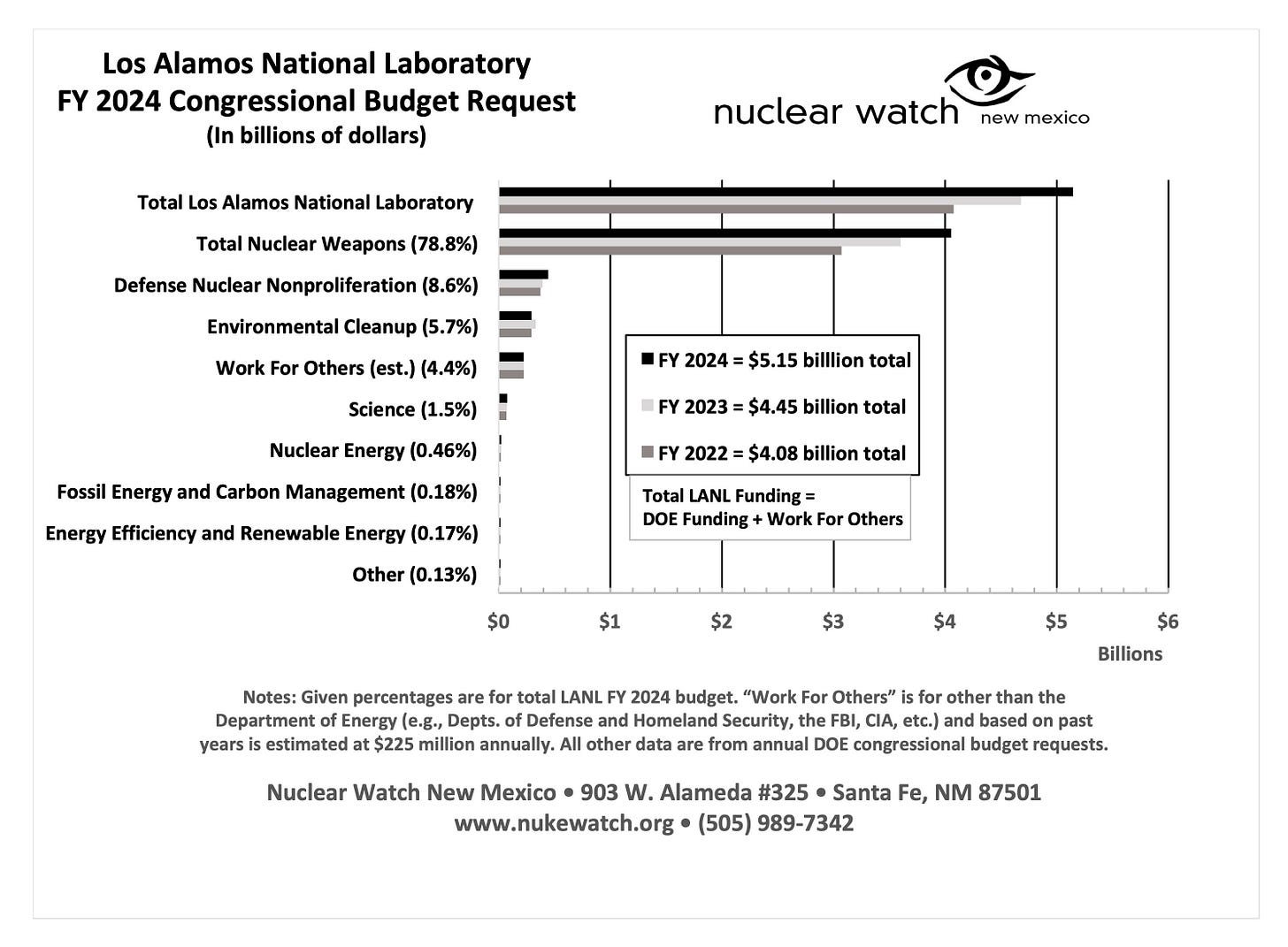

Unfortunately, environmental cleanup is only about 5.7% of the lab’s budget—and that is, relatively speaking, on the high-end of non-weapons work.

When I met up with Joni Arends, she brought along a copy of the lab’s 2024 Congressional Budget Request, which was published by Nuclear Watch New Mexico. Lab employees love to talk about the Mars Rover, but “Science” work, which presumably includes space exploration and the genetics, is 1.5%. Nuclear energy is less than 0.5%. Renewables are 0.17%18.

So what does the lab spend its money on? Of the $5.15 billion in Congressional funding for 2024, 78.8%—over $4 billion—was earmarked for nuclear weapons production19.

Los Alamos National Laboratory, as an institution, as an extension of the nuclear nationalist empire of the United States of America, has essentially zero interest in human, planetary, or interplanetary health.

It is, fundamentally, an 8.4-million-square-foot Armageddon Factory, funded out of your paycheck.

In 2009, the Center for Land Use Interpretation hosted an alternative bus tour that visited Los Alamos20. I wasn’t in attendance, but CLUI director Matthew Coolidge filled me in on the scope, when we spoke over video call in August 2024.

“One of the things of this Land of Enchantment, is this idea of the resonating energies of the sun, yes? But also of the fake sun, the new sun, the atomic sun.

If you look at the point of origin for postwar consumerism, globally, originating with the atomic test of Trinity, it becomes a sort of Big Bang, if you want to go down that road, and then the Conradian source of it all is Los Alamos National Laboratory.

That's where the Druids up on the Hill Station constructed the mechanism that changed the world and engaged in, arguably, the first technology on that scale that is truly sort of irreversible. Though, of course, climate change, carbon, is certainly part of that argument as well. But just in terms of the single mechanism, and it coming down to just a handful of individuals up there in the lab…

So we were looking at it in that sort of Joseph Conrad way. And I suppose going up to the source to see Kurtz, or whatever. We were thinking about Los Alamos as this incredibly innovative engineering center, but also the origin of this zero point in the zero time of of the beginning of the nuclear age.”

If you’ve enjoyed Time Zero and want to support my research, you can subscribe below (or upgrade to a paid subscription).

If there’s anyone you think might be interested in Time Zero, please share.

“Avanyu Trail Day.” Museum of Indian Arts & Culture. Accessed 07 July 2024.

Oak Ridge Associated Universities. “Trinitite.” Museum of Radiation and Radioactivity.

Newman, Brent D. “The Hydrogeology of Los Alamos National Laboratory: Site History and Overview of Vadose Zone and Groundwater Issues.” Vadose Zone Journal, August 2005.

Carrillo, Charlie M and Filipe R Mirabal. “The Mystery of the Penitentes.” El Palacio. Winter 2019.

Traverso, Sol. “A glimpse inside the private world of Los Hermanos Penitentes.” Taos News. 7 April 2022.

Office of Scientific and Technical Information. “Plutonium Chemistry and Metallurgy.” The Manhattan Project: An Interactive History.

Dummer, JE with JC Taschner and CC Courtright. “The Bayo Canyon/radioactive lanthanum (RaLa) program.” Office of Scientific & Technical Information Technical Reports. April 1996.

Boughzala, K and E Ben Salem, A Ben Chrifa, E Gaudin, and K Bouzouita. “Synthesis and characterization of strontium–lanthanum apatites.” Materials Research Bulletin. Volume 42, Issue 7. 3 July 2007.

“Santa Clara Watershed Assessment Study.“ US Army Corps of Engineers.

Todd, Jeff. “Pueblo needs help, prepares for rain.” KRQE. 08 July 2011.

Wyland, Scott. “Forest Service report finds Cerro Pelado Fire sparked by agency prescribed burn.” Santa Fe New Mexican. 24 July 2023.

LANL News Release. “Los Alamos National Lab Announces 10 Milestones Of Community Connection In 2023.” The Los Alamos Reporter. 22 December 2023.

Rael, Zach. “Los Alamos National Lab announces plans to hire up to 1,000 workers.” KOB4. 31 July 2025.

Wyland, Scott. “Los Alamos National Lab's budget could grow to a record $5 billion in next fiscal year.” 12 March 2024.

“Los Alamos National Laboratory FY 2024 Congressional Budget Request.” Nuclear Watch New Mexico. PDF. June 2023.

Ibid.

”CLUI Leads Tour of New Mexico.” Center for Land Use Interpretation. Spring 2010.